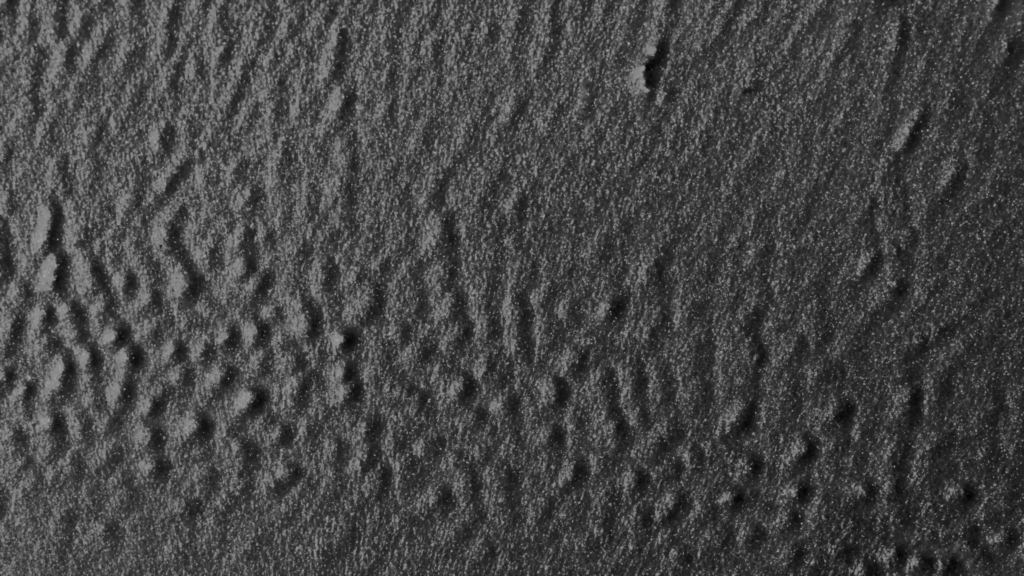

Branching cracks wend through the slopes of Utah in this photograph by Matt Payne. It may seem strange to feature something so dry on a blog about fluid dynamics, but everything seen here depends as much on air and water as on soil, rock, and sand. How water intrudes into the porous landscape and the way it evaporates back out is critical to crack formation. (Image credit: M. Payne; via ILPOTY)

Tag: granular material

Instabilities in a Particle Flow

Even though particles are not (strictly speaking) a fluid, they often behave like one. Here, researchers investigate what happens when two layers of particles–with different size and density–slide down an incline together. The video is tilted so that the flow instead appears from left to right.

When the larger, denser particles sit atop a layer of smaller, lighter particles, shear between the two layers causes a Kelvin-Helmholtz instability that runs in the direction of the flow. This creates a wavy interface that lets some small particles work upward while large particles shift downward.

At the same time, a slice across the flow shows that plumes of small particles are pushing up toward the surface, driven by a Rayleigh-Taylor instability. The researchers also look at what happens when the particles are fluidized by injecting a gas able to lift the particles. (Video and image credit: M. Ibrahim et al.; via GFM)

