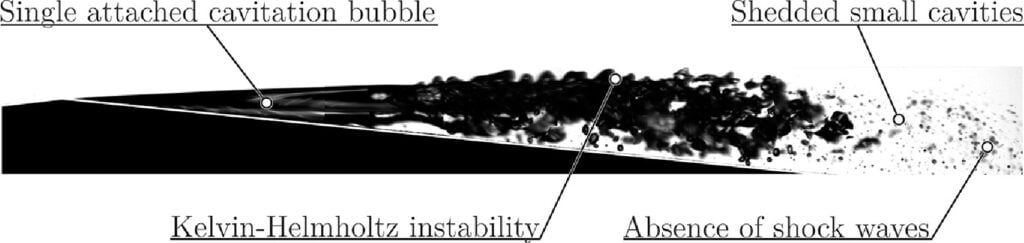

Sixty Symbols has a great new video explaining the laboratory set-up for demoing a Kelvin-Helmholtz instability. You can see a close-up from the demo above. Here the pink liquid is fresh water and the blue is slightly denser salt water. When the tank holding them is tipped, the lighter fresh water flows upward while the salt water flows down. This creates a big velocity gradient and lots of shear at the interface between them. The situation is unstable, meaning that any slight waviness that forms between the two layers will grow (exponentially, in this case). Note that for several long seconds, it seems like nothing is happening. That’s when any perturbations in the system are too small for us to see. But because the instability causes those perturbations to grow at an exponential rate, we see the interface go from a slight waviness to a complete mess in only a couple of seconds. The Kelvin-Helmholtz instability is incredibly common in nature, appearing in clouds, ocean waves, other planets’ atmospheres, and even in galaxy clusters! (Image and video credit: Sixty Symbols)