Normally, freezing is a slow enough process that transient phenomena like ripples get smoothed out. But with the right conditions, even ripples can get frozen in time. This picture shows a backyard bird bath after a frigid winter storm passed overnight. For much of that time, the wind was active enough to keep the bath’s water from freezing. But when freezing did start, it happened so rapidly that the wavelets generated by the wind got frozen in place, too. Here’s a similar-looking effect (also in Colorado, ironically) that’s thought to have formed entirely differently. (Image credit: K. Farrell; via EPOD; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Tag: instability

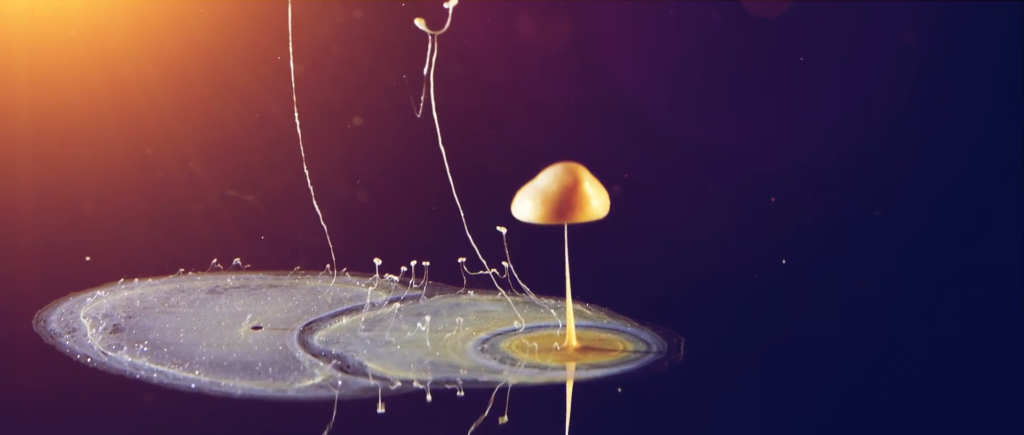

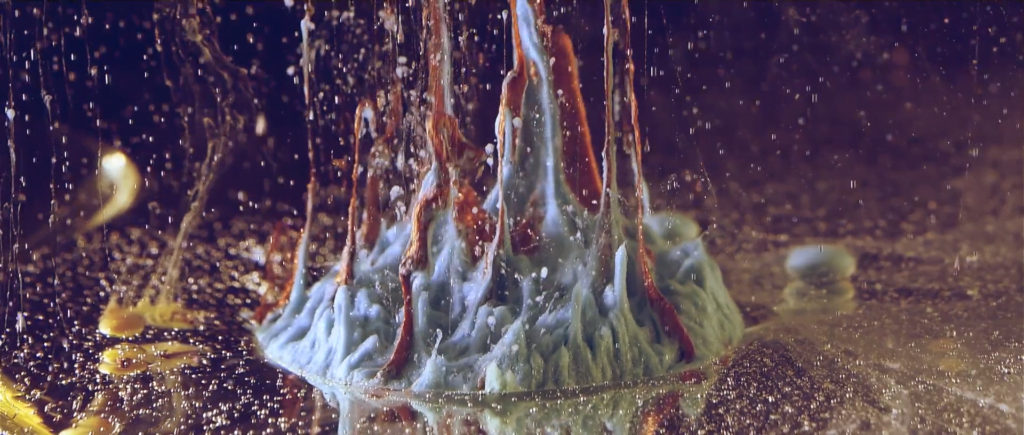

“Aquakosmos”

Colorful chandeliers, passing spirits, sprouting mushrooms, and fountains of falling ink appear in Christopher Dormoy’s “Aquakosmos.” Driven by the slight density difference between ink and water, many of these elaborate shapes result from the Rayleigh-Taylor instability. Anytime you see mushroom-like plumes and chandelier-like splitting vortex rings, there’s probably a Rayleigh-Taylor instability behind it. Check out the full video above, and, if you want to give this kind of flow visualization a try yourself, a glass of water and vial of food coloring is a great place to start. (Video and image credit: C. Dormoy)