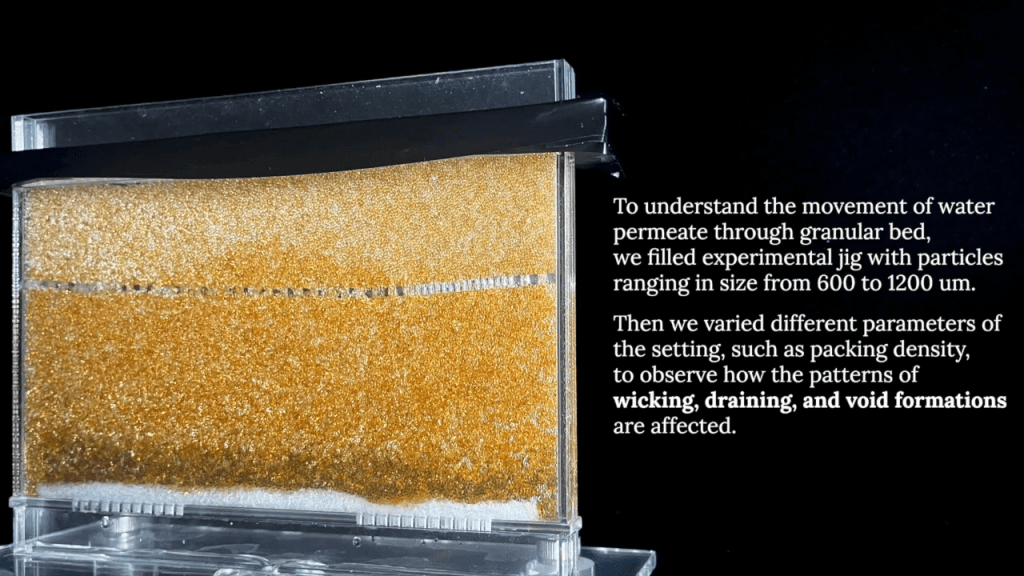

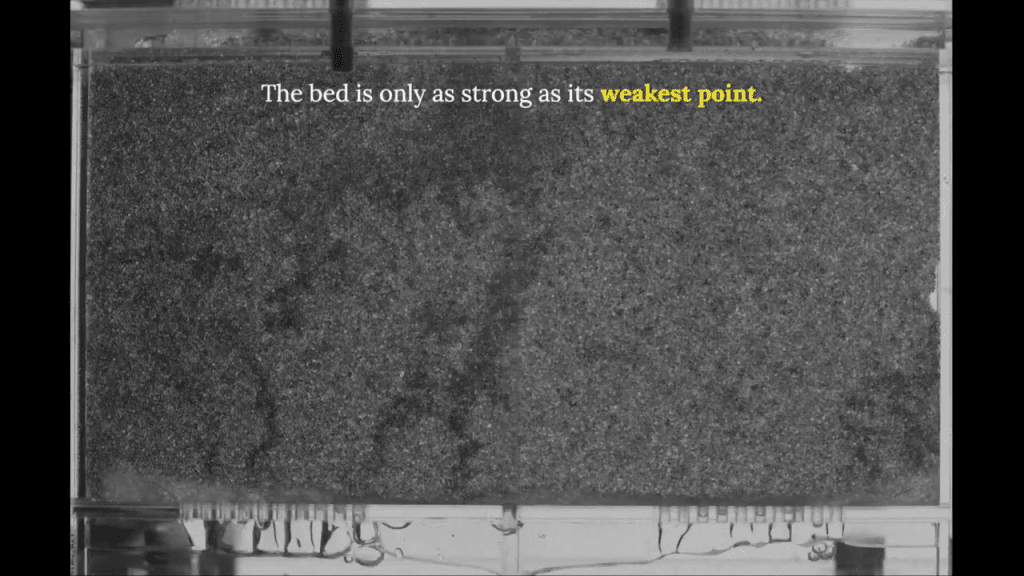

Flow Through Granular Beds

We often rely on water draining through beds of grains, whether it’s the soil foundation beneath a building or the sand-and-gravel-filter used in water treatment. But how does water move through these tortuous porous passages? That’s what we see in this video, which places grains in a jig resembling an ant farm and lets us watch as water–and air–drain through the grains. The result is more complicated than you might imagine, with dry pockets, weak spots, and developing sinkholes. (Video and image credit: J. Choi et al.)

How the Edenville Dam Failed

Back in May 2020, the Edenville Dam in Michigan failed dramatically, releasing flood waters that destroyed a downstream dam and caused millions of dollars of damage. In this Practical Engineering video, Grady deconstructs the accident, based on an interim report from the forensic team charged with investigating the failure. Along the way, he explains common causes of dam failures, what made the Edenville failure unusual, and how engineers build modern earthen dams to avoid this older design’s flaws. (Image and video credit: Practical Engineering)

