Inside a combustion chamber, temperature fluctuations can cause sound waves that also disrupt the flow, in turn. This is called a thermoacoustic instability. In this video, researchers explore this process by watching how flames move down a tube. The flame fronts begin in an even curve that flattens out and then develops waves like those on a vibrating pool. Those waves grow bigger and bigger until the flame goes completely turbulent. Visually, it’s mesmerizing. Mathematically, it’s a lovely example of parametric resonance, where the flame’s instability is fed by system’s natural harmonics. (Video and image credit: J. Delfin et al.; research credit: J. Delfin et al. 1, 2)

Tag: flame

Searching for Stability in Cleaner Flames

Spiking natural gas power plants with hydrogen could help them burn cleaner as we transition away from carbon power. But burners in power plants and jet engines can be extremely finicky, thanks to thermoacoustic instabilities. As a flame burns, it can sputter and fluctuate in its heat output. That creates pressure oscillations (which we sometimes hear as sound waves) that reflect off the burner’s walls and return toward the flame, causing further fluctuations. This feedback loop can be destructive enough to explode combustion chambers.

Adding hydrogen to a burner designed purely for natural gas can trigger these instabilities (above image), but researchers hope that by exploring fuel-mixtures and their effect at lab-scale, they can help designers find safe ways to adapt industrial burners for the cleaner fuel mixture. (Image and research credit: B. Ahn et al.; via APS Physics)

Exciting a Flame in a Trough

A viewer sent Steve Mould his accidental discovery of this odd flame behavior. In these 3D-printed troughs, a flame lit in lighter fluid will rocket around the track repeatedly as it burns the local supply of gaseous lighter fluid. As Steve shows in his video, this system is an excitable medium and the trick works for a whole array of 3D-printed shapes. Check out the full video above. (Video and image credit: S. Mould)

A Colorful Fire Tornado

This one definitely belongs in the do-not-try-this-yourself category, but this Slow Mo Guys video of a colorful fire tornado is pretty spectacular. Using an array of different fuels and a ring of box fans, Gav sets up a vortex of flame that transitions smoothly from red all the way to blue. As he points out in the video, the translucency of the vortex is so good that you can see how the two sides of the vortex rotate! (Video credit: The Slow Mo Guys)

