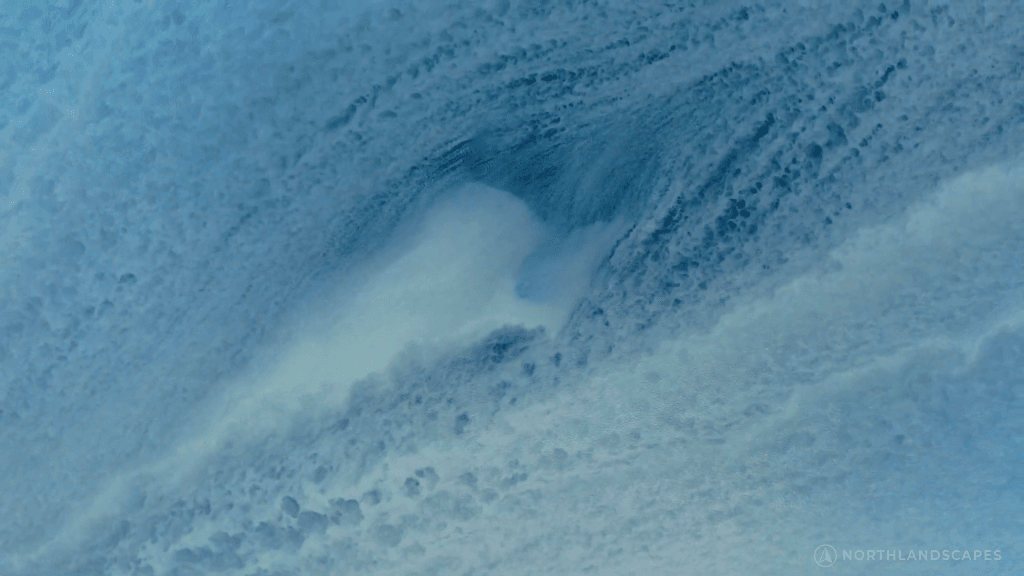

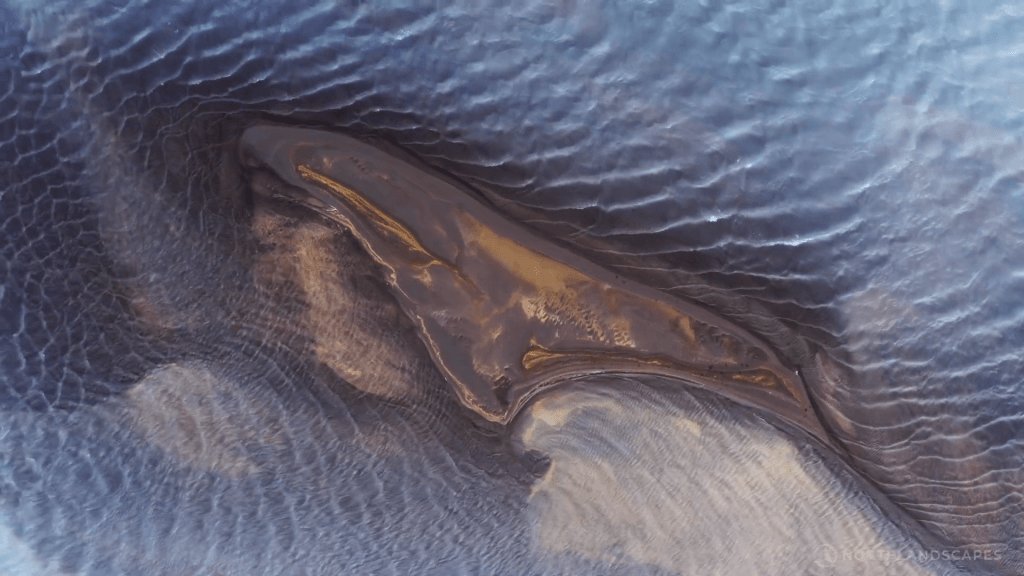

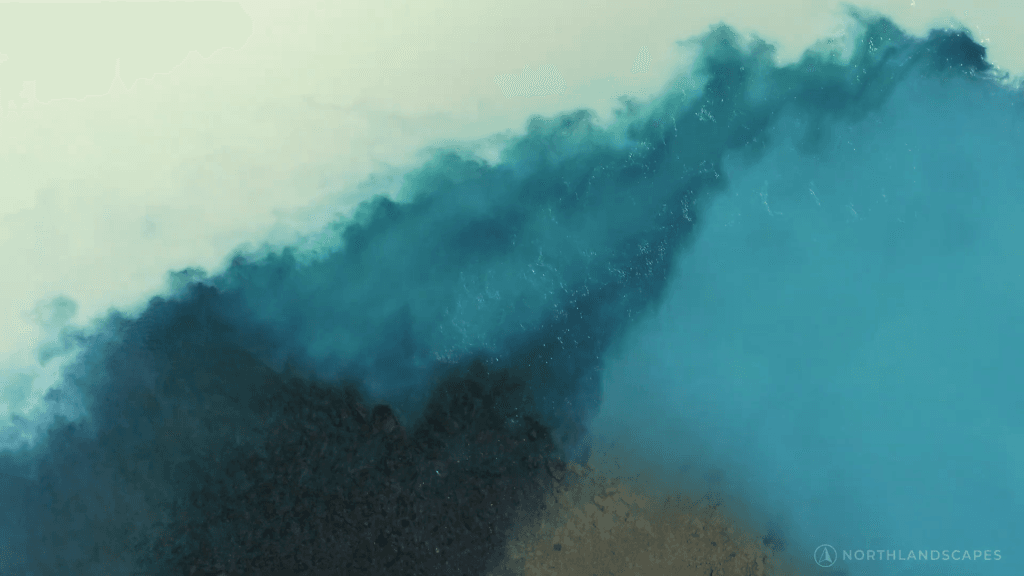

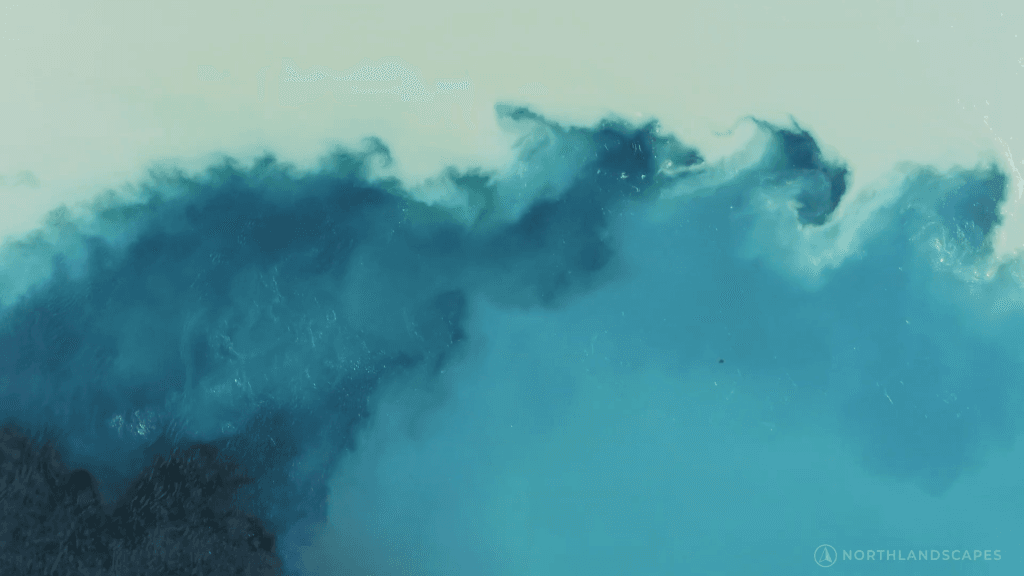

Glacier-fed rivers are often rich in colorful sediments. Here, photographer Jan Erik Waider shows us Iceland’s glacial rivers flowing primarily in shades of blue. While the wave action and diffraction in these videos is great, the real star is the turbulent mixing where turbid and clearer waters meet. Watch those boundaries, and you’ll see shear from flows moving at different speeds which feeds the ragged, Kelvin-Helmholtz-unstable edge between colors. (Video and image credit: J. Waider; via Laughing Squid)

