Happy 2026! This will be a big year for me. I’ll be finishing up and turning in the manuscript for my first book — which flows between cutting edge research, scientists’ stories, and the societal impacts of fluid physics. It’s a culmination of 15 years of FYFD, rendered into narrative. I’m so excited to share it with you when it’s published in 2027.

As always, though, we’ll kick off the year with a look back at some of FYFD’s most popular posts of 2025. (You can find previous editions, too, for 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, and 2014.) Without further ado, here they are:

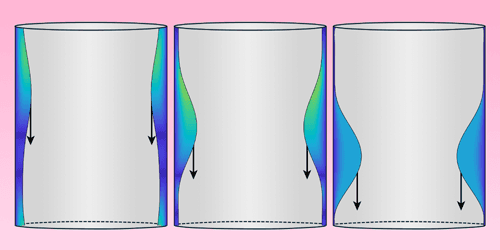

- Charged Drops Don’t Splash

- Strata of Starlings

- Espresso in Slow-Mo

- The Incredible Engineering of the Alhambra

- Uranus Emits More Than Thought1

- Kolmogorov Turbulence

- Bow Shock Instability

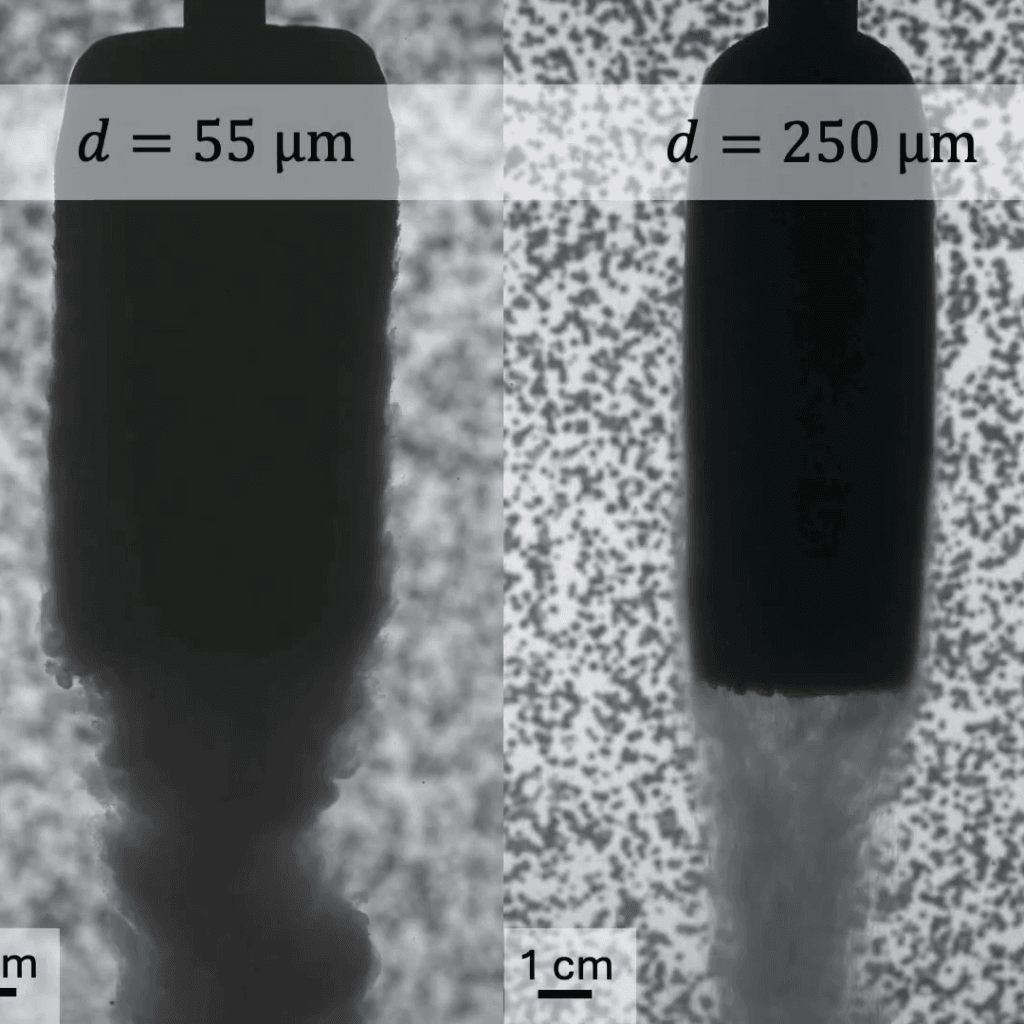

- How Particles Affect Melting Ice

- The Puquios System of Nazca

- Cooling Tower Demolition