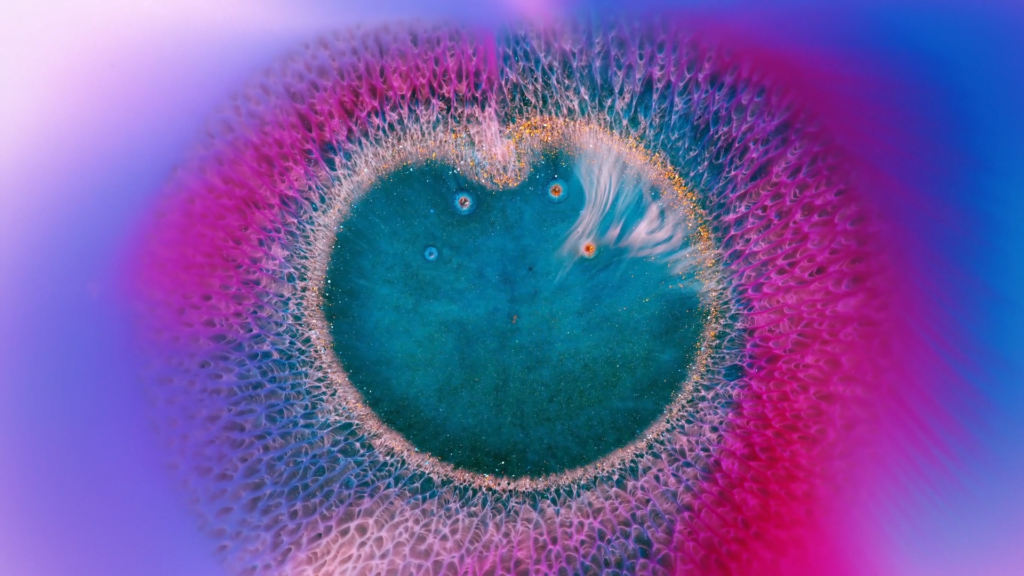

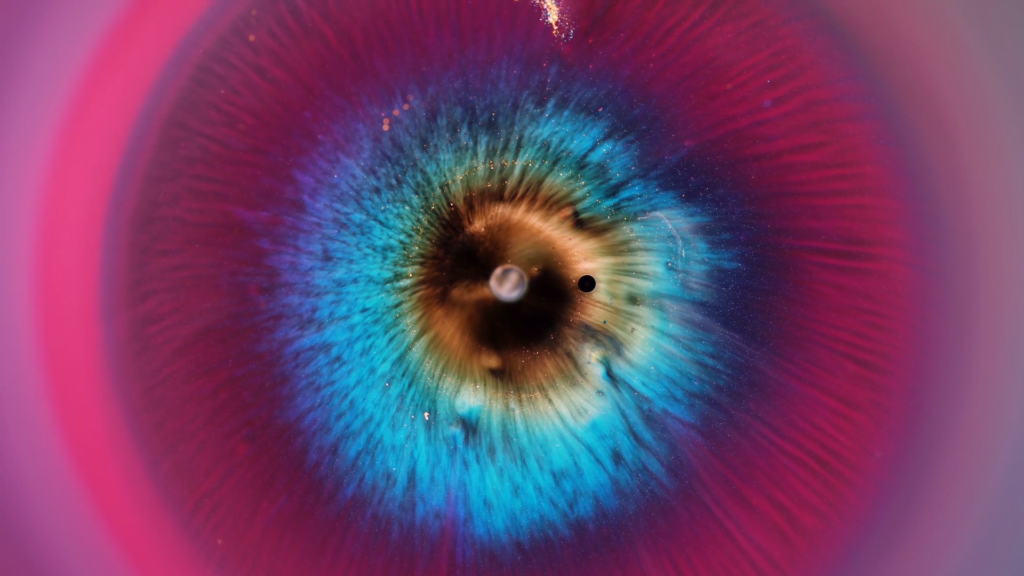

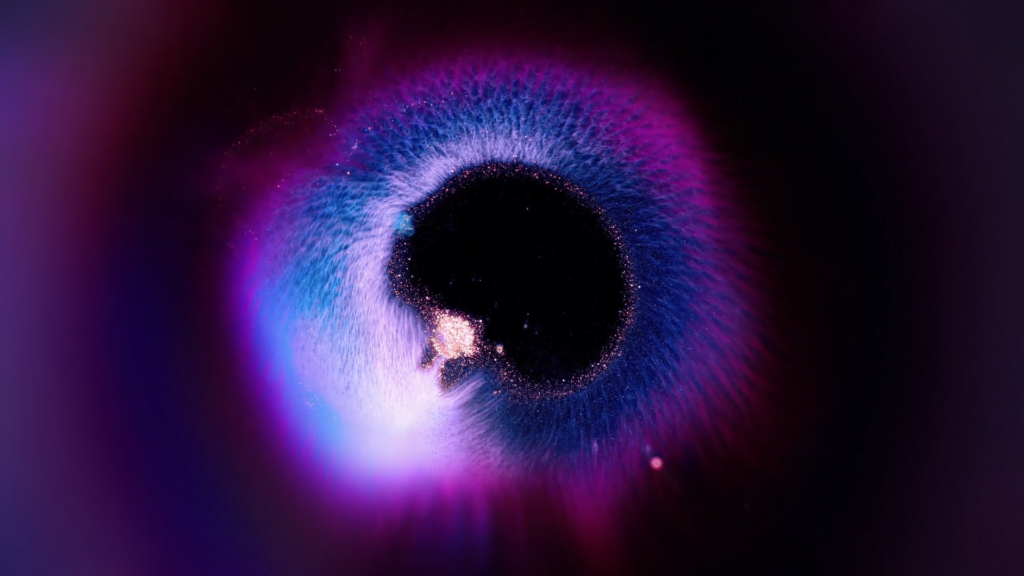

“Space Iris”

Ruslan Khasanov’s “Space Iris” explores the similarities between nebulae and eyes. Made entirely with common fluids like paint, soap, and alcohol, the film shows off the gorgeous possibilities of surface-tension- and density-driven instabilities. Marangoni flows abound! I even see some hints of solutal convection, perhaps? (Video and image credit: R. Khasanov; via Colossal)

Liquid Lens Rupture

A blob of sunflower oil floating on soapy water forms a disk known as a liquid lens. But add some dyed ethanol and things take a turn. The lens rapidly expands and distorts as the ethanol and soapy water meet. These surface flows are driven by the imbalance of surface tension between the different liquids. The liquid lens deforms and abruptly ruptures, releasing dye and ethanol before rebounding into a stable lens again. Adding more ethanol to the lens will repeat the cycle. (Image credit: C. Kalelkar and P. Dey; research credit: D. Maity et al.)

Bubble Trails – Straight or Wonky?

Watch the bubbles rising in a glass of champagne and you’ll see them form tiny straight lines, with each bubble following its predecessor. But in a carbonated soda, the bubbles rise all over the place, each following its own zig-zaggy line. Why the difference? A recent study points out the culprits: bubble size and surfactants.

As bubble size increases from left to right, the bubble trail straightens. Looking at a variety of beverage scenarios, researchers found that both a bubble’s size and its surfactant concentration affected what sort of path it followed. For clean (surfactant-free) bubbles, small bubbles take a winding path, but bigger ones move in a straight line. Simulations show that bubbles can only form a straight path if they produce enough vorticity on their surface. Small bubbles just can’t deform enough to do that.

