Like so many other performers, the singers and musicians of New York’s Metropolitan Opera House were left without a way to safely perform when the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic began in early 2020. In search of safe ways to perform and rehearse, the Met turned to researchers at nearby Princeton University, who worked directly with the performers to explore aerosol production and airflow in the context of professional opera.

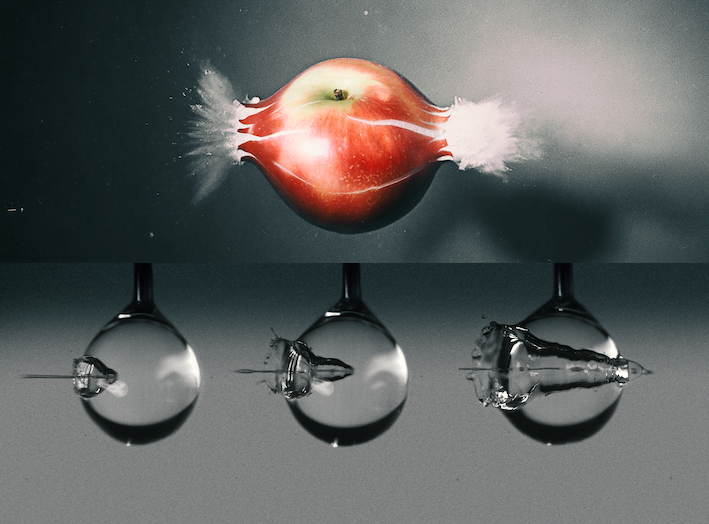

Through visualization and other experiments, the team found that the highly-controlled breathing of opera singers actually posed a lower risk for spreading pathogens than typical speaking and breathing. Most of a singer’s voiced sounds are sustained vowels, which produce a slow, buoyant jet that remains close to a singer. The exception are consonants, which created rapid, forward-projected jets.

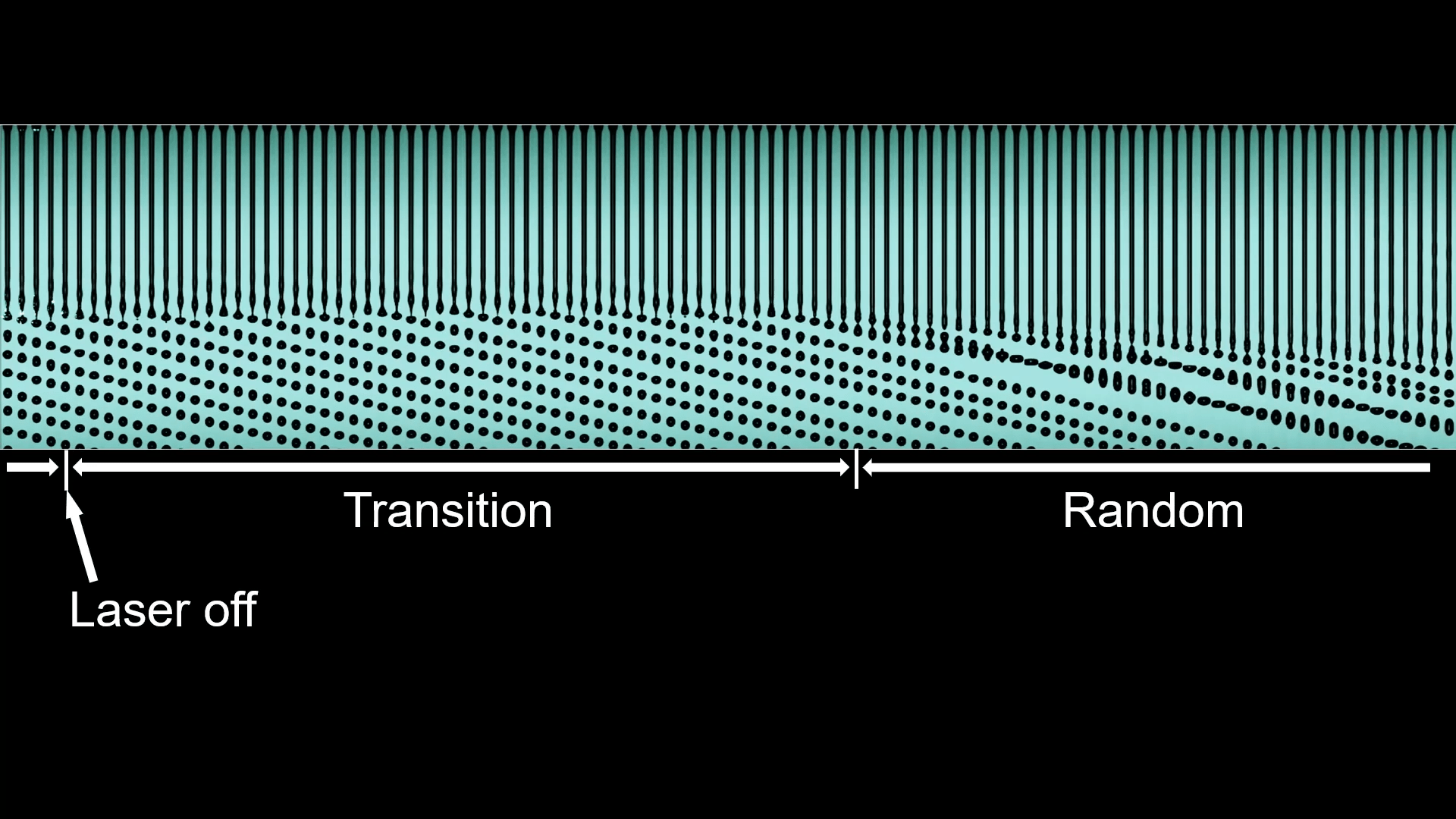

In the orchestra, the researchers found that placing a mask over the bell of wind instruments like the trombone reduced the speed and spread of air. One of the highest risk instruments they found was the oboe. Playing the oboe requires a long, slow release of air, but between musical phrases, oboists rapidly exhale any remaining air from their lungs and take a fresh breath. That rapid exhale creates a fast, forceful jet of air that necessitates placing the oboist further from others. (Image credit: top – P. Chiabrando, others – P. Bourrianne et al.; research credit: P. Bourrianne et al.; via APS Physics; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)