Fungal spores sketch out minute air currents in this shortlisted photograph by Avilash Ghosh. The moth atop a mushroom appears to admire the celestial view. In the largely still air near the forest floor, mushrooms use evaporation and buoyancy to generate air flows capable of lifting their spores high enough to catch a stray breeze. (Image credit: A. Ghosh/CUPOTY; via Colossal)

Tag: flow visualization

“Lively”

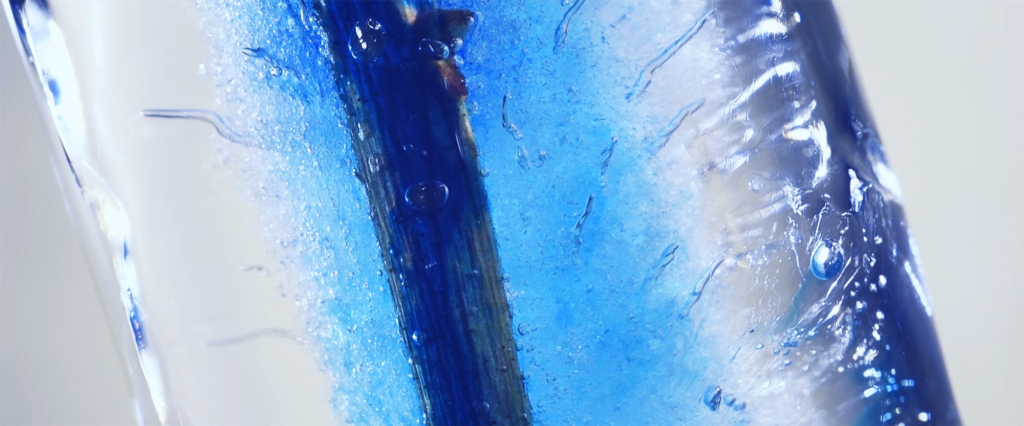

In “Lively,” filmmaker Christopher Dormoy zooms in on ice. He shows ice forming and melting, capturing bubbles and their trails, as well as the subtle flows that go on in and around the ice. By introducing blue dye, he highlights some of the internal flows we would otherwise miss. (Video and image credit: C. Dormoy)

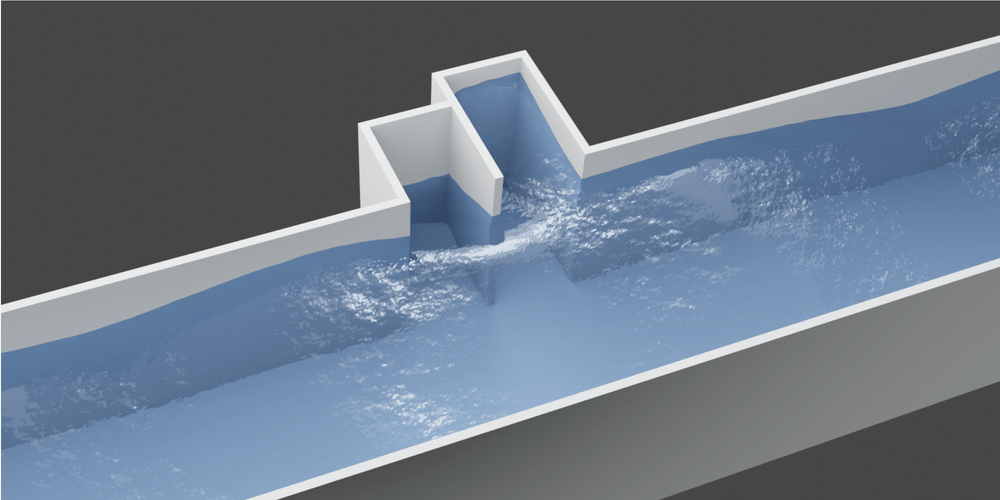

How CO2 Gets Into the Ocean

Our oceans absorb large amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Liquid water is quite good at dissolving carbon dioxide gas, which is why we have seltzer, beer, sodas, and other carbonated drinks. The larger the surface area between the atmosphere and the ocean, the more quickly carbon dioxide gets dissolved. So breaking waves — which trap lots of bubbles — are a major factor in this carbon exchange.

