In April and May late autumn storms ripped through Aotearoa New Zealand. This image shows the central portion of South Island, where coastal waters are unusually bright thanks to suspended sediment. We typically think of storm run-off as water, but these flows can carry lots of sediment as well. Here, the large amount of sediment is likely a combination of increased run-off from rivers and coastal sediment stirred up by faster river flows. (Image credit: W. Liang; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Tag: flow visualization

“Now I See – The Collection Vol. 2”

In the next video of his current collection, Roman De Giuli takes us flying over liquid landscapes that look like our Earth in miniature. Many of them have the feeling of river deltas or glaciers. Sharp-eyed viewers will notice bubbles and flotsam in some of these streams. If you follow them, you can see how the flows vary — wiggling around islands, speeding up through constrictions and slowing down when the stream widens. It is, as always, a beautiful form of flow visualization. (Video and image credit: R. De Giuli)

Stunning Interstellar Turbulence

The space between stars, known as the interstellar medium, may be sparse, but it is far from empty. Gas, dust, and plasma in this region forms compressible magnetized turbulence, with some pockets moving supersonically and others moving slower than sound. The flows here influence how stars form, how cosmic rays spread, and where metals and other planetary building blocks wind up. To better understand the physics of this region, researchers built a numerical simulation with over 1,000 billion grid points, creating an unprecedentedly detailed picture of this turbulence.

The images above are two-dimensional slices from the full 3D simulation. The upper image shows the current density while the lower one shows mass density. On the right side of the images, magnetic field lines are superimposed in white. The results are gorgeous. Can you imagine a fly-through video? (Image and research credit: J. Beattie et al.; via Gizmodo)

Clapping Hands

Although often associated with applause, hand clapping is more universal than that. The distinctive sound can mark rhythms, draw attention, and even test the surrounding acoustics. But how exactly does hand clapping work? A recent study shows that the acoustics of hand clapping come from more than just the collision of hands. Especially in a cupped configuration, clapping hands act like a Helmholtz resonator (think blowing across a bottle top), producing a resonant jet that squeezes out between the forefinger and thumb of the impacted hand. Check out the images above to see how that jet appears in various clapping configurations. (Image and research credit: Y. Fu et al.; via Physics Today)

Melting in a Spin

The world’s largest iceberg A23a is spinning in a Taylor column off the Antarctic coast. This poster looks at a miniature version of the problem with a fluorescein-dyed ice slab slowly melting in water. On the left, the model iceberg is melting without rotating. The melt water stays close to the base until it forms a narrow, sinking plume. In the center, the ice rotates, which moves the detachment point outward. The wider plume is turbulent compared to the narrow, non-rotating one. At higher rotation speeds (right), the plume is even wider and more turbulent, causing the fastest melting rate. (Image credit: K. Perry and S. Morris)

