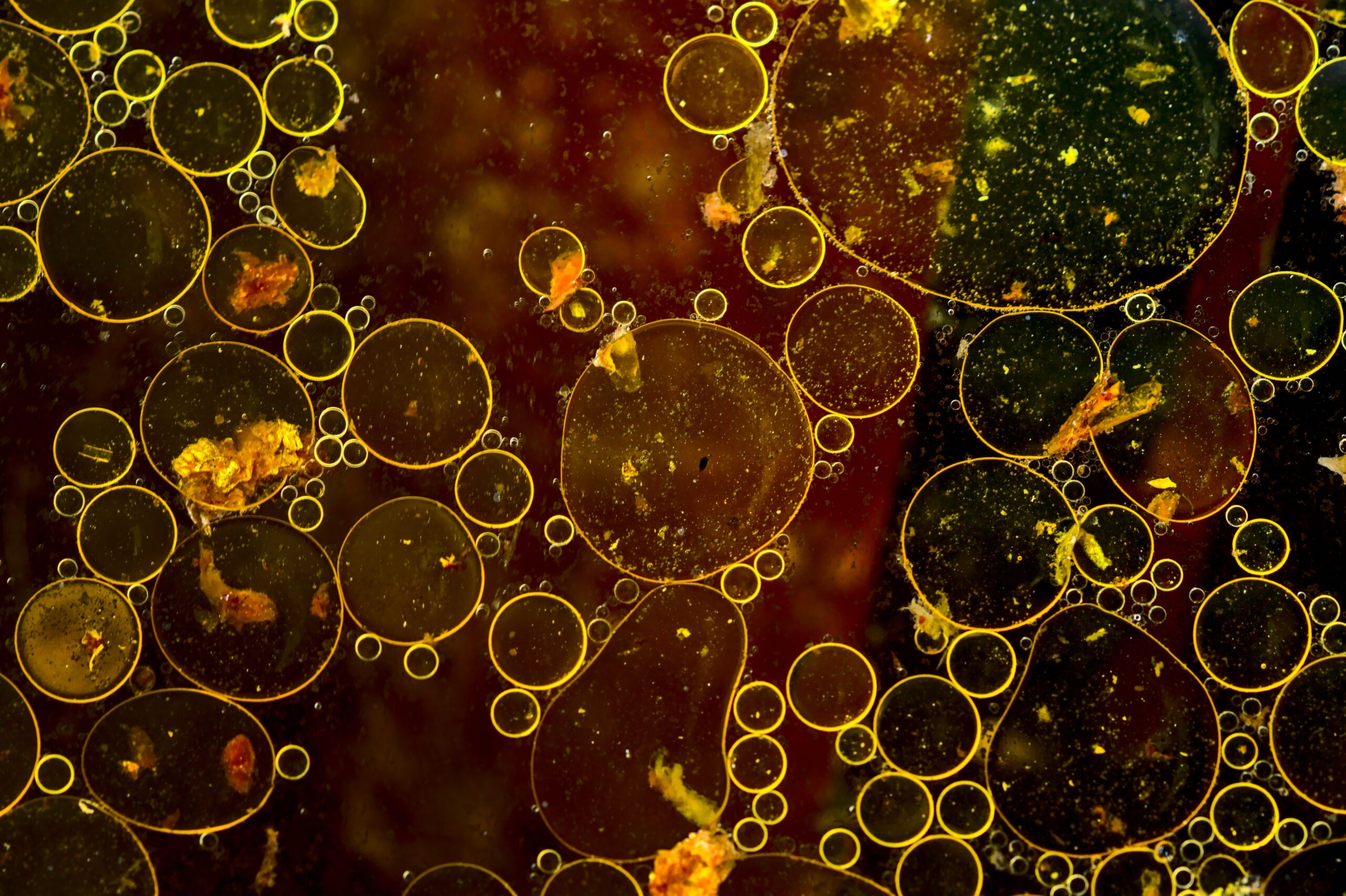

When bubbles form in magma deep below the earth, volcanic eruptions follow. Scientists believe this happens when decompression of the magma allows volatile compounds to come out of solution and form bubbles–just as opening a bottle of seltzer allows carbon dioxide to bubble out. But a new study indicates that decompression may not be the only source of bubbles.