Waves Over Sand Ripples

Look beneath the waves on a beach or in a bay, and you’ll find ripples in the sand. Passing waves shape these sandforms and can even build them to heights that require dredging to keep waterways passable to large ships. To better understand how the sand interacts with the flow, researchers build computer models that couple the flow of the water with the behavior of individual sand grains. One recent study found that sand grains experienced the most shear stress as the flow first accelerates and then again when a vortex forms near the crest of the ripple. (Image credit: D. Hall; research credit: S. DeVoe et al.; via Eos)

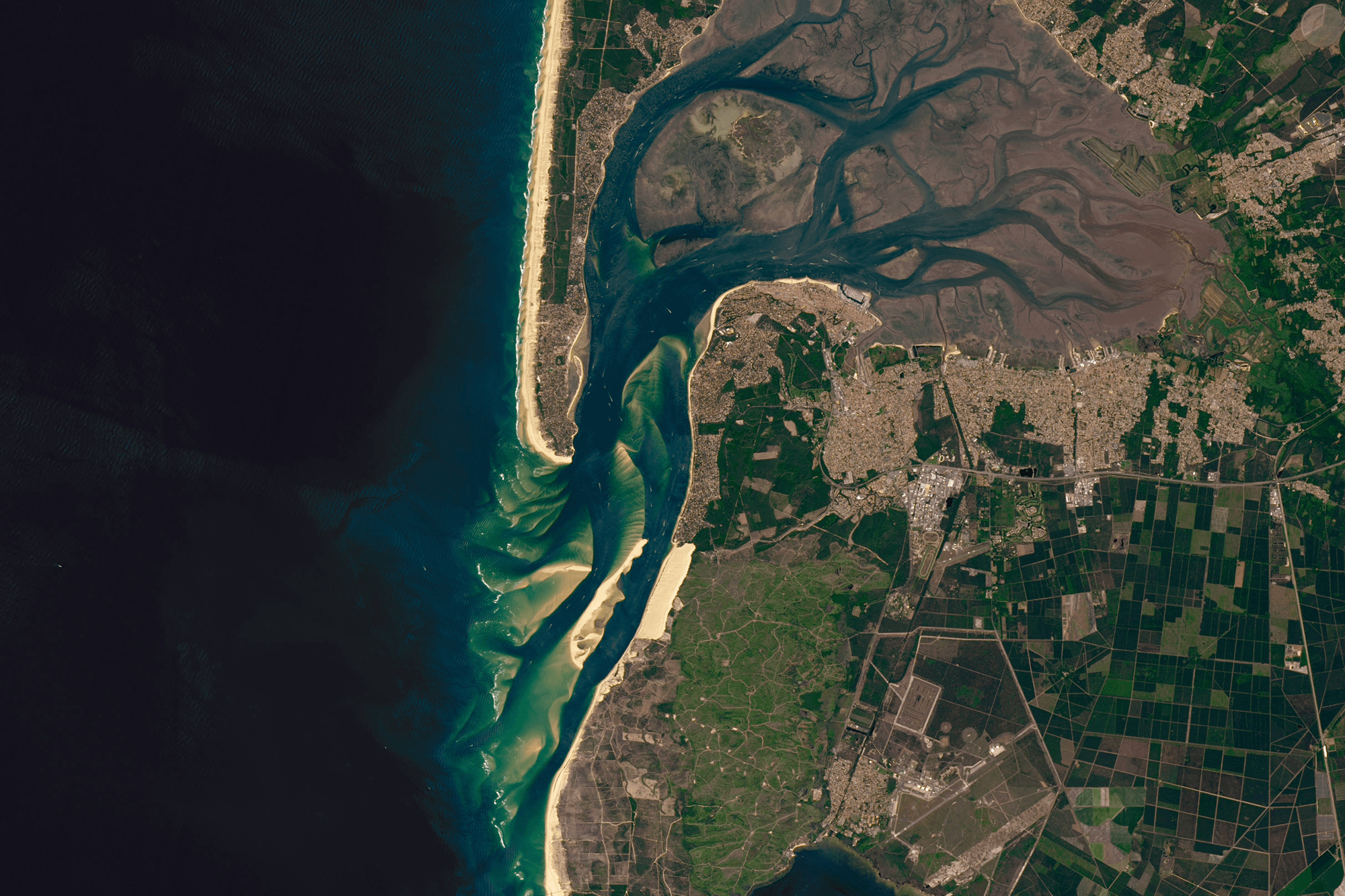

La Grande Dune du Pilat

Southwest of Bordeaux in France stands Europe’s tallest sand dune, La Grande Dune du Pilat. Some 2.7 kilometers long and over 100 meters high, this dune took shape here over thousands of years. It moves inland a few meters every year as winds blowing from the Atlantic push sand up its shallow seaward side to the dune’s crest. There, sand will avalanche down the steeper leeward side, advancing the dune little by little. The dune’s accumulation has not been steady; during cooler and drier times, sand has collected there, but it took warmer and wetter