Tag: rivers

A Braided River

The Yarlung Zangbo River winds through Tibet as the world’s highest-altitude major river. Parts of it cut through a canyon deeper than 6,000 meters (three times the depth of the Grand Canyon). And other parts, like this section, are braided, with waterways that shift rapidly from season to season. The swift changes in a braided river’s sandbars come from large amounts of sediment eroded from steep mountains upstream. As that sediment sweeps downstream, some will deposit, which narrows channels and can increase their scouring. The river’s shape quickly becomes a complicated battle between sediment, flow speed, and slope. (Image credit: M. Garrison; animation credit: R. Walter; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Cutting Out Canyons

Over the millennia, the Colorado River has carved some of the deepest and most dramatic canyons on our planet. This astronaut photo shows the river near its dam at Lake Powell. The strip of white edging the lake is the “bathtub ring” that shows how the water level has varied over the years. The deep canyons — over 400 meters from the Horn in the center of the photo to the river beside it — throw shadows across the landscape. To reach these depths, the Colorado River incised its path into bedrock that was tectonically uplifted. (Image credit: NASA; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Capturing River Waves

Rainfall, ice jams, and dam breaks create surges of high flow that make their way down a river in a wave that stretches tens to thousands of kilometers in length. Traditionally, scientists monitor such flow waves using river gauges, which measure river height at specific locations. But gauges are few and far between on many rivers, so a group of researchers are supplementing that data with the SWOT (Surface Water and Ocean Topography) spacecraft. SWOT bounces microwaves off the water to precisely measure the water’s height, giving researchers a glimpse of the flow wave’s shape along the entire river.

In their paper, the team identify and describe flow waves on three different rivers — the Yellowstone, Colorado, and Ocmulgee rivers — ranging in height up to 9 meters and stretching up to 400 kilometers. (Image credit: CNES; research credit: H. Thurman et al.; via Gizmodo)

Bifurcating Waterways

Your typical river has a single water basin and drains along a river or two on its way to the sea. But there are a handful of rivers and lakes that don’t obey our usual expectations. Some rivers flow in two directions. Some lakes have multiple outlets, each to a separate water basin. That means that water from a single lake can wind up in two entirely different bodies of water.

The most famous example of these odd waterways is South America’s Casiquiare River, seen running north to south in the image above. This navigable river connects the Orinoco River (flowing east to west in this image) with the Rio Negro (not pictured). Since the Rio Negro eventually joins the Amazon, the Casiquiare River’s meandering, nearly-flat course connects the continent’s two largest basins: the Orinoco and the Amazon.

For more strange waterways across the Americas, check out this review paper, which describes a total of 9 such hydrological head-scratchers. (Image credit: Coordenação-Geral de Observação da Terra/INPE; research credit: R. Sowby and A. Siegel; via Eos)