For bubbles of the same size, increasing the surfactants on the bubbles straightens their path. When surfactants get added, though, the story changes. For bubbles of a set size, adding surfactants made their paths straighter. This was due, the team found, to a bump in vorticity provided by the stabilizing effect of the surfactants. Champagne, they concluded, has straight bubble paths despite its tiny bubbles because of the drink’s high number of flavorful surfactants. (Image credit: top – D. Cook, experiments – O. Atasi et al.; research credit: O. Atasi et al.; via APS Physics)

Polymers and Fluid Sheets

Even adding a small amount of polymers to a fluid can drastically change its behavior. Often polymer-doped fluids act more like soft solids, able to hold their shape like your toothpaste does when squeezed onto your toothpaste. Under a little stress, though, the fluids still flow; that’s why your toothpaste gets less viscous as you scrub.

To study the changes polymers make, this research team collides two jets of fluid to create a liquid sheet. Depending on the flow rate and the added polymers, the break-up pattern of the sheet changes. By observing changes in the sheet thickness and the holes that form, they can draw conclusions about what the polymers are doing. (Video credit: C. Galvin et al.)

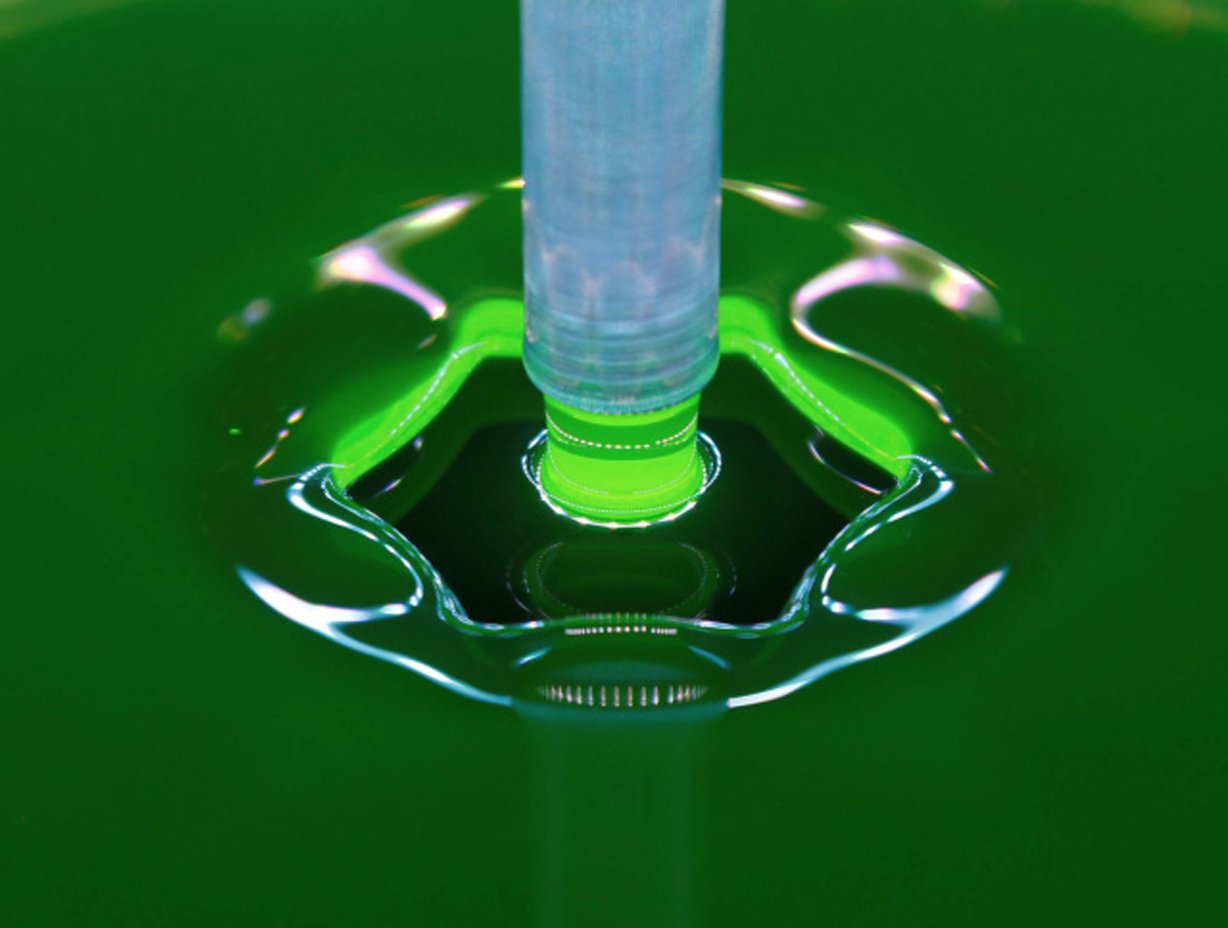

Polygonal Jumps

When you turn on your kitchen faucet, you may have noticed a big circle that forms on the bottom of the sink. This is a hydraulic jump, a region where fast-moving, shallow flow shifts to a slower-moving, deeper flow. Although these jumps start out circular, if the fluid is deeper than a critical value, the jump will break down and form polygons, like the one above. Exactly what shape the jump forms depends on many factors: flow speed, fluid depth, and flow history. The same flow conditions can even form more than one shape. But all of these shapes have one thing in common: their corners are universally around 114 degrees with a radius of 3.5 millimeters. (Image and research credit: S. Tamim et al.; via PRF)