climes to grow the forests that have helped stabilize the soil and build the dune higher. Humanity has played a role as well, at times introducing new tree species to stabilize the dune. (Image credit: W. Liang; via NASA Earth Observatory)

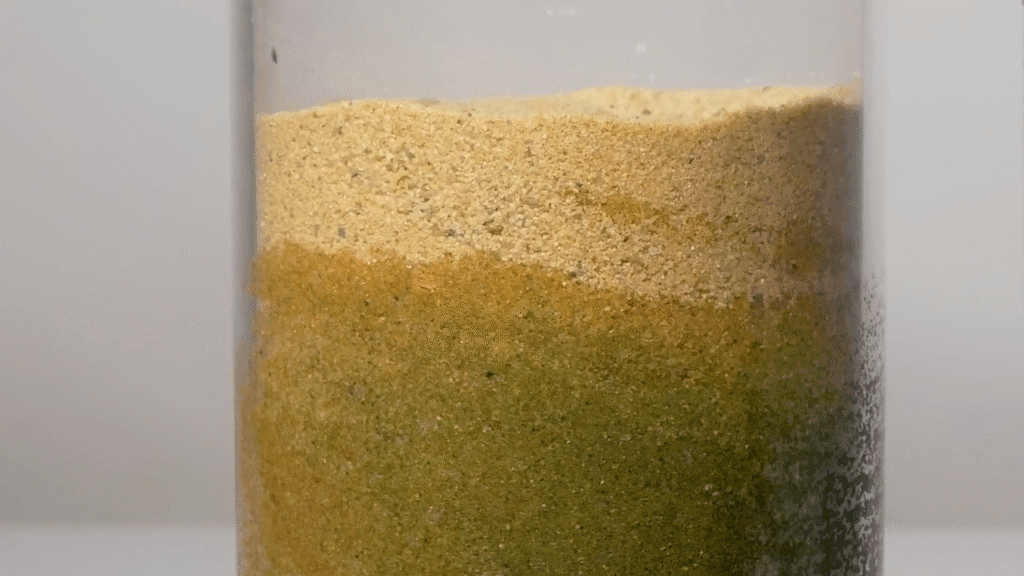

Pour-Over Physics

Fluids labs are filled with many a coffee drinker, and even those (like me) who don’t enjoy coffee, can find plenty of fascinating physics in their labmates’ mugs. Espresso has received the lion’s share of the research in recent years, but a new study looks at the unique characteristics of a pour-over coffee. In this technique, coffee grounds sit in a conical filter and a stream of hot water pours over the top of the grounds. Researchers found that the ideal pour creates a powerful mixing environment in a coffee-studded water layer that sits above a V-shaped bed of grains created by the falling water jet.

The best mixing, they find, requires a pour height no greater than 50 centimeters (to prevent the jet from breaking into drops) but with enough height that the falling jet stirs up the grounds. You also want to pour slowly enough to give plenty of time for mixing, without letting the jet stick to the kettle’s spout, which (again) causes the jet to break up.