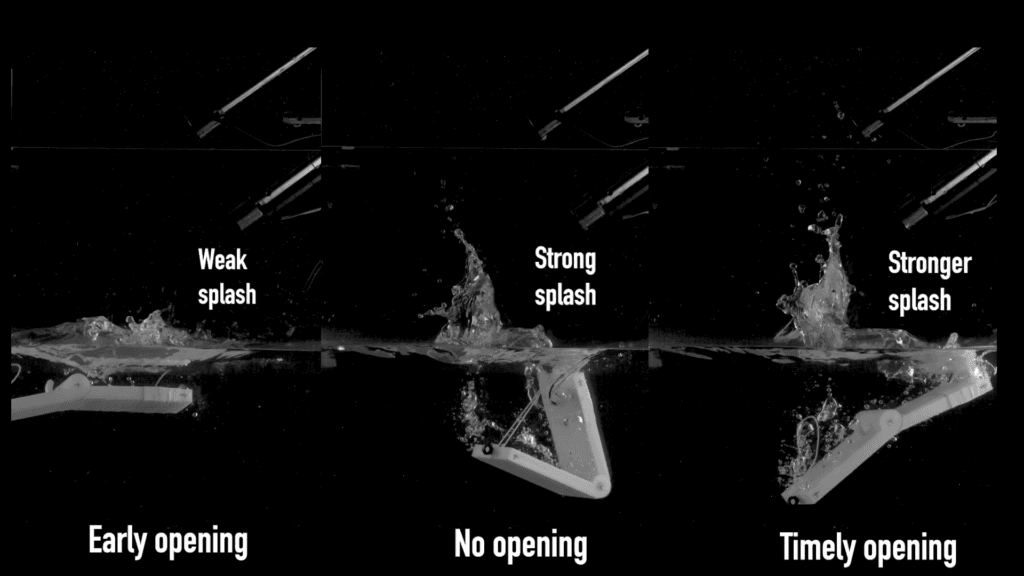

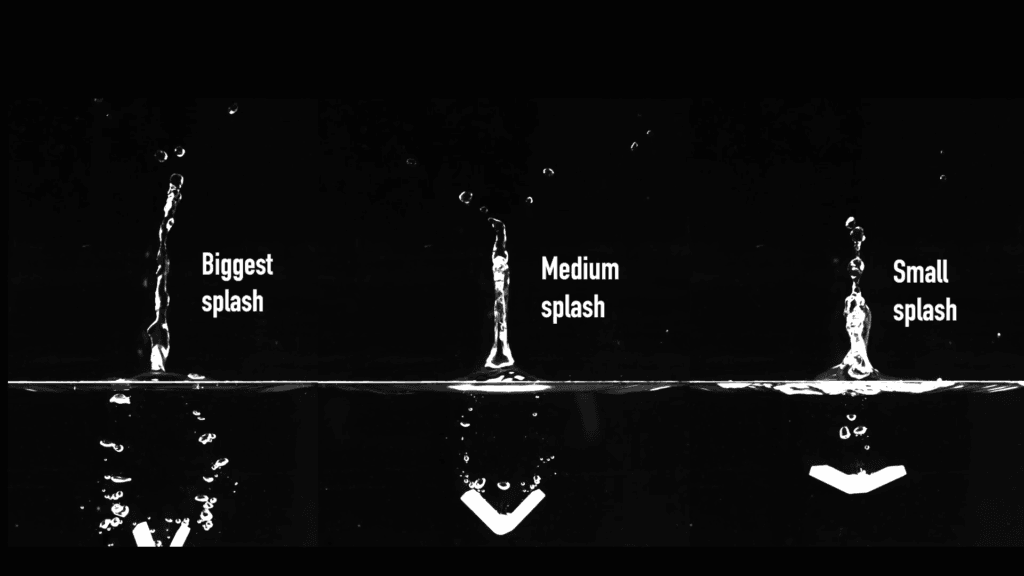

Manu Jumping, a.k.a. How to Make a Big Splash

The Māori people of Aotearoa New Zealand compete in manu jumping to create the biggest splash. Here’s a fun example. In this video, researchers break down the physics of the move and how it creates an enormous splash. There are two main components — the V-shaped tuck and the underwater motion. At impact, jumpers use a relatively tight V-shape; the researchers found that a 45-degree angle works well at high impact speeds. This initiates the jumper’s cavity. Then, as they descend, the jumper unfolds, using their upper body to tear open a larger underwater cavity, which increases the size of the rebounding jet that forms the splash. To really maximize the splash, jumpers can aim to have their cavity pinch-off (or close) as deep underwater as possible. (Video and image credit: P. Rohilla et al.)

Flamingo Fluid Dynamics, Part 2: The Game’s a Foot

Yesterday we saw how hunting flamingos use their heads and beaks to draw out and trap various prey. Today we take another look at the same study, which shows that flamingos use their footwork, too. If you watch flamingos on a beach, in muddy waters, or in a shallow pool, you’ll see them shifting back and forth as they lift and lower their feet. In humans, we might attribute this to nervous energy, but it turns out it’s another flamingo hunting habit.

As a flamingo raises its foot, it draws its toes together; when it stomps down, its foot spreads outward. This morphing shape, researchers discovered, creates a standing vortex just ahead of its feet — right where it lowers its head to sample whatever hapless creatures it has caught in this swirling vortex. And the vortex, as shown below, is strong enough to trap even active swimmers, making the flamingo a hard hunter to escape. (Image credit: top – L. Yukai, others – V. Ortega-Jimenez et al.; research credit: V. Ortega-Jimenez et al.; submitted by Soh KY)

Flamingo Fluid Dynamics, Part 1: A Head in the Game

Flamingos are unequivocally odd-looking birds with their long skinny legs, sinuous necks, and bent L-shaped beaks. They are filter-feeders, but a new study shows that they are far from passive wanderers looking for easy prey in shallow waters. Instead, flamingos are active hunters, using fluid dynamics to draw out and trap the quick-moving invertebrates they feed on. In today’s post, I’ll focus on how flamingos use their heads and beaks; next time, we’ll take a look at what they do with their feet.