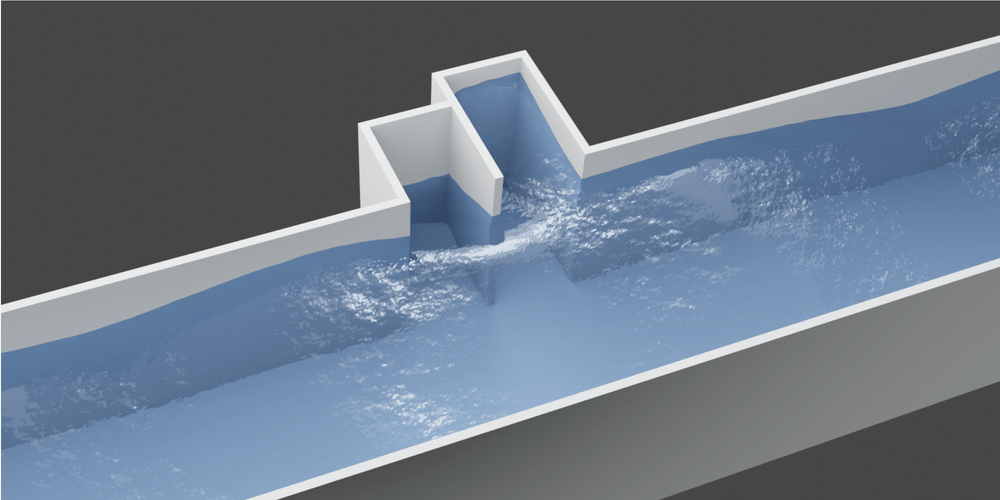

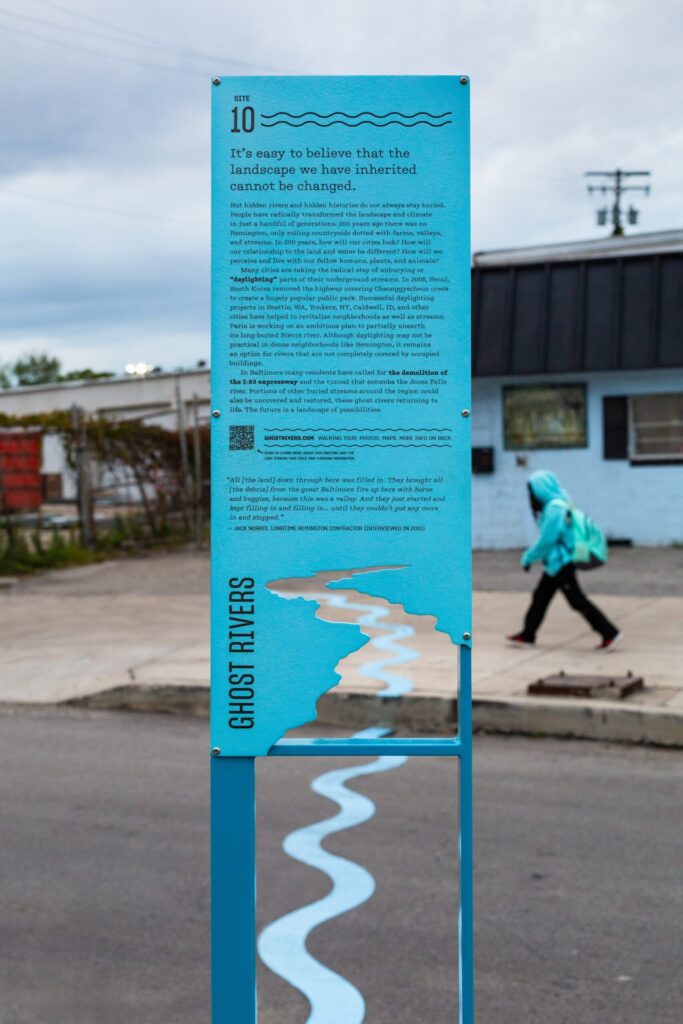

Behind the San Antonio River Walk

How do you manage necessary updates to an iconic landmark like the San Antonio River Walk without disrupting its function? That’s the concept behind this Practical Engineering video, which shows how the city removed and replaced two control gates for the River Walk without ever changing the water level. It’s a neat view both into the engineering of civil water infrastructure and into the practical considerations of how construction on these systems works. (Video credit: Practical Engineering)

