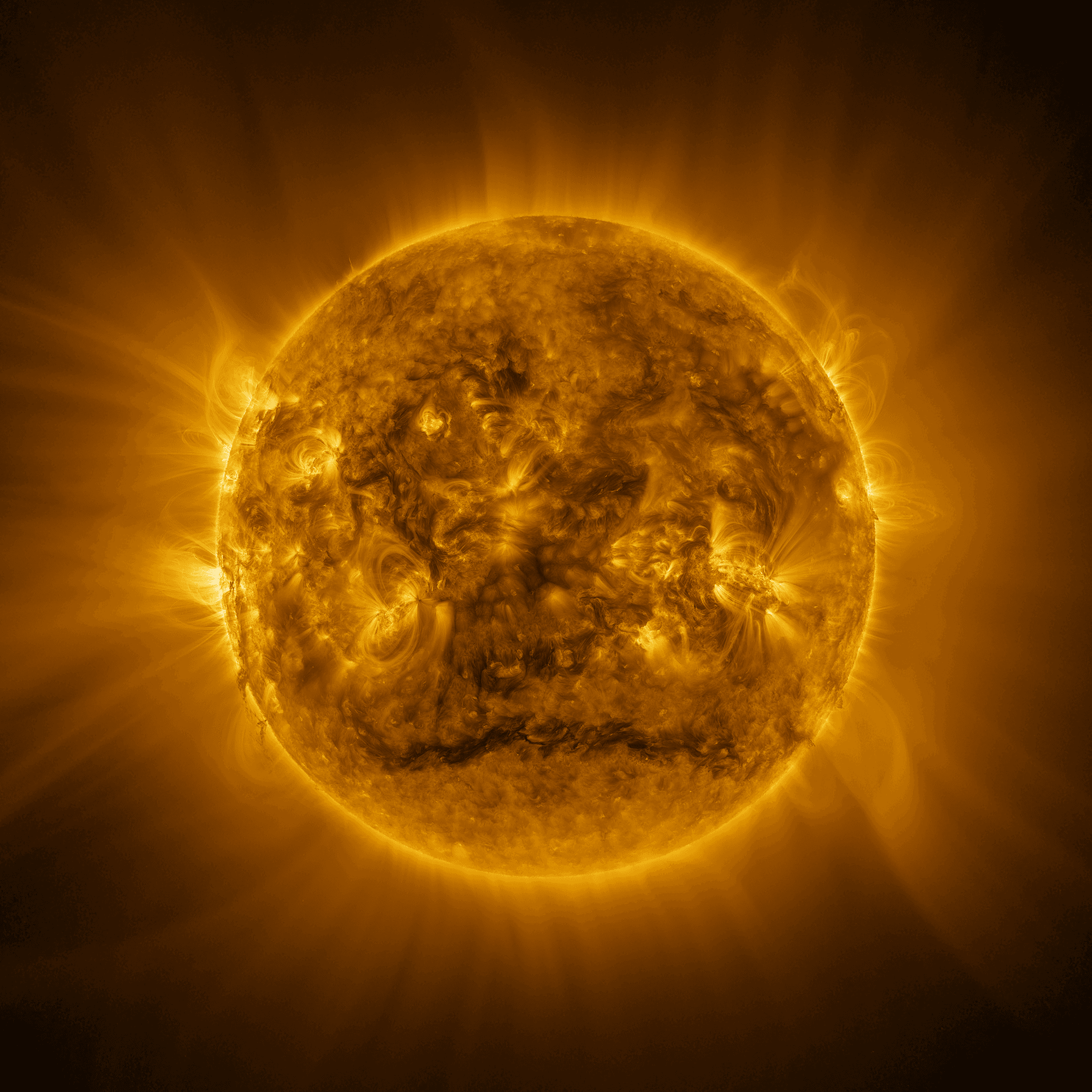

Fall into our nearest star in this gorgeous high-resolution view of the Sun. Taken by Solar Orbiter, a joint NASA-ESA mission, the image stretches from the fiery photosphere — full of filaments and prominences — to the wispy yet unbelievably hot corona. It’s well worth clicking through to zoom in and around the full size image. (Image credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/EUI Team, E. Kraaikamp; via Gizmodo)