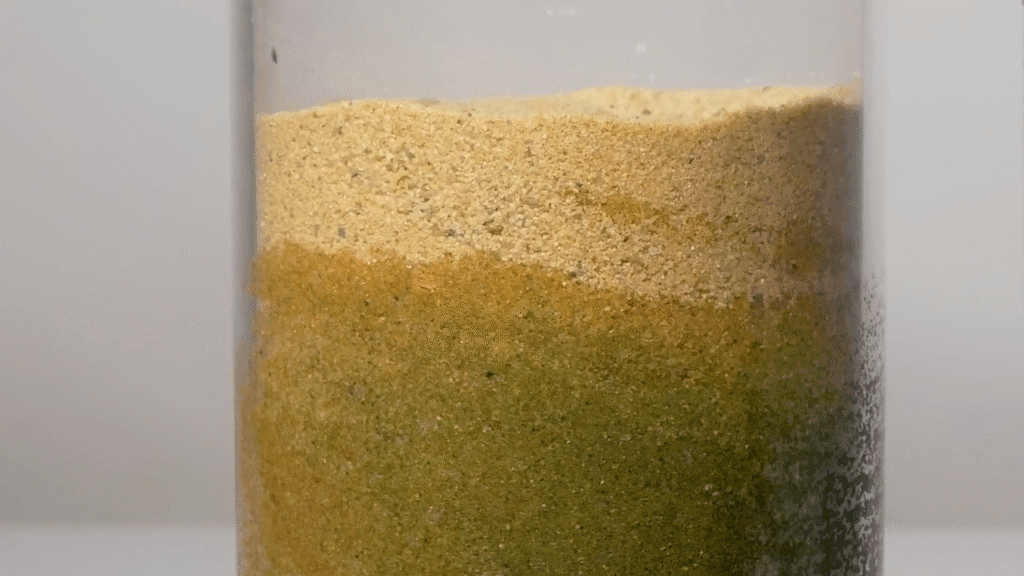

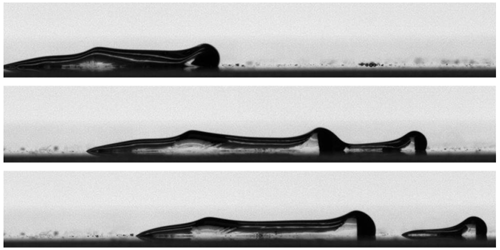

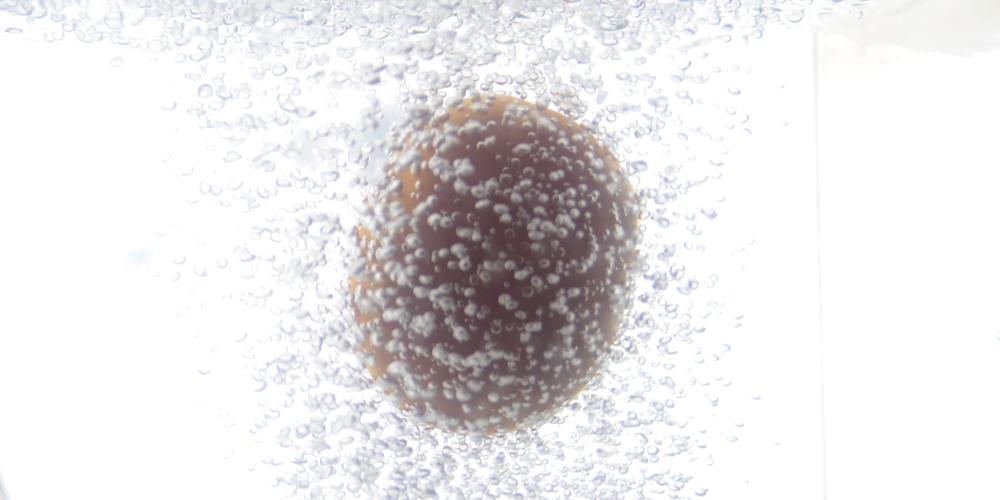

The team found that supersaturated fluids can nucleate bubbles when they’re sheared–even without decompression. They demonstrated this in the lab, not with magma but with a low-temperature magma analog, seen above. The more saturated with volatiles the fluid is, the less shear is needed to trigger bubbles.

Viscous shear is everywhere for magma, so this bubble formation mechanism is likely common. Better understanding how and when bubbles form in magma directly affects predictions for eruptions–especially for determining whether they’re likely to be explosive or effusive. (Image credit: volcano – A. Bonnerdeaux, experiment – O. Roche et al.; research credit: O. Roche et al.; via Physics World)