- A Glimpse of the Solar Wind

- Bubbling Up

- A Sprite From Orbit

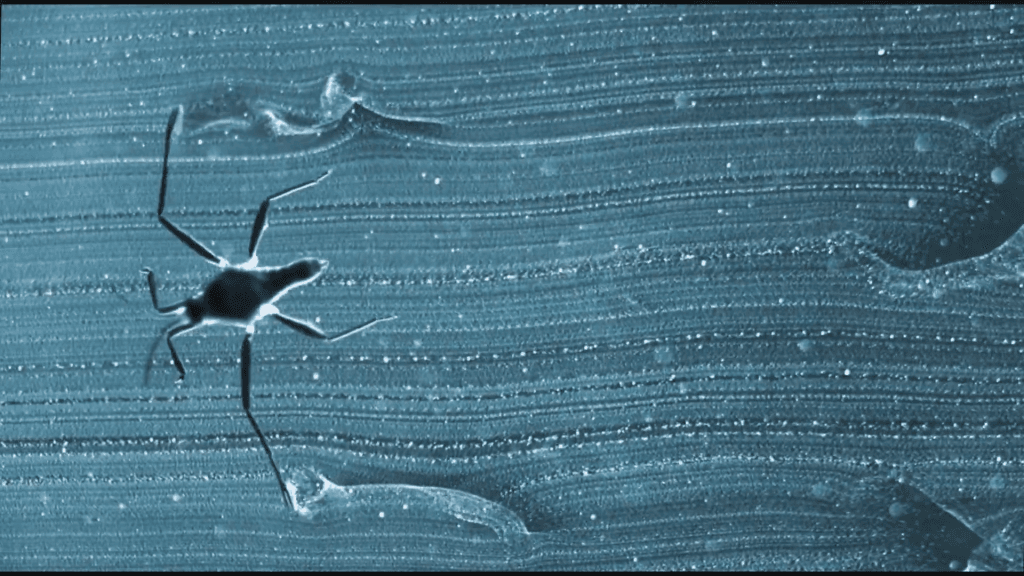

- Cornflower Roots Growing

- How Sunflowers Follow the Sun

What a great bunch of topics! I’m especially happy to see so many research and research-adjacent posts were popular. And a couple of history-related posts; I don’t write those too often, but I love them for showing just how wide-ranging fluid physics can be.

Interested in keeping up with FYFD in 2026? There are lots of ways to follow along so that you don’t miss a post.

And if you enjoy FYFD, please remember that it’s a reader-supported website. I don’t run ads, and it’s been years since my last sponsored post. You can help support the site by becoming a patron, buying some merch, or simply by sharing on social media. And if you find yourself struggling to remember to check the website, remember you can get FYFD in your inbox every two weeks with our newsletter. Happy New Year!