Tag: plasma

A Glimpse of the Solar Wind

In December 2024, Parker Solar Probe made its closest pass yet to our Sun. In doing so, it captured the detailed images seen here, where three coronal mass ejections — giant releases of plasma, twisted by magnetic fields — collide in the Sun’s corona. Events like these shape the solar wind and the space weather that reaches us here on Earth. The biggest events can cause beautiful auroras, but they also run the risk of breaking satellites, power grids, and other infrastructure. (Image credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Naval Research Lab; video credit: NASA Goddard; via Gizmodo)

A New Plasma Wave for Jupiter

Jupiter‘s North Pole has a powerful magnetic field combined with plasma that has unusually low electron densities. This combination, researchers found, gives rise to a new type of plasma wave.

Ions in a magnetic field typically move parallel to magnetic field lines in Langmuir waves and perpendicularly to the field lines in Alfvén waves — with each wave carrying a distinctive frequency signature. But in Jupiter’s strong magnetosphere, low-density plasma does something quite different: it creates what the team is calling an Alfvén-Langmuir wave — a wave that transitions from Alfvén-like to Langmuir-like, depending on wave number and excitation from local beams of electrons.

Although this is the first time such plasma behavior has been observed, the team suggests that other strongly-magnetized giant planets — or even stars — could also form these waves near their poles. (Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / SwR I/ MSSS/G. Eason; research credit: R. Lysak et al.; via APS)

A Sprite From Orbit

A sprite, also known as a red sprite, is an upper-atmospheric electrical discharge sometimes seen from thunderstorms. Unlike lightning, sprites discharge upward from the storm toward the ionosphere. This particular one was captured by an astronaut aboard the International Space Station. That’s a pretty incredible feat because sprites typically only last a millisecond or so. The first one wasn’t photographed until 1989. (Image credit: NASA; via P. Byrne)