Cleaning Up Combustion

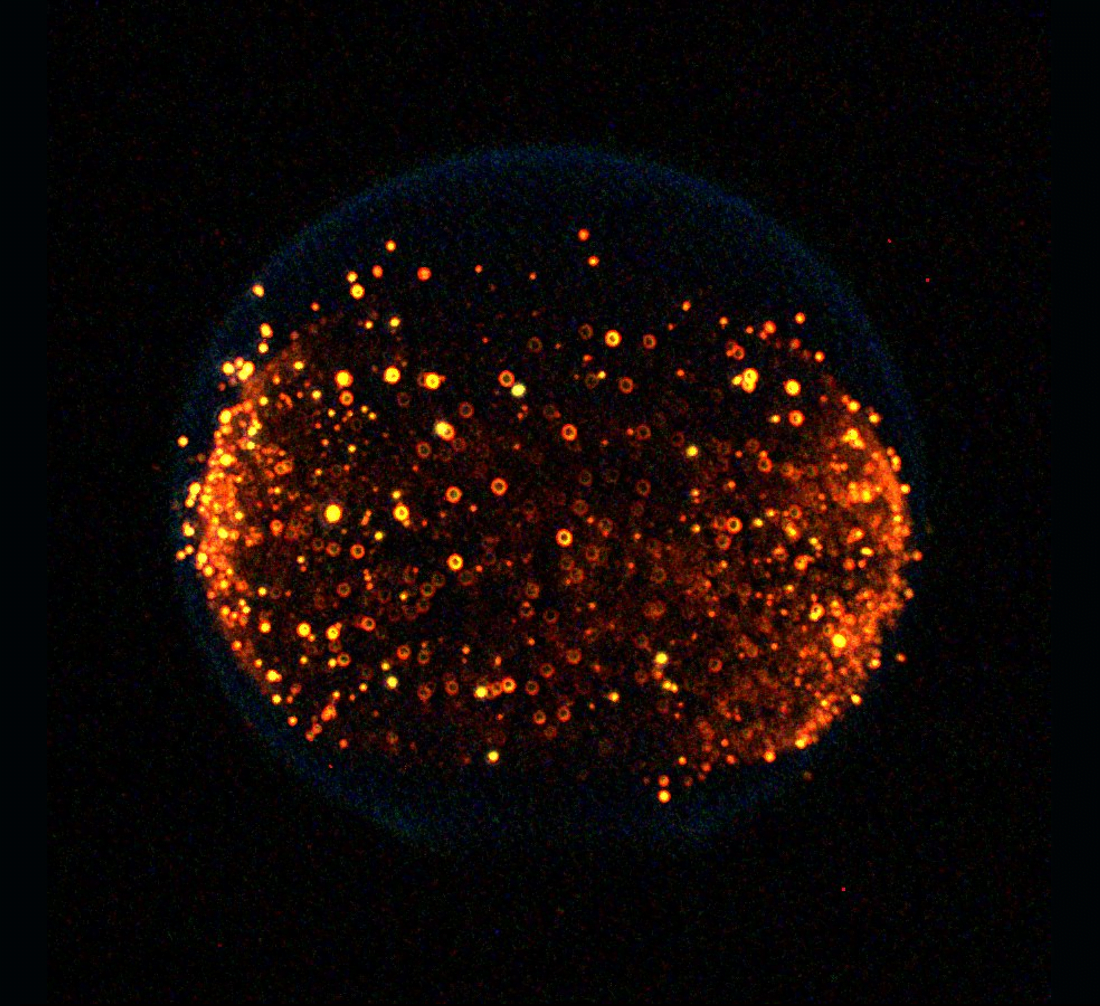

In space, flames behave quite differently than we’re used to on Earth. Without gravity, flames are spherical; there are no hot gases rising to create a teardrop-shaped, flickering flame. In many ways, removing gravity makes combustion simpler to study and allows scientists to focus on fundamental behaviors. It’s no surprise, then, that combustion experiments are a long-standing feature on the International Space Station.

In the photo above, we see a flame in microgravity studded with bright yellow spots of soot. Soot is a by-product of incomplete combustion; it’s essentially unburned leftovers from the chemical reaction between fuel and oxygen. In this experiment, researchers were studying how much soot is produced under different burning conditions, work that will help design flames that burn more cleanly in the future. (Image and video credit: NASA; submitted by @LordDewi)

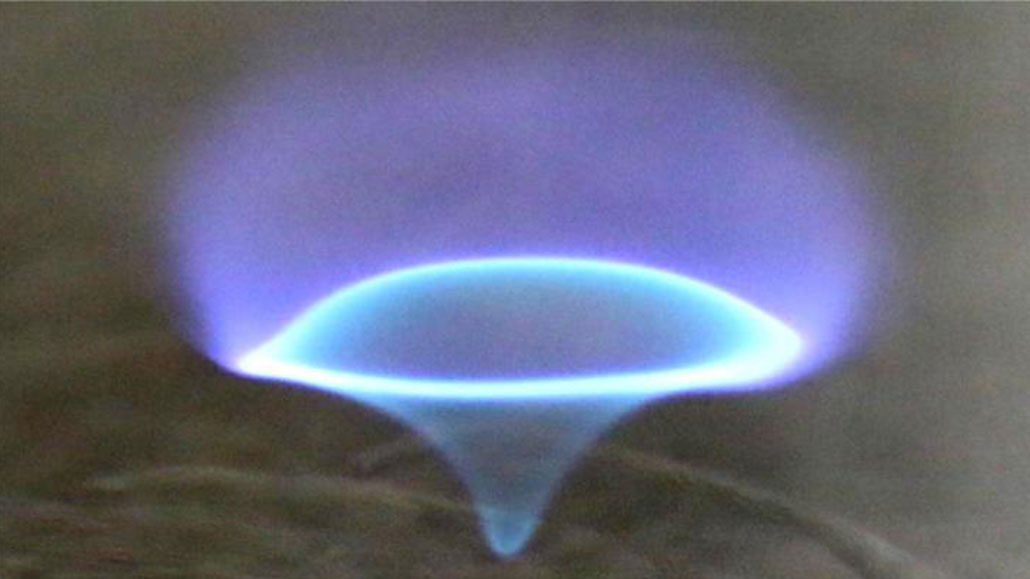

The Structure of the Blue Whirl

Several years ago, researchers discovered a new type of flame, the blue whirl. Now computational simulations have helped them untangle the complex structure of this clean-burning flame. Their work shows that the blue whirl is made up of three types of flames, which meet to form a fourth.