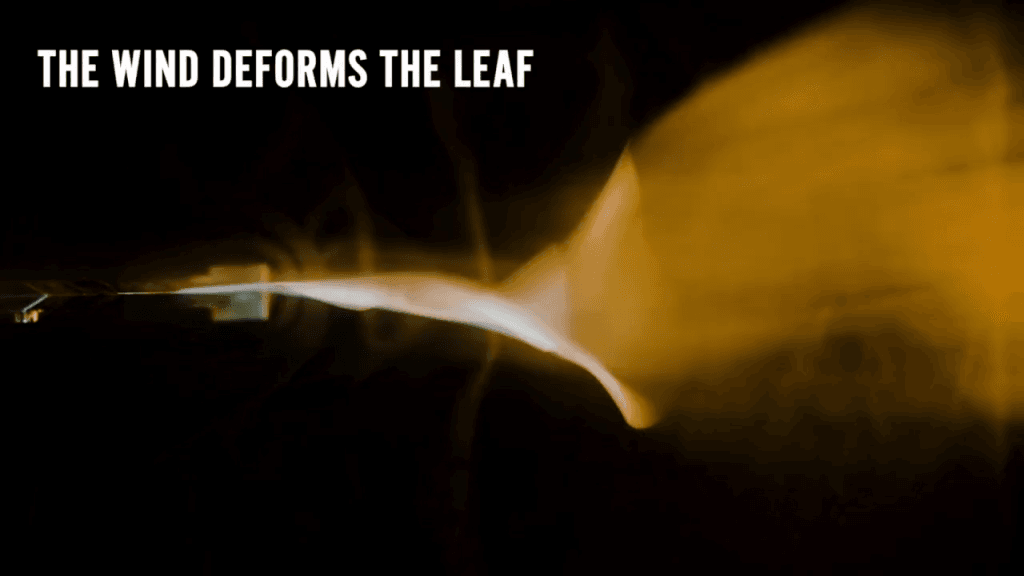

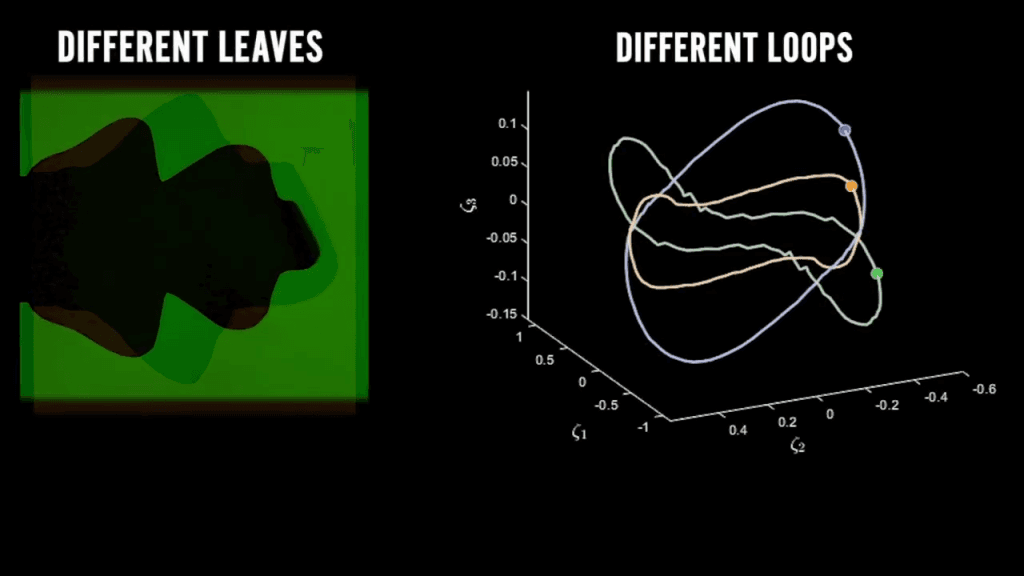

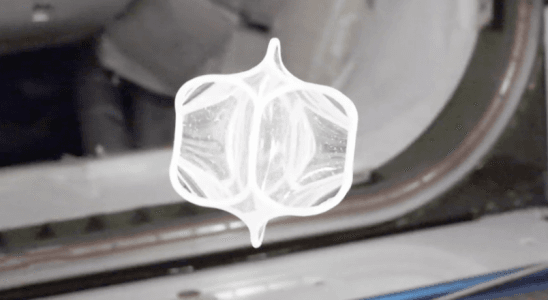

(Image credits: droplet – F. Yu et al., starlings – K. Cooper, espresso – YouTube/skunkay, fountain – Primal Space, Uranus – NASA, turbulence – C. Amores and M. Graham, capsule – A. Álvarez and A. Lozano-Duran, melting ice – S. Bootsma et al., puquios – Wikimedia, cooling towers – BBC, solar wind – NASA/APL/NRL, Lake Baikal – K. Makeeva, sprite – NASA, roots – W. van Egmond, sunflowers – Deep Look)

- I know what I did. ↩︎