Feeding flamingos often bob their heads out of the water. This, it turns out, is not indecision, but a strategy. Lifting its flat upper forebeak from near the bottom of a pool creates suction. That suction creates a tornado-like vortex that helps draw food particles and prey from the muddy sediment.

When feeding, flamingos will also open and close their mandibles about 12 times a second in a behavior known as chattering. This movement, as seen in the video above, creates a flow that draws particles — and even active swimmers! — toward its beak at about seven centimeters a second.

Staying near the surface won’t keep prey safe from flamingos, either. In slow-flowing water, the birds will set the upper surface of their forebeak on the water, tip pointed downstream. This seems counterintuitive, until you see flow visualization around the bird’s head, as above. Von Karman vortices stream off the flamingo’s head, which creates a slow-moving recirculation zone right by the tip of the bird’s beak. Brine shrimp eggs get caught in these zones, delivering themselves right to the flamingo’s mouth.

Clearly, the flamingo is a pretty sophisticated hunter! It’s actively drawing out and trapping prey with clever fluid dynamics. Tomorrow we’ll take a look at some of its other tricks. (Image credit: top – G. Cessati, others – V. Ortega-Jimenez et al.; research credit: V. Ortega-Jimenez et al.; submitted by Soh KY)

“Soap Bubble Bonanza

This video offers an artistic look at a soap bubble bursting. The process is captured with high-speed video combined with schlieren photography, a technique that makes visible subtle density variations in the air. The bubbles all pop spontaneously, once enough of their cap drains or evaporates away for a hole to form. That hole retracts quickly; the acceleration of the liquid around the bubble’s spherical shape makes the retracting film break into droplets, seen as falling streaks near the bottom of the bubble. The retraction also affects air inside the bubble, making the air that touched the film curl up on itself, creating turbulence. Then, as the film completes its retraction, it pushes a plume of the once-interior air upward, as if the interior of the bubble is turning itself inside out. (Video and image credit: D. van Gils)