That ideal pour extracts more coffee flavor from the grounds, allowing you to get the same strength of brew from fewer beans. As climate change makes coffee harder to grow, coffee drinkers will want every trick to stretch their supply. (Image credit: S. Satora; research credit: E. Park et al.; via Ars Technica)

On the Mechanics of Wet Sand

Sand is a critical component of many built environments. As most of us learn (via sand castle), adding just the right amount of water allows sand to be quite strong. But with too little water — or too much — sand is prone to collapse. For those of us outside the construction industry, we’re most likely to run into this problem on the beach while digging holes in the sand. In this Practical Engineering video, Grady explains the forces that stabilize and destabilize piled sand and where the dangers of excavation lie. (Video and image credit: Practical Engineering)

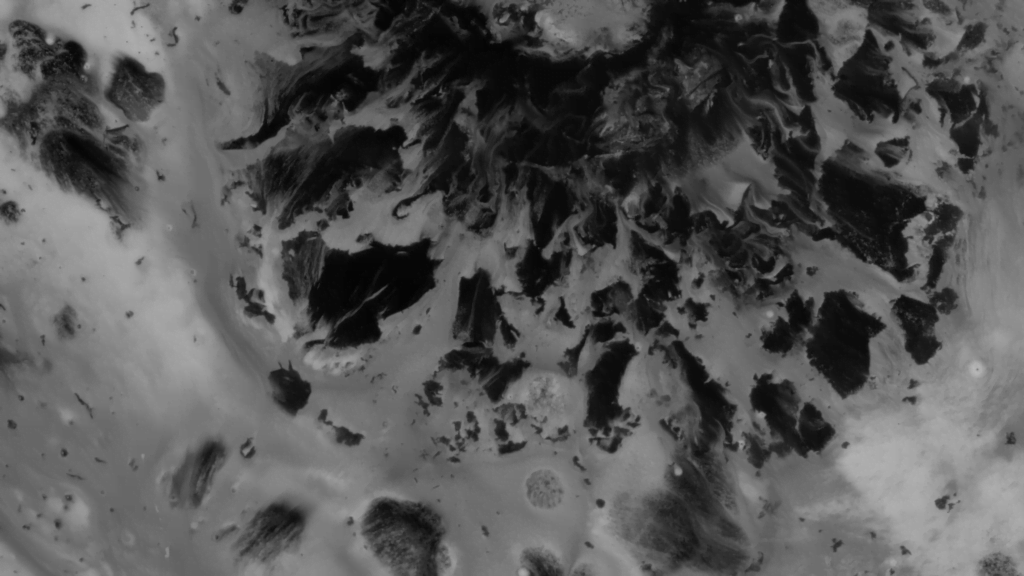

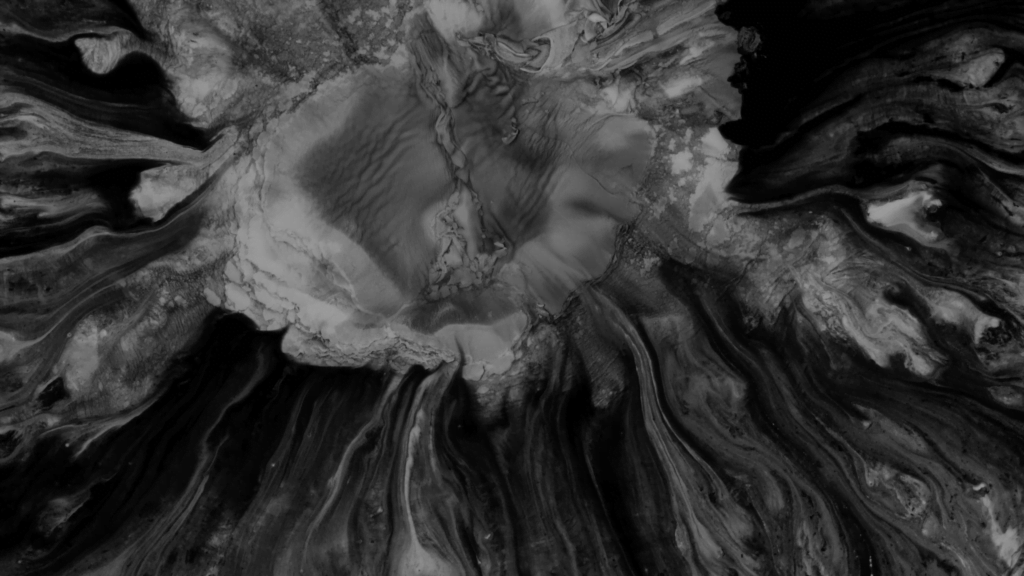

“Dispersion”