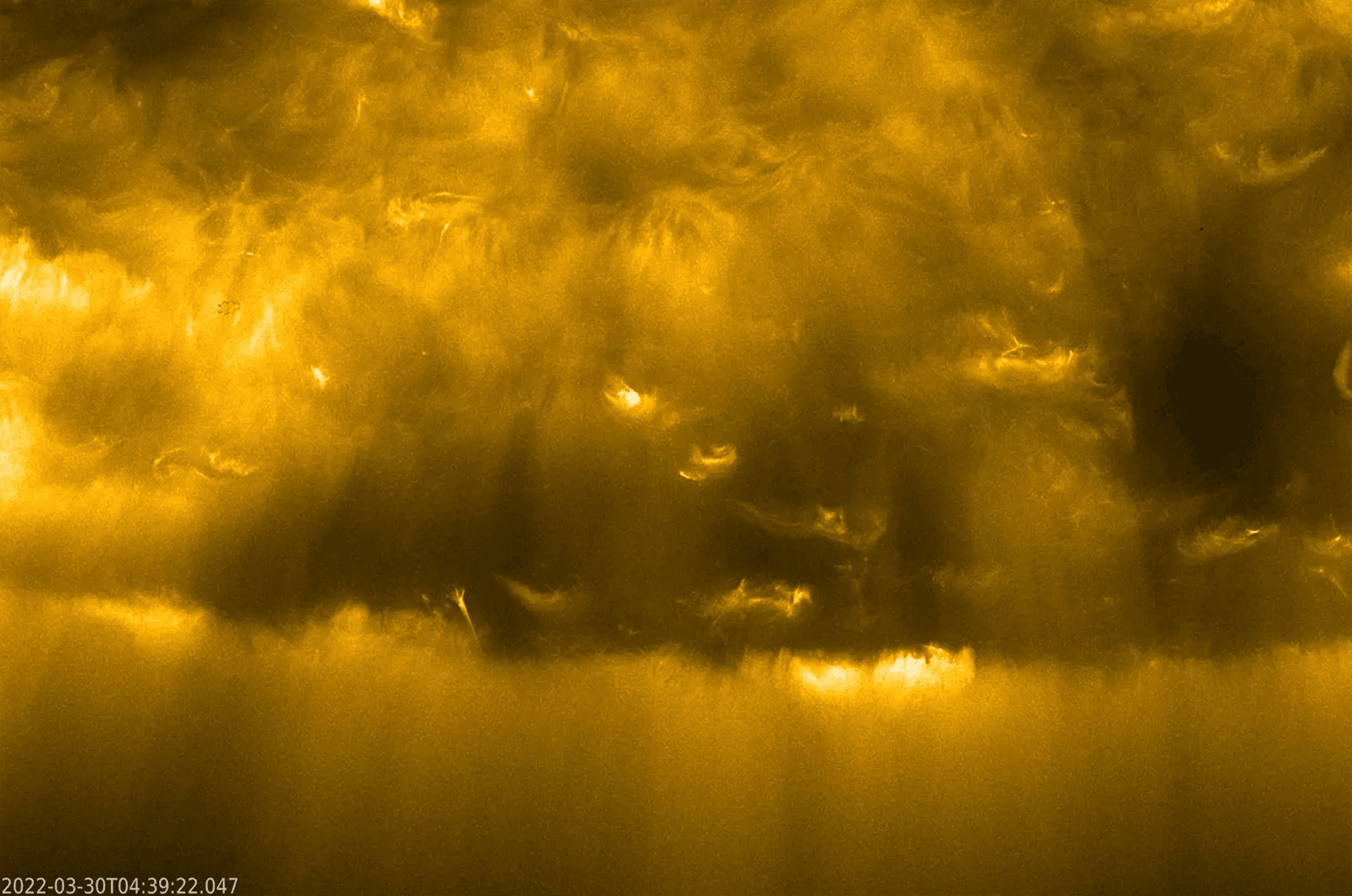

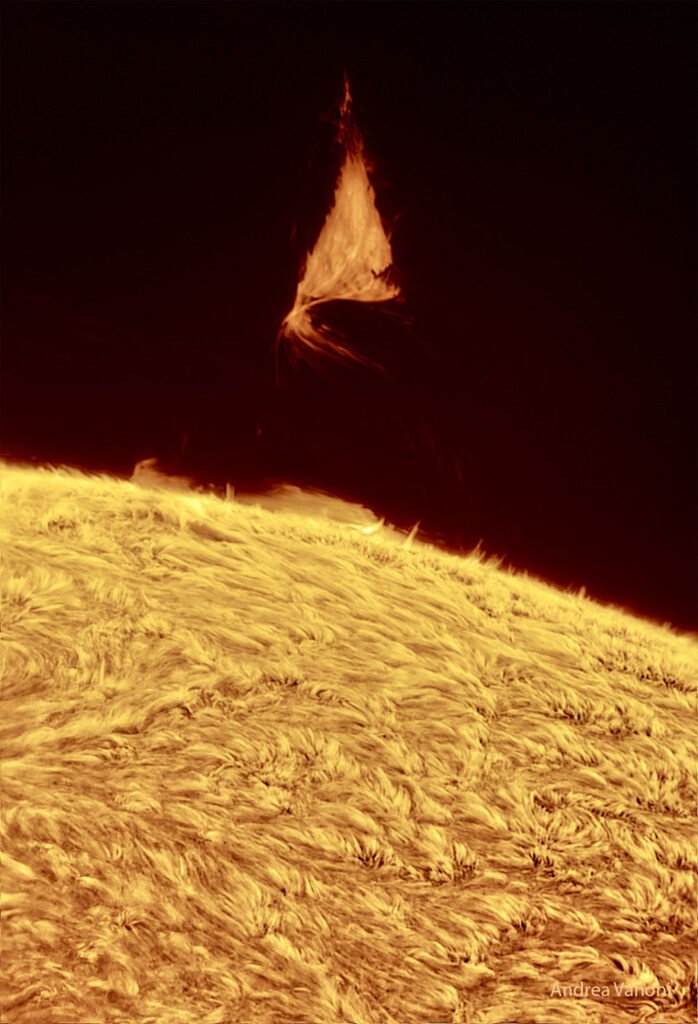

Glimpses of Coronal Rain

Despite its incredible heat, our sun‘s corona is so faint compared to the rest of the star that we can rarely make it out except during a total solar eclipse. But a new adaptive optic technique has given us coronal images with unprecedented detail.

These images come from the 1.6-meter Goode Solar Telescope at Big Bear Solar Observatory, and they required some 2,200 adjustments to the instrument’s mirror every second to counter atmospheric distortions that would otherwise blur the images. With the new technique, the team was able to sharpen their resolution from 1,000 kilometers all the way down to 63 kilometers, revealing heretofore unseen details of plasma from solar prominences dancing in the sun’s magnetic field and cooling plasma falling as coronal rain.

The team hope to upgrade the 4-meter Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope with the technology next, which will enable even finer imagery. (Image credit: Schmidt et al./NJIT/NSO/AURA/NSF; research credit: D. Schmidt et al.; via Gizmodo)

Seeing the Sun’s South Pole For the First Time

The ESA-led Solar Orbiter recently used a Venus flyby to lift itself out of the ecliptic — the equatorial plane of the Sun where Earth sits. This maneuver offers us the first-ever glimpse of the Sun’s south pole, a region that’s not visible from the ecliptic plane. A close-up view of plasma rising off the pole is shown above, and the video below has even more.

Solar Orbiter will get even better views of the Sun’s poles in the coming months, perfect for watching what goes on as the Sun’s 11-year-solar-cycle approaches its maximum. During this time, the Sun’s magnetic poles will flip their polarity; already Solar Orbiter’s instruments show that the south pole contains pockets of both positive and negative magnetic polarity — a messy state that’s likely a precursor to the big flip. (Image and video credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/EUI Team, D. Berghmans (ROB) & ESA/Royal Observatory of Belgium; via Gizmodo)

