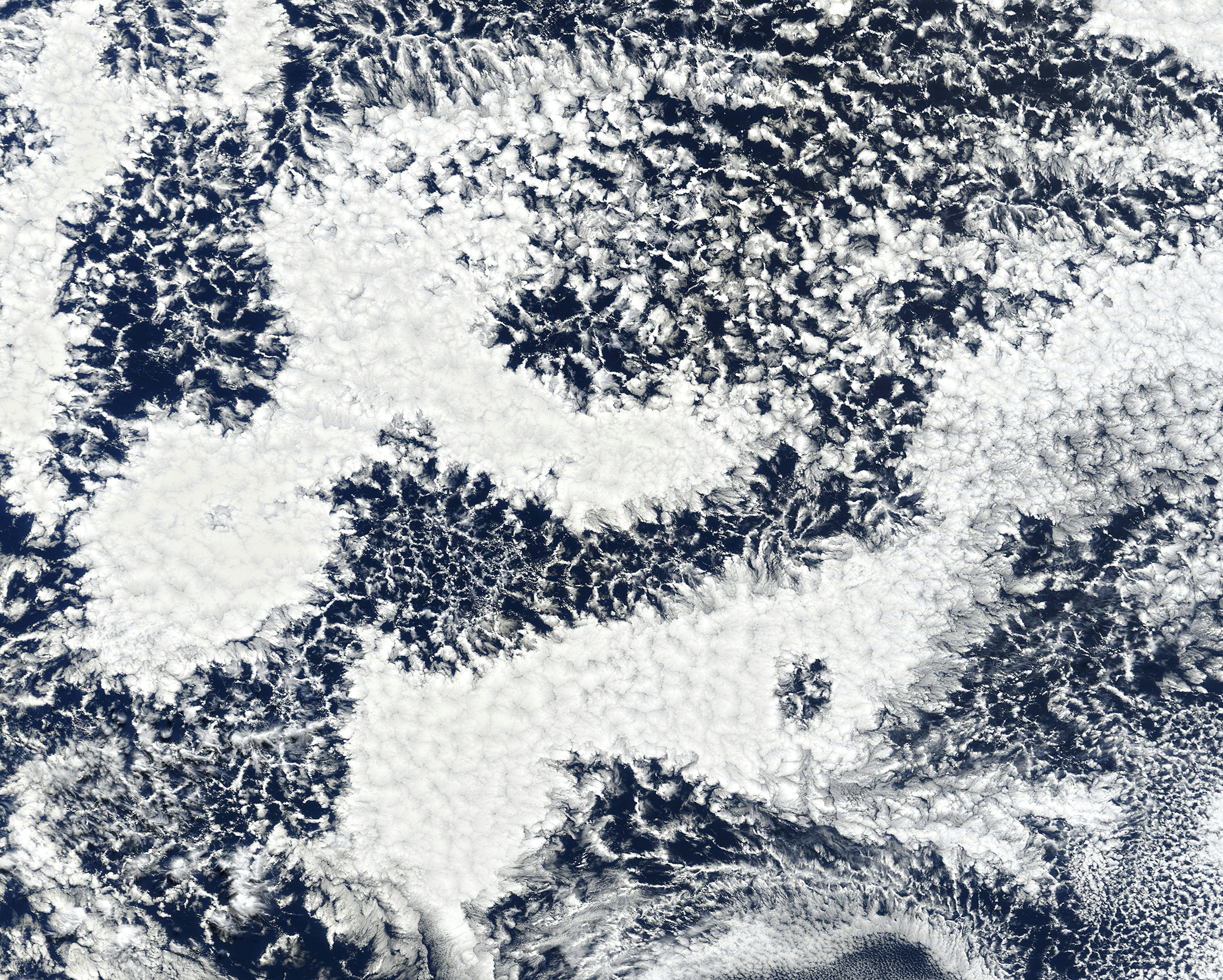

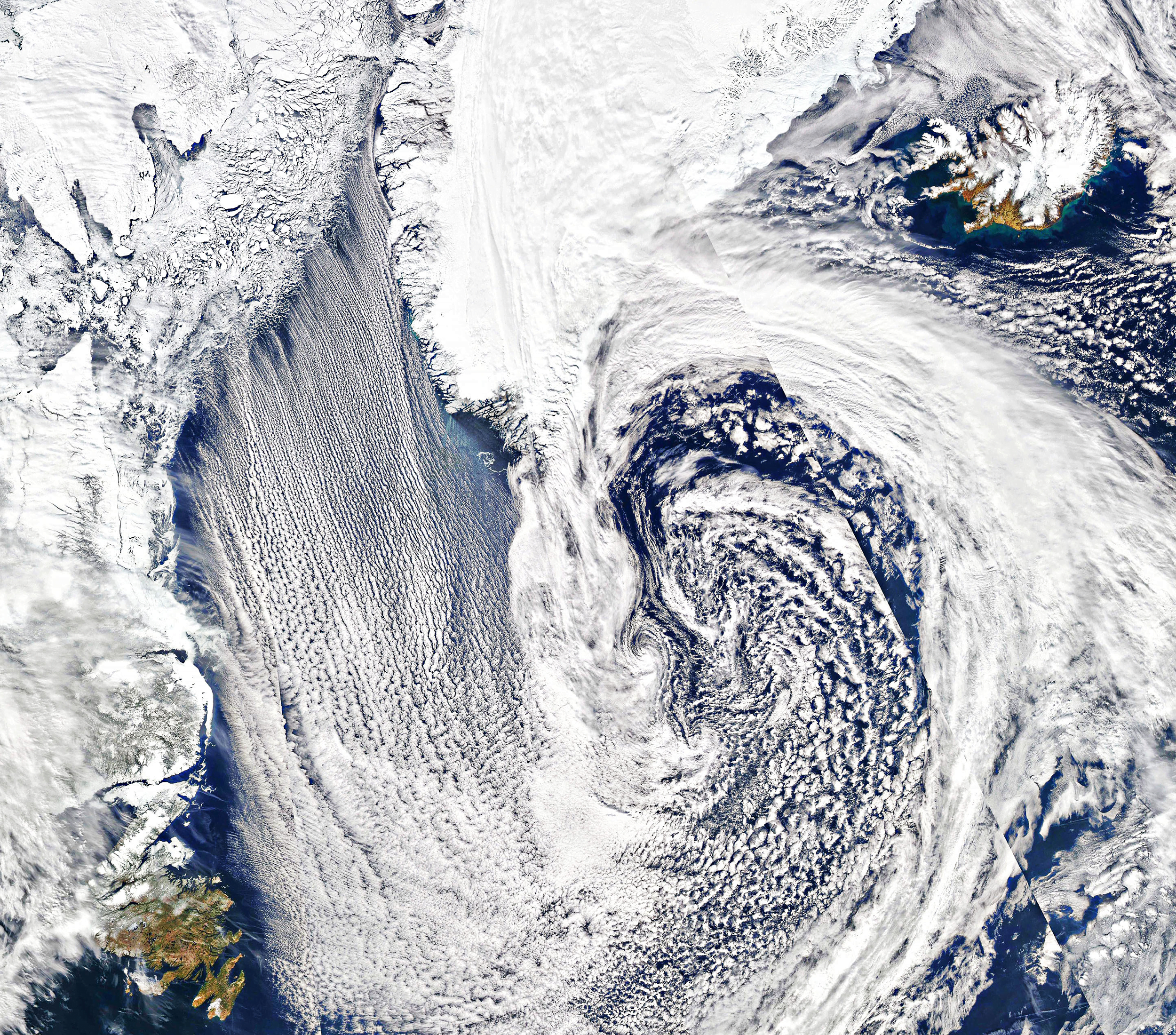

Summertime in the middle U.S. means thunderstorms, many of which can form long lines of storms known as squall lines. Complex convective dynamics feed such storms. Here is an illustration of one part of a squall’s lifecycle:

As it falls, rain evaporates, cooling air near the ground and forming a cold pool. If incoming winds block the cold pool from spreading, the pool will act instead as a ramp that redirects the wind upward, carrying any warmth and moisture up into the storm cloud. Wind shear — a vertical variation in wind strength with altitude — creates positve vorticity that opposes the negative vorticity inherent to the cold pool. Together these two regions of opposing vorticity lift more air and moisture into the squall, generating more clouds and more rainfall. (Image credit: top – J. Witkowski, illustration – C. Muller and S. Abramian; see also C. Muller and S. Abramian)