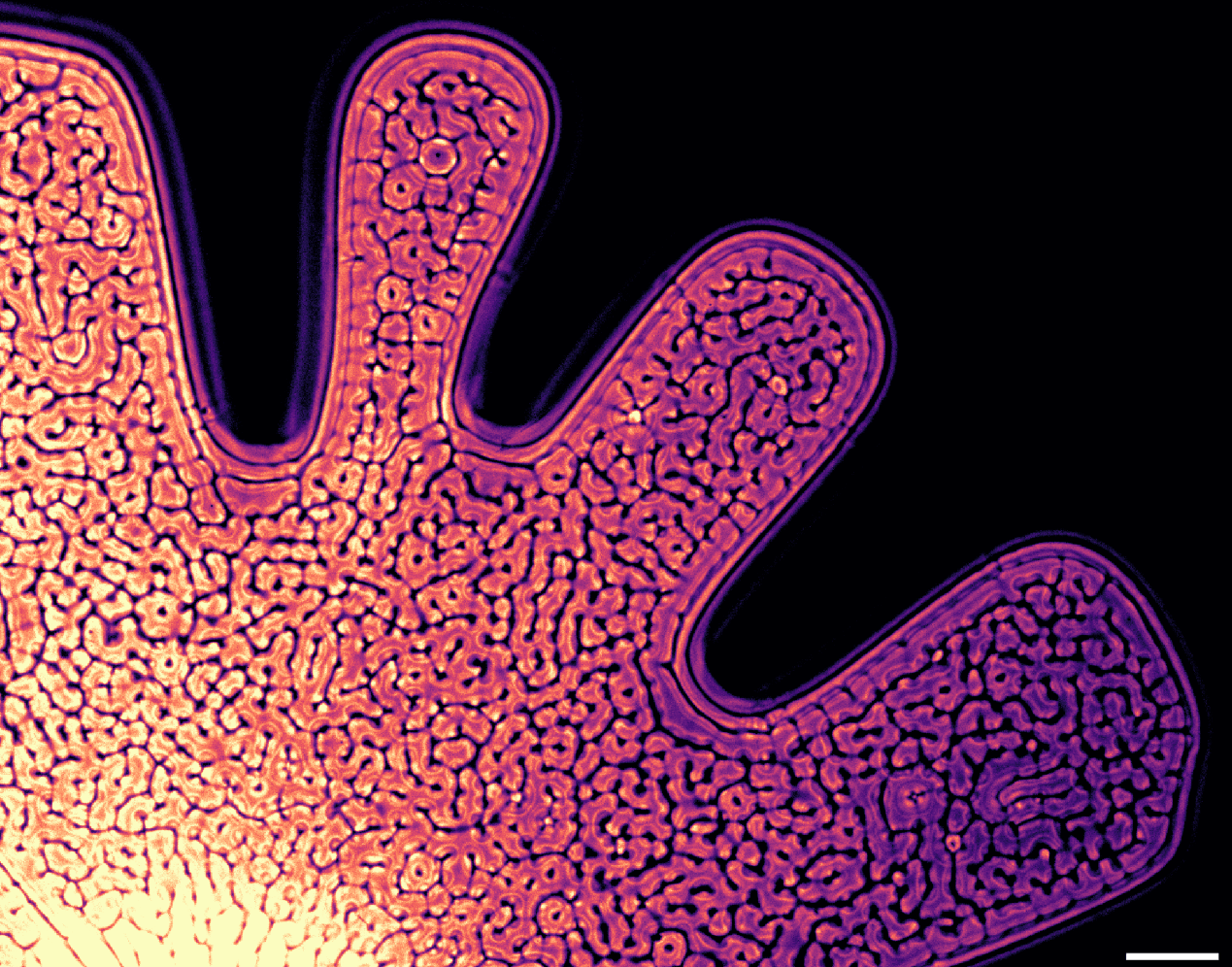

Instabilities on Instabilities

The world of fluid instabilities is a rich one. Combine fluids with differing viscosities, densities, or flow speeds and they’ll often break down in picturesque and predictable manners. Here, researchers explore the Rayleigh-Taylor instability (RTI), which occurs when a denser fluid sits above a less dense one (in a gravitational field). It’s an extremely common instability, showing up in both the cream in your ice coffee and the shape of a supernova’s explosion. It’s very difficult to set up and observe, though, which is where the real cleverness of this experiment stands out.

To study the RTI, these researchers first created another instability, the Saffman-Taylor instability. They filled the space between two glass plates with a viscous fluid, then injected a less viscous one. That created the distinctive viscous fingering pattern seen in the top image. In addition to being less viscous, the injected fluid was also less dense. As it pushed into the original fluid, it displaced some of it, creating a three-layer structure with dense fluid over less-dense fluid over dense fluid. That laid the groundwork for the Rayleigh-Taylor instability form.

A side-view through the fluid mixture shows the characteristic mushroom-like plume of the Rayleigh-Taylor instability. Check out the cell-like pattern distributed across the fluid in the top image. These are plumes formed in the RTI as dense fluid sinks into the less-dense fluid below it. From the side (see second image), each plume takes on the distinctive mushroom-like shape of a Rayleigh-Taylor instability. Given time, the two fluids mix and the cellular pattern disappears. But until then, this set-up uses one instability to study a second one. How cool is that?! (Image and research credit: S. Alqatari et al., see also)

“Dark Matter”

In “Dark Matter” photographer Alberto Seveso captures billowing black pigment against a bright red backdrop. Seveso excels at capturing the developing turbulence in sinking fluids. I’m always blown away by the texture in his images; it almost makes the fluid look fabric-like and solid. Look closely in some of these images and you can catch a few tiny Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities, too, as the denser pigment sinks through water. (Image credit: A. Seveso)

Paint Ejection

Shaking paint on a speaker cone and filming it in high speed is an oldie but a goodie. Here, artist Linden Gledhill films paint ejection at 10,000 frames per second, giving us a glorious view of the process. As the paint flies upward, accelerated by the speaker, it stretches into long ligaments. As the ligaments thin, surface tension concentrates the paint into droplets, connected together by thinning strands. When those strands break, they snap back toward the remaining paint, imprinting swirling threads of different colors, thanks to their momentum. Eventually, surface tension wins the tug-of-war and transforms all the paint into droplets. (Video and image credit: L. Gledhill)