This video shows off numerical simulations exploring how breaking waves and bubbly turbulence affect carbon getting into the ocean. The visualizations are gorgeous, and you can follow the problem from the large-scale (breaking waves) all the way down to the smallest scales (bubbles coalescing). (Video and image credit: S. Pirozzoli et al.)

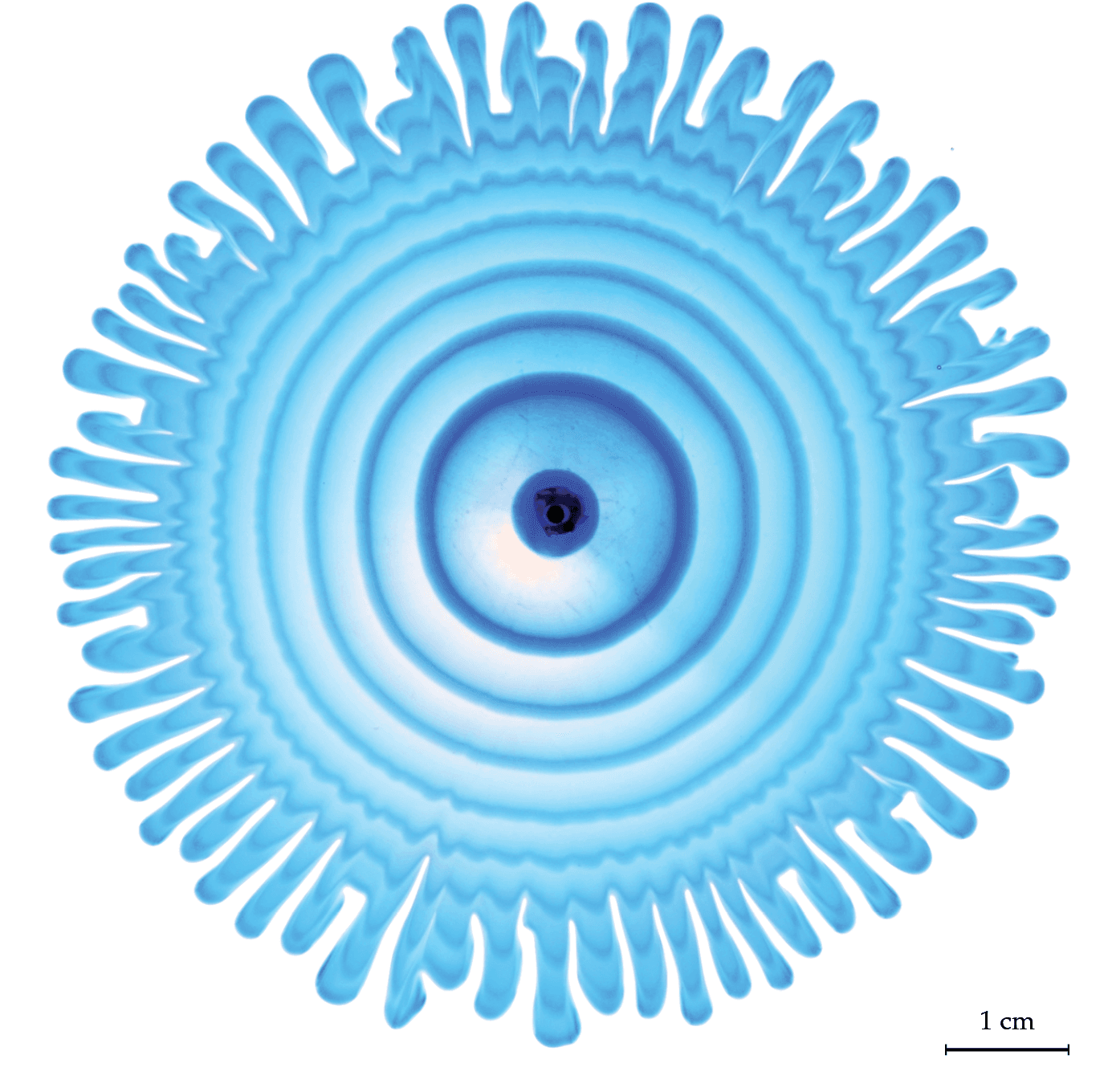

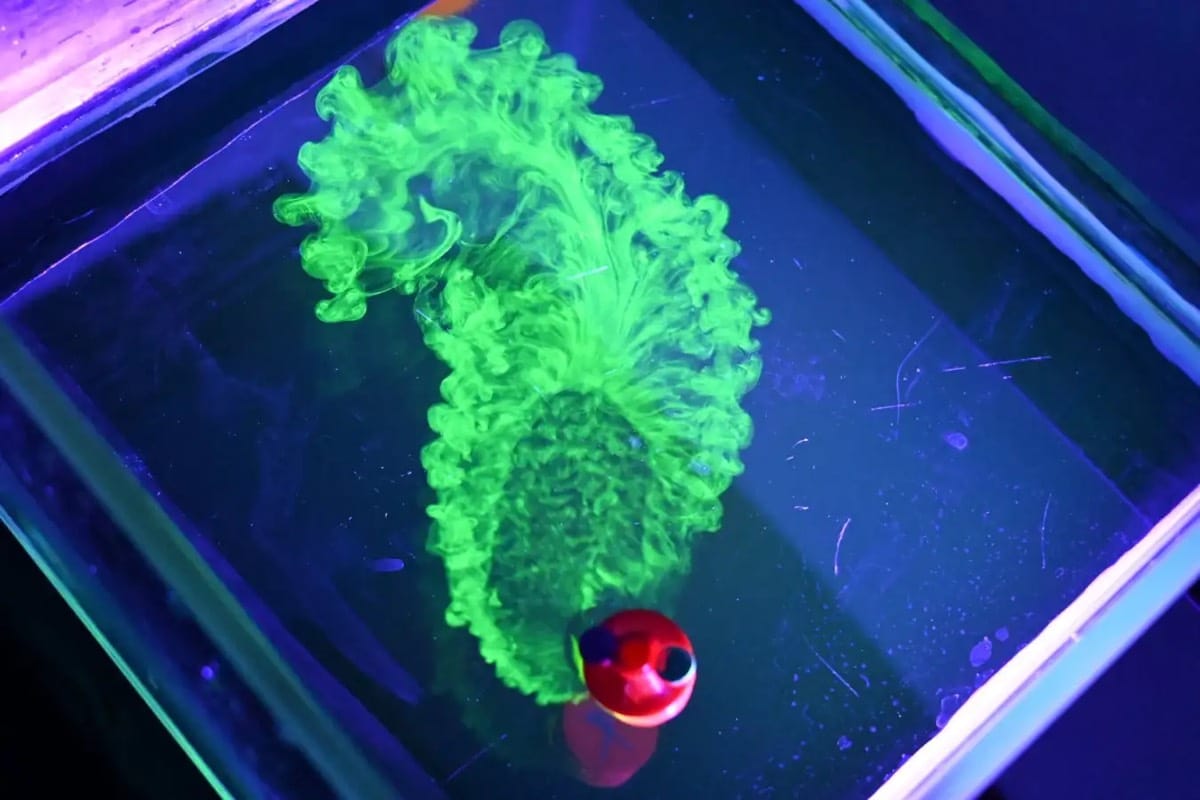

Flow Behind Viscous Fingers

Nature is full of branching patterns: trees, lighting, rivers, and more. In fluid dynamics, our prototypical branching pattern is the Saffman-Taylor instability, created when a less viscous fluid is injected into a more viscous one in an confined space. Most attention in this problem has gone to the branching interface where the two fluids meet, but recently, a team has examined the flow away from the fingers by alternately injecting dyed and undyed fluid to visualize what goes on. That’s what we see here. Notice how the central dye rings, far from the branching fingers, still appear circular. Yet, even a few centimeters away from the fingers, the dye is starting to show ripples that correspond to the fingers. That’s an indication that the pressure gradient generated at the tips of the fingers is pretty far-reaching! (Image and research credit: S. Gowen et al.)