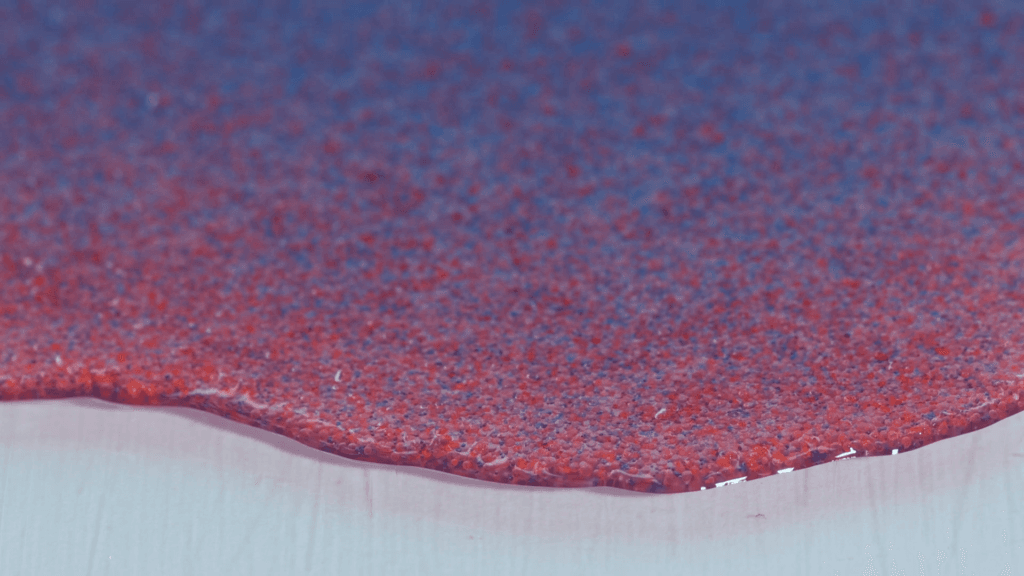

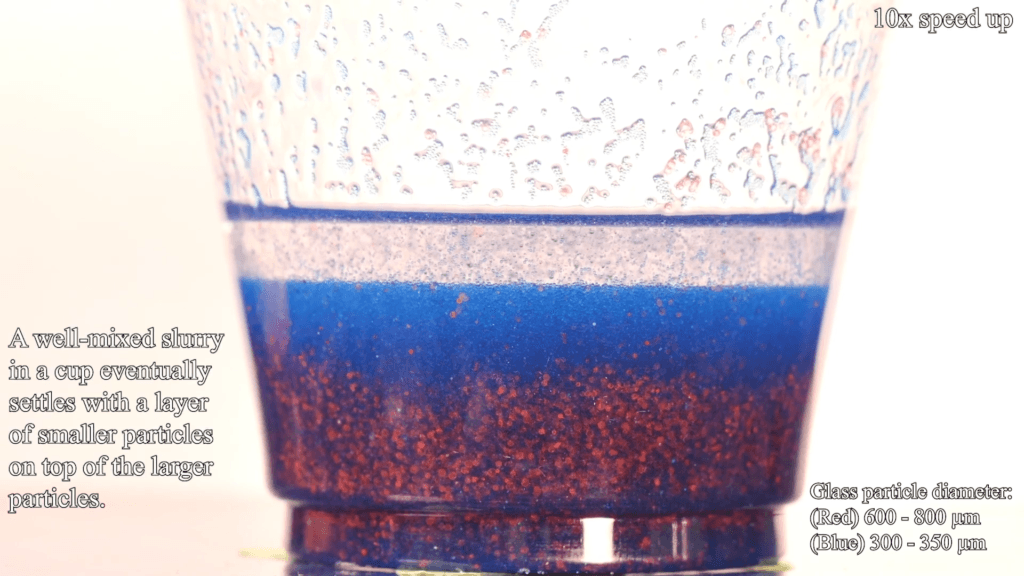

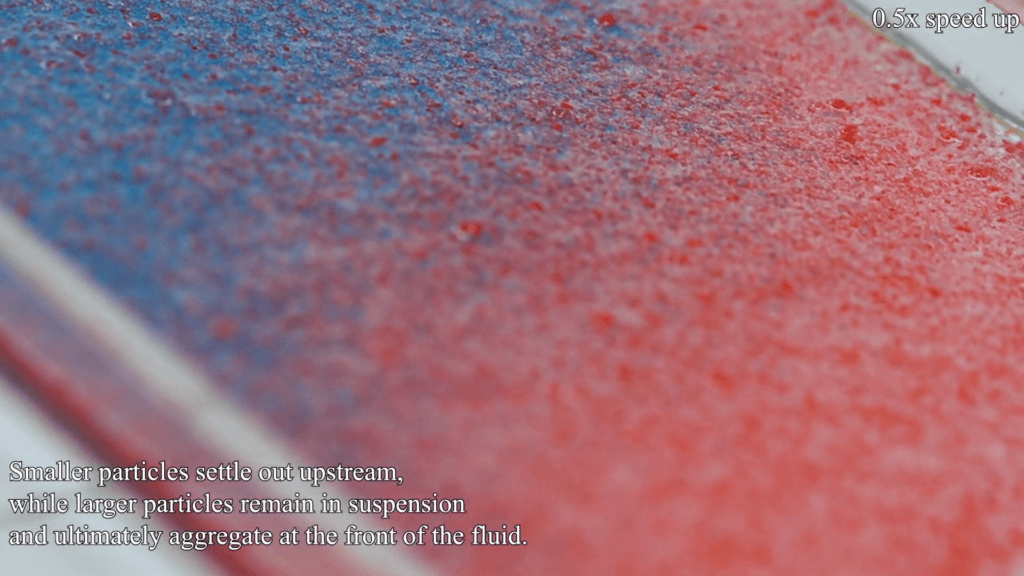

Bigger Particles Slide Farther

Mudslides and avalanches typically carry debris of many shapes and sizes. To understand how debris size affects flows like these, researchers use simplified, laboratory-scale experiments like this one. Here, researchers mix a slurry of silicone oil and glass particles of roughly two sizes. The red particles are larger; the blue ones smaller. Sitting in a cup, the mixture tends to separate, with red particles sinking faster to form the bottom layer and smaller blue particles collecting on top. And what happens when such a mixture flows down an incline? The smaller blue particles tend to settle out sooner, leaving the larger red particles in suspension as they flow downstream. (Video and image credit: S. Burnett et al.)