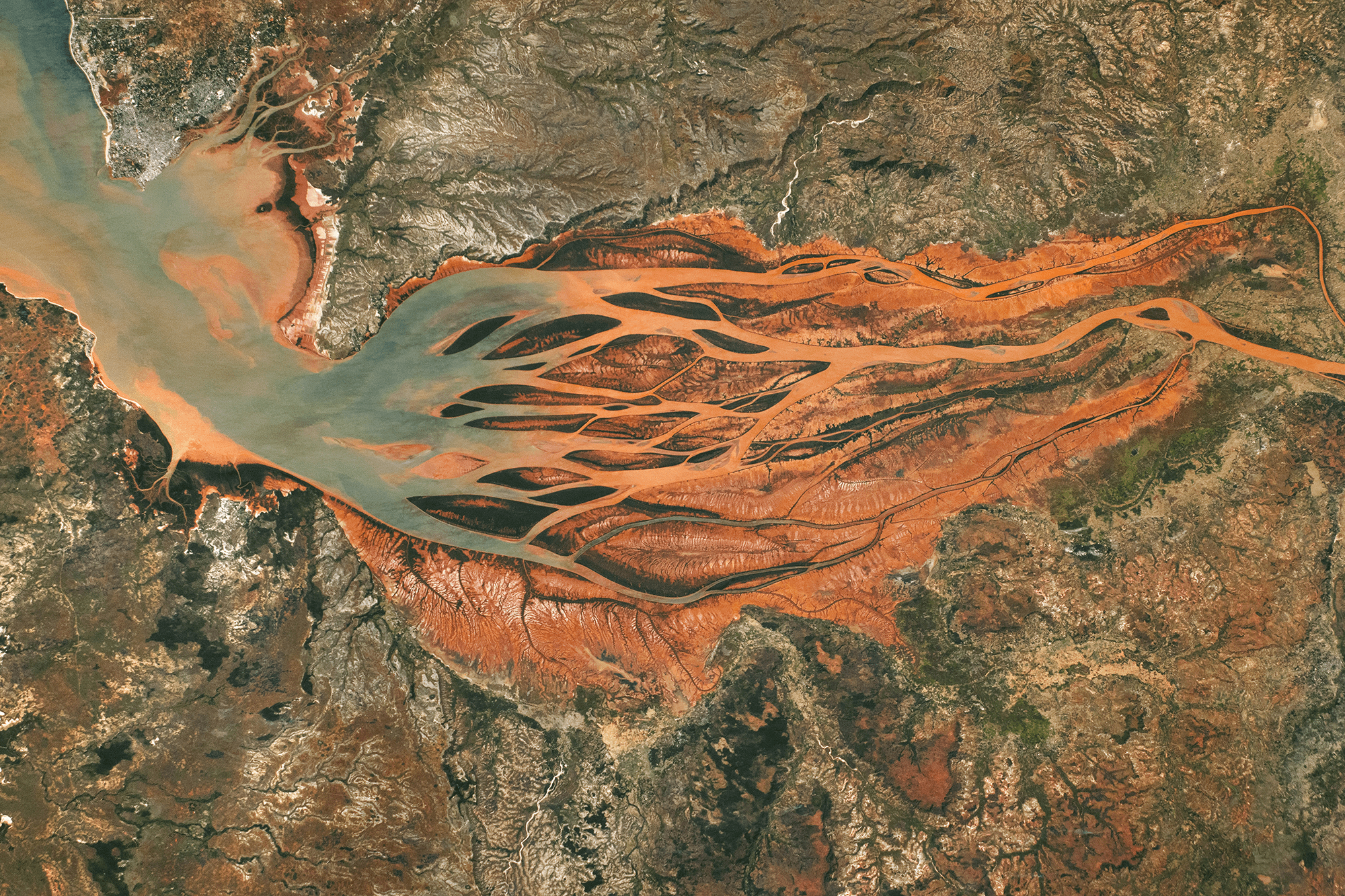

Growing Downstream

This astronaut photo shows Madagascar’s largest estuary, as of 2024. On the right side, the Betsiboka River flows northwest (right to left, in the image). Less than 100 years ago, most of the estuary was navigable by ships, but now more than half of it is taken up by the river delta. Upstream on the river, extensive logging and expansions to farmland have caused severe soil erosion; the river carries that sediment downstream, dyeing the waters reddish-orange. As the river branches and the flow slows, that sediment falls out of suspension, building up islands and seeding new sand bars further downstream.

A difference of 40 years. A 2024 astronaut photo of the Betsiboka River delta compared with one from 1984 (inset). Several islands are labeled in both images. Notice how new islands have formed upstream of the ones seen in 1984. In the image above, you can compare the 2024 delta to the way it looked in 1984. Letters A, B, C, and D mark the downstream-most islands from 1984. Today newer islands and sand bars sit even further downstream. (Image credit: NASA; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Who Killed the Colorado River?

From its source high in the snowy Rocky Mountains, the Colorado River runs through two countries and five states on its way to the Gulf of California. Or at least it used to. The river hasn’t met the sea in decades. All that water disappeared into a complicated web of poor management, short-sighted policies, and human infrastructure, as this video from PBS Terra explores. Unfortunately, while the details vary, this story is not unique, and many rivers around the world are no longer completing their journey. The good news is that we can still change that and rehabilitate the landscapes we’ve lost. (Video and image credit: PBS Terra)

Junggar Basin Aglow

The low sun angle in this astronaut photo of Junggar Basin shows off the wind- and water-carved landscape. Located in northwestern China, this region is covered in dune fields, appearing along the top and bottom of the image. The uplifted area in the top half of the image is separated by sedimentary layers that lie above the reddish stripe in the center of the photo. Look closely in this middle area, and you’ll find the meandering banks of an ephemeral stream. Then the landscape transitions back into sandy wind-shaped dunes. (Image credit: NASA; via NASA Earth Observatory)