The Mystery of the Binary Droplet

What goes on inside an evaporating droplet made up of more than one fluid? This is a perennially fascinating question with lots of permutations. In this one, researchers observed water-poor spots forming around the edges of an evaporating drop, almost as if the two chemicals within the drop are physically separating from one another (scientifically speaking, “undergoing phase separation“). To find out if this was really the case, they put particles into the drop and observed their behavior as the drop evaporated. What they found is that this is a flow behavior, not a phase one. The high concentration of hexanediol near the edge of the drop changes the value of surface tension between the center and edge of the drop. And that change is non-monotonic, meaning that there’s a minimum in the surface tension partway along the drop’s radius. That surface tension minimum is what creates the separated regions of flow. (Video and image credit: P. Dekker et al.; research pre-print: C. Diddens et al.)

Within a Drop

In this macro video, various chemical reactions swirl inside a single dangling droplet. Despite its tiny size, quite a lot can go on in a drop like this. Both the injection of chemicals and the chemical reactions themselves can cause the flows we see here. Surface tension variations and capillary waves on the exterior of the drop can play a role, too. Just because a flow is tiny doesn’t mean it’s simple. (Video and image credit: B. Pleyer; via Nikon Small World in Motion)

Chemical reactions swirl within a single, hanging droplet.

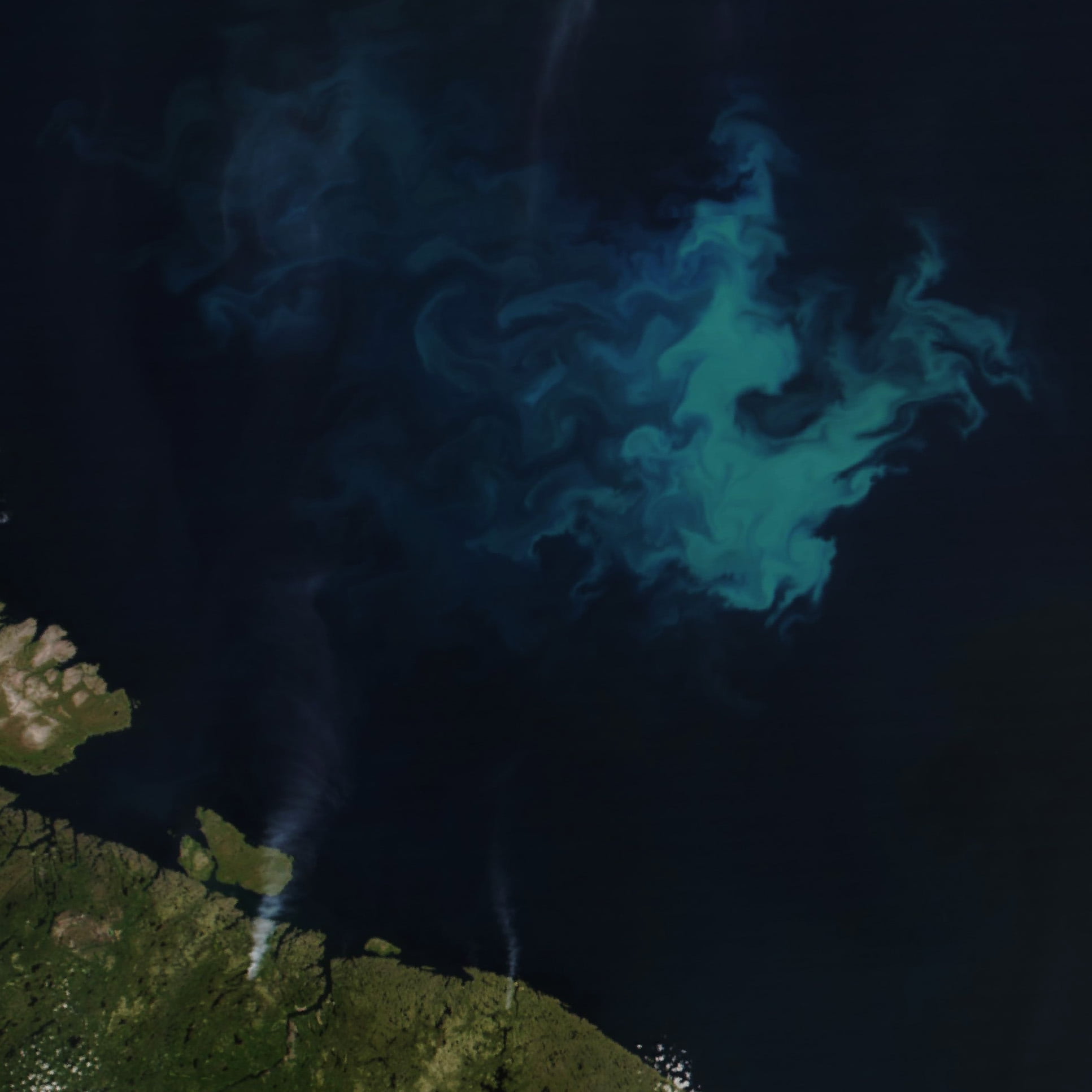

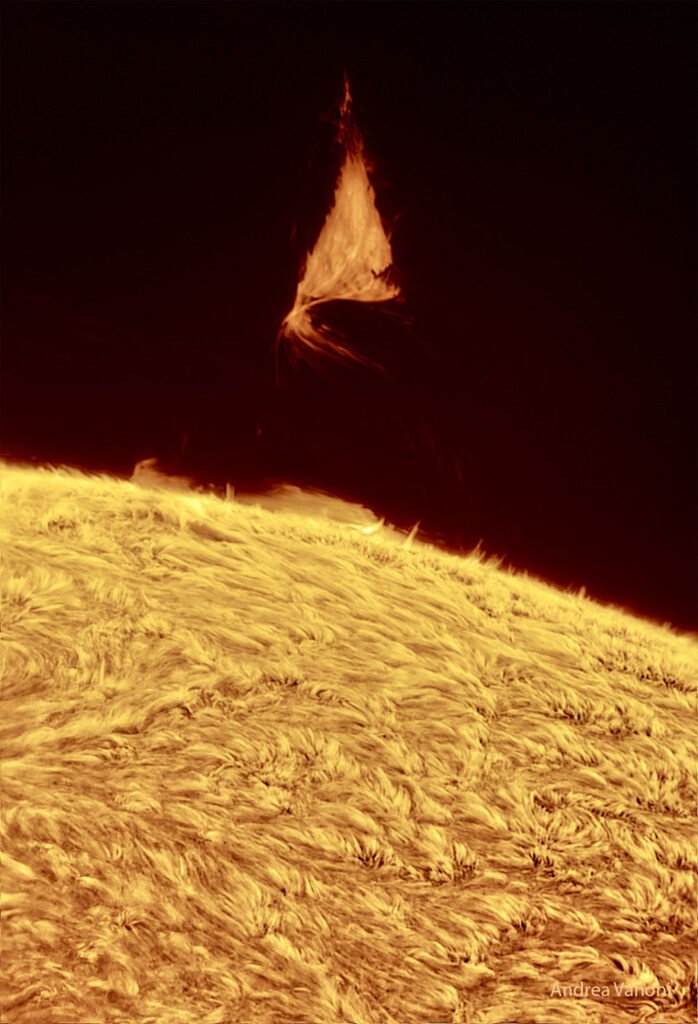

Blooming in Blue

Summers in the Barents Sea — a shallow region off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia — trigger phytoplankton blooms like the one in this satellite image. The blue shade of the bloom suggests the work of coccolithophores, a type of plankton armored in white calcium carbonate. This type of plankton thrives in the warm, stratified waters of the late summer. Earlier in the year, the water tends to be nutrient-rich and well-mixed, conditions which favor diatom plankton species instead. Their blooms appear greener in satellite images. (Image credit: W. Liang; via NASA Earth Observatory)