Jets, Shocks, and a Windblown Cavity

As material collapses onto a protostar, these young stars often form stellar jets that point outward along their axis of rotation. Made up of plasma, these jets shoot into the surrounding material, their interactions creating bright parabolic cavities like the one seen here. This is half of LDN 1471; the protostar’s other jet and cavity are hidden by dust but presumably mirror the bright shape seen here. (The protostar itself is the bright spot at the parabola’s peak.) Although the cavity is visibly striated, it’s not currently known what causes this feature. Perhaps some form of magnetohydrodynamic instability? (Image credit: NASA/Hubble/ESA/J. Schmidt; via APOD)

Eerie Aurora

This surreal image comes from an aurora on Halloween 2013. Photographer Ole C. Salomonsen captured it in Norway during one of the best auroral displays that year. The shimmering green and purple hues are the glow of oxygen and nitrogen in the upper atmosphere reacting to high-energy particles streaming in from the solar wind. These geomagnetic storms can disrupt GPS satellites, compromise radio communication, and even corrode pipelines, but they also create these stunning nighttime displays. (Image credit: O. Salomonsen; via APOD)

A Plasma Arc Lights

Plasma lighters — as their name indicates — use plasma in place of burning butane. Plasma — our universe’s most common state of matter — is a gas that’s been stripped of its electrons, ionizing it so that it’s electrically and magnetically active. In these lighters (as well as other plasma generators), a high-voltage current jumps between two nodes to ignite the spark. In effect, it’s a tiny lightning bolt you can hold in your hand. (Though I don’t recommend that you try to literally hold it; plasma burns suck.) (Video and image credit: J. Rosenboom; via Nikon Small World in Motion)

An arc of plasma from a plasma lighter dances.