The conical base of the whirl is a fuel-rich flame in which the fuel and oxygen are initially well-mixed. Above that is a diffusion flame, where the fuel and oxygen are initially separate and the flame’s ability to burn is limited by how readily the two mix. Along the sides of the blue whirl is a third flame type, visible only as a faint wisp. Like the first flame, this one is premixed, but it contains much less fuel than oxygen. Finally, those three flames meet in the bright blue ring of the whirl, where the ratio of fuel and oxygen is just right to burn the fuel completely. (Image and research credit: J. Chung et al.; via Science News; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Fractal Flame Propagation

Hydrogen is a promising alternative to carbon-based fuels, but it comes with its own special challenges. Hydrogen gas is extremely flammable, including under circumstances that would normally quench flames, as shown in this recent study.

What you see above are water condensation patterns left behind after the passage of hydrogen flames through a narrow gap between two glass plates. With other fuels, the narrow confinement and low fuel ratio used in these experiments would keep the flames from spreading. But because hydrogen is so light, it diffuses much faster than other fuels, allowing it to spread in these fractal patterns despite its confinement. Engineers will have to account for hydrogen’s easy spread when designing containment strategies. (Image and research credit: F. Veiga-López et al.; via APS Physics)

Understanding Wildfire

Wildfires are an ongoing challenge in the western United States, where droughts and warmer conditions have combined with a century of fire suppression to form perfect conditions for monstrous fires. It’s long been understood that ambient winds can drive spreading fire, but the connection between wildfire and wind is more complicated than this.

The heat of a fire drives buoyant air to rise, creating tower-like updrafts in a flame front. We see this both in the shape of the grass fire above, and in the wind vectors of a simulated grass fire in the lower image. Between those towers are troughs where cooler ambient wind is drawn in to replace the rising air. How a fire spreads will depend on the speed, direction, and temperature of these winds. A hot wind fed by the fire’s heat will raise the temperature of fuel in unburned areas, bringing it closer to ignition. In contrast, cooler ambient winds can hinder a fire by keeping nearby grass and twigs too cool to ignite. (Image credit: fire – M. Finney/US Forest Service; simulation – R. Linn; research credit: R. Linn et al.; for more, see Physics Today)

Streaming Fire

I’m just going to start this one with a blanket statement: DO NOT TRY THIS. Instead, enjoy the fact that the Internet enables us to enjoy the sight of burning gasoline in slow mo without any danger to ourselves.

In this video, Gav and Dan capture a burning bucket of gasoline as it’s thrown against glass. One thing this stunt really highlights is that it’s not the liquid gasoline that burns, it’s the vapor. However, since gasoline is volatile – in other words, it evaporates easily – the fire is quick to spread, especially as the toss atomizes droplets near the edge of the fluid. That’s why you see distinct streaks near the edge of the spreading flame and a non-burning liquid in the center. (Image and video credit: The Slow Mo Guys)

The Beauty of Flames

The flickering yellow and orange flames most of us are used to thinking of are rather different from the flames researchers study. In this video, the Beauty of Science team offers a short primer on different flame shapes studied in combustion, including laminar, swirling, and jet flames. Each has its own distinctive character and may be advantageous or not, depending on the application for the flame. A laminar flame, for example, is steady, which might make it a good choice for something like a Bunsen burner, where consistency is needed. Whereas a turbulent flame is better capable of mixing fuel and oxidizer, which is key in applications like rocket engines, where that mixing can be a limiting factor in the engine’s efficiency. (Image and video credit: Beauty of Science)