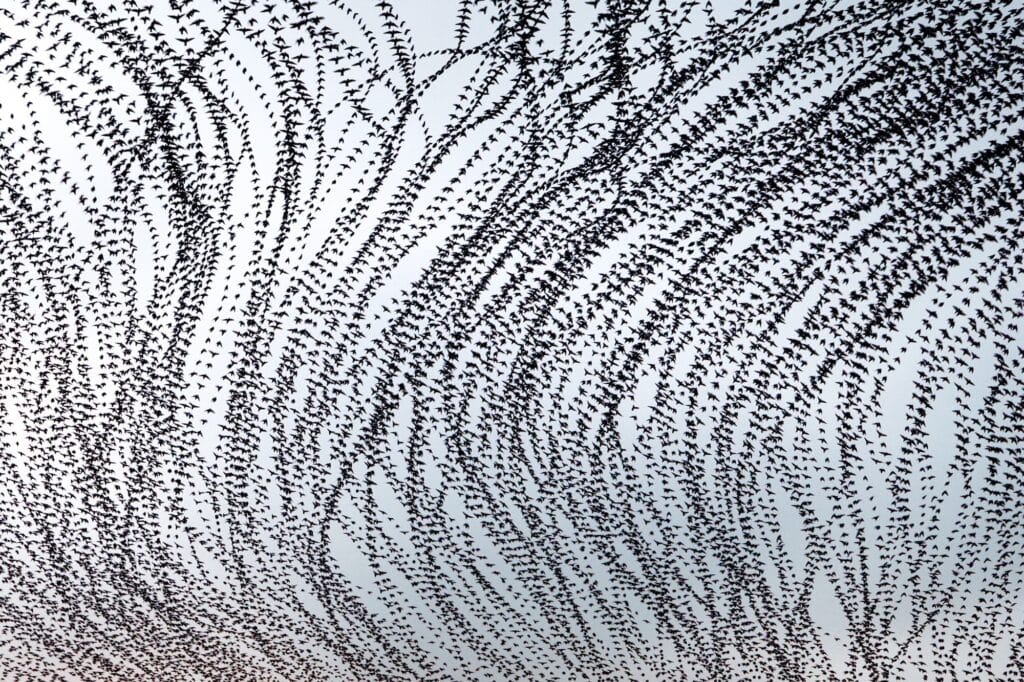

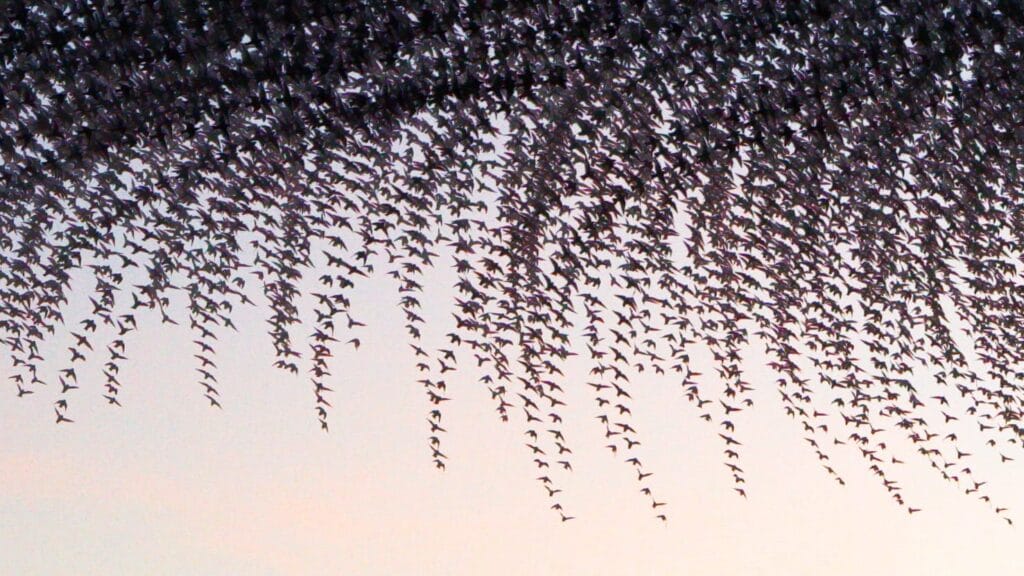

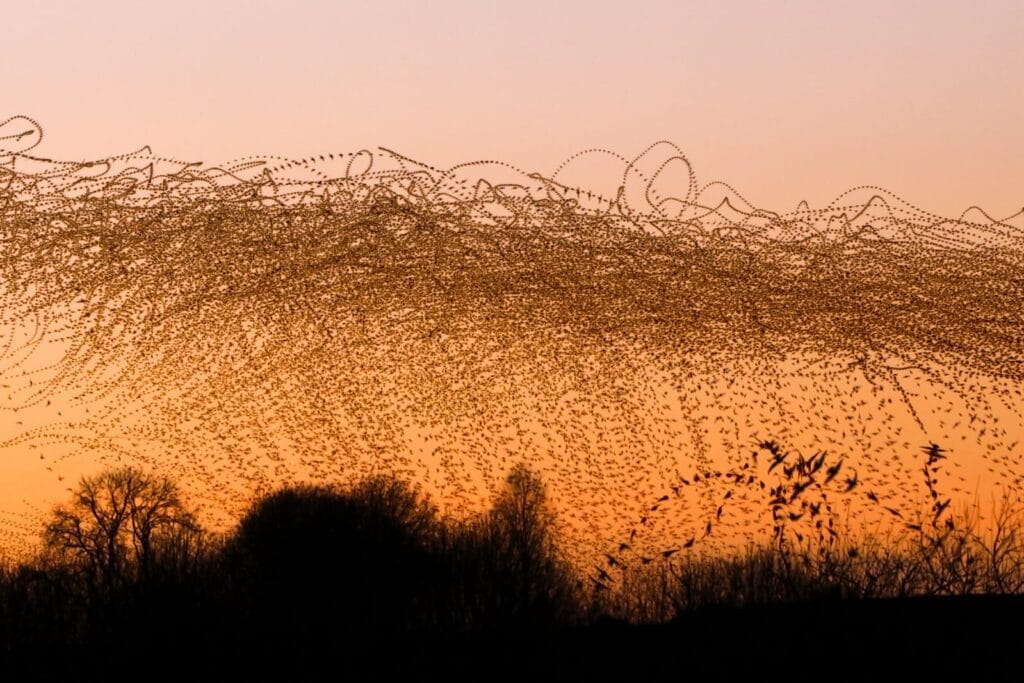

Strata of Starlings

Starlings come together in groups of up to thousands of birds for the protection of numbers. These flocks form spellbinding, undulating masses known as murmurations, where the movement of individual starlings sends waves spreading from neighbor to neighbor through the group. One bird’s effort to dodge a hawk triggers a giant, spreading ripple in the flock.

To capture the flowing nature of the murmuration, photographer and scientist Kathryn Cooper layers multiple images of the starlings atop one another. The birds themselves become pathlines marking the murmuration’s motion. The final images are surprisingly varied in form. Some flocks resemble a downpour of rain; others the dangling branches of a tree. (Image credit: K. Cooper; via Colossal)

Active Cheerios Self-Propel

The interface where air and water meet is a special world of surface-tension-mediated interactions. Cereal lovers are well-aware of the Cheerios effect, where lightweight O’s tend to attract one another, courtesy of their matching menisci. And those who have played with soap boats know that a gradient in surface tension causes flow. Today’s pre-print study combines these two effects to create self-propelling particle assemblies.

The team 3D-printed particles that are a couple centimeters across and resemble a cone stuck atop a hockey puck. The lower disk area is hollow, trapping air to make the particle buoyant. The cone serves as a fuel tank, which the researchers filled with ethanol (and, in some cases, some fluorescent dye to visualize the flow). Like soap, ethanol’s lower surface tension disrupts the water’s interface and triggers a flow that pulls the particle toward areas with higher surface tension. But, unlike soap, ethanol evaporates, effectively restoring the interface’s higher surface tension over time.

With multiple self-propelling particles on the interface, the researchers observed a rich series of interactions. Without their fuel, the Cheerios effect attracted particles to each other. But with ethanol slowly leaking out their sides, the particles repelled each other. As the ethanol ran out and evaporated, the particles would again attract. By tweaking the number and position of fuel outlets on a particle, the researchers found they could tune the particles’ attractions and motility. In addition to helping robots move and organize, their findings also make for a fun educational project. There’s a lot of room for students to play with different 3D-printed designs and fuel concentrations to make their own self-propelled particles. (Research and image credit: J. Wilt et al.; via Ars Technica)