In “Dispersion,” particles spread under the influence of an unseen fluid. Like Roman de Giuli’s work, filmmaker Susi Sie creates macro images that look like ice floes, deserts, and river deltas viewed from above. This similarity of patterns at both large and small scales is a specialty of fluid physics. Just as artists use it to mimic larger flows, scientists use it to study planet-scale problems in the lab. (Video and image credit: S. Sie et al.)

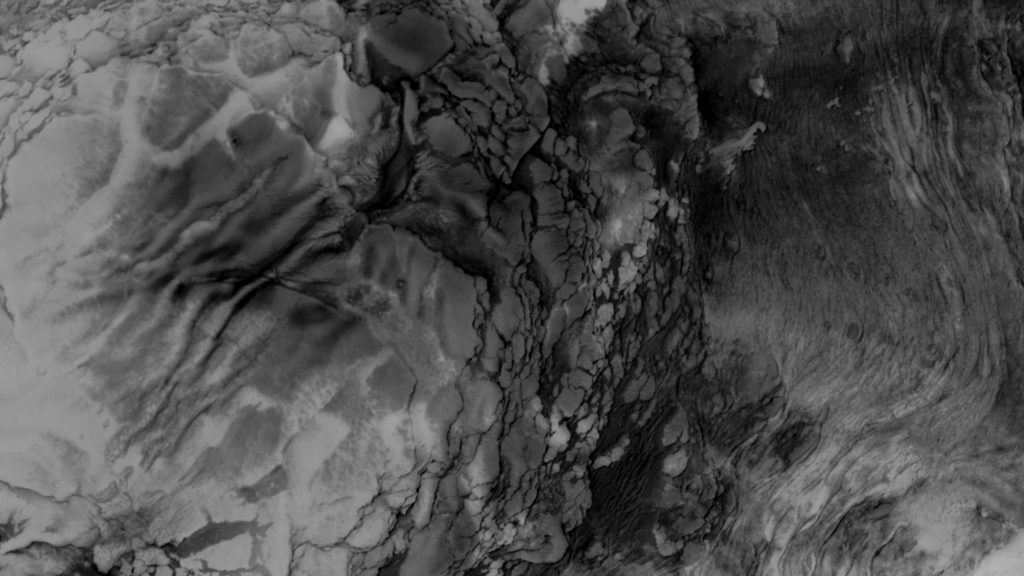

Thawing Permafrost Primes Slumps

As permafrost thaws on Arctic hillsides and shorelines, the land often deforms in a unique fashion, known as a slump. Formally known as mega retrogressive thaw slumps, these areas superficially resemble a landslide. They’re also prone to repeat performances: as many as 90% of Canada’s Arctic slumps recur in the same place as previous slumps. Researchers used ground-penetrating radar and other tools to study the underground structure at slumps and found that several factors contribute to this repetitive cycle.

Seawater soaking into the foot of a hilly shore can destabilize the permafrost, creating a slump. That changes the nearby ground cover, exposing more permafrost to warming; their measurements showed this warming could extend tens of meters underground, priming the area for future slumps. Similarly, the mudslides and narrow ravines that form on an active slump also shift away ground cover and warm the underlying permafrost. Together, these factors suggest that once a slump forms, more slumps will occur as the underlying permafrost warms. (Image credit: M. Krautblatter; research credit: M. Krautblatter et al.; via Eos)

![Composite image of bed layers for 4 different particle density ratios. Text reads, "The wave amplitude and growth rate increase with particle density ratio but only if [the density of large particles is greater than the smaller particle density]." Composite image of bed layers for 4 different particle density ratios. Text reads, "The wave amplitude and growth rate increase with particle density ratio but only if [the density of large particles is greater than the smaller particle density]."](https://fyfluiddynamics.com/wp-content/uploads/KHbed3-1024x576.png)