Fans of sci-fi and fantasy have a long-standing tradition of exploring the physics and/or practicality of creations in their fandom, and Star Wars fans are no exception. Here engineers ask whether Luke Skywalker’s X-wing fighter could survive the descent through Dagobah’s atmosphere as he searched for Master Yoda. Their results are based on a numerical simulation, with some assumptions about the spacecraft’s descent path and design as well as the planet’s atmosphere. Fans of the Jedi will be glad to hear that the X-wing can survive its supersonic descent intact, delivering the last Jedi safely to his mentor. (Image credit: Y. Ling et al.)

Tag: computational fluid dynamics

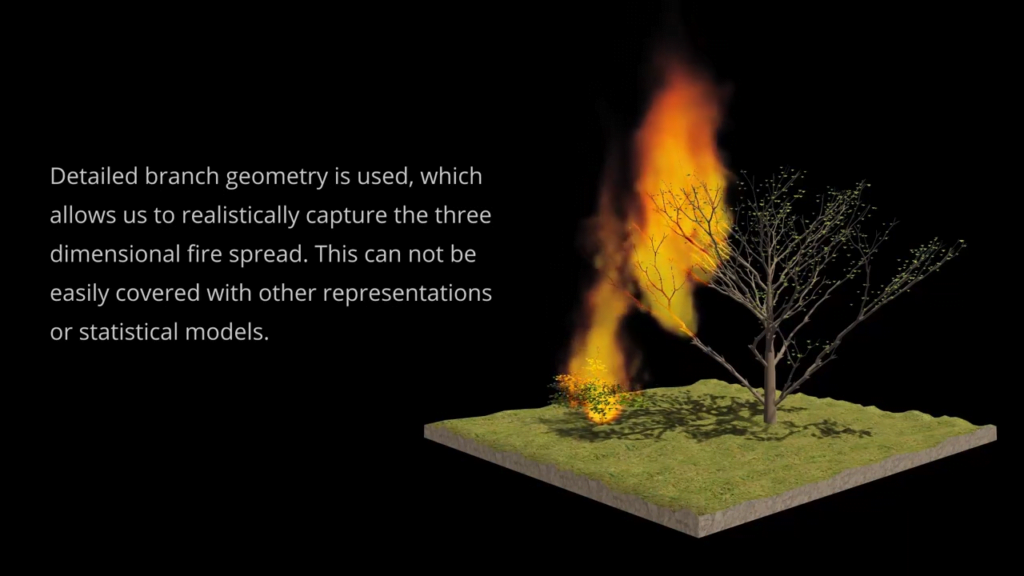

Burning Virtual Forests

Wildfires are growing ever more frequent and more destructive as the climate crisis worsens. Unfortunately, simulating and predicting the course of these fires is incredibly difficult, requiring a combination of ecology, meteorology, combustion science, and more. To handle so many variables, model builders often turn to statistics that allow them to simulate an entire forest but at the cost of representing individual trees as a few pixels or a cone.

In this video, researchers show a new wildfire simulation based on a computationally efficient but more realistic depiction of trees. With individual, three-dimensional trees, the simulation can capture effects that are otherwise hard to examine – like the difference in burn rate for coniferous and deciduous forests and the likelihood that a fire can jump a firebreak of a given size. Their weather, fire, and atmospheric models are even able to simulate the birth of fire-generated clouds! Check out the full video to see more and then head over to their site if you’d like to dig into the methodology. (Video and research credit: T. Hädrich et al.; see also)

Mountains in the Sky

Our skies can sometimes presage the weather to come. In thunderstorms, a cirrus plume above an anvil cloud will often appear (visible by satellite) about half an hour before severe conditions are reported on the ground. A new study delves into the origins of these plumes and finds that they result from an internal hydraulic jump in the storm that acts a bit like an artificial mountain, driving air — and the moisture it contains — higher in the stratosphere than normal. Once the jump is established, the authors found it could drive 7 tonnes per second of water vapor into the stratosphere! (Image credit: jplenio; research credit: M. O’Neill et al.; via Science)

Marshland Wave Damping

Coastal marshes are a critical natural defense against flooding. The flexible plants of the marsh both slow the water’s current and help damp waves. As a result of that hydrodynamic dissipation, marshes help protect against erosion and reduce the magnitude of flooding events. But coastal managers looking to maintain or improve their marshes in order to mitigate climate-change-driven storms need to be able to predict what level of vegetation they need.

To that end, a team of researchers has built a new model to better capture the flow effects of marsh grasses. Building from an individual, flexible plant (as opposed to a rigid cylinder, as grass is often represented), the authors constructed a model able to predict wave dissipation for many marsh configurations, which should help better predict the infrastructure changes needed in different coastal regions. (Image credit: T. Marquis; research credit: X. Zhang and H. Nepf; via APS Physics)

Superfluid Instabilities

Superfluids — like Bose-Einstein condensates — are bizarre compared to fluids from our everyday experience because they have no viscosity. Without viscosity, it’s no surprise that they behave in unusual ways. Here, researchers simulated superfluids moving past one another. In each of these images, the blue fluid is moving to the left, and the red fluid is moving to the right. In a typical fluid, such motion causes ocean-wave-like curls due to the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability.

Instead, with a low relative velocity and high repulsion between atoms of the two layers, the superfluids form a tilted, finger-like interface (Image 1) that the authors refer to as a flutter-finger pattern. (Repulsion essentially sets the miscibility between the superfluids. With a high repulsion, the superfluids resist mixing.)

With a higher relative velocity (Image 2), the wavelength of the ripples becomes comparable to the thickness of the interface, and the superfluids take on a very different, zipper-like pattern. Note how the tips detach and reconnect to the neighboring finger!

With lower repulsion, the interface between the two liquids is thicker and breaks down quickly (Image 3). The authors call this a sealskin pattern. (Image credits: water – M. Blažević, simulations – H. Kokubo et al.; research credit: H. Kokubo et al.; via APS Physics)

Better Inhalers Through CFD

As levels of air pollution rise, so does the incidence of pulmonary diseases like asthma. Treatments for these diseases largely rely on inhalers containing drug particles that need to be carried into the small bronchi of the lungs. To better understand how the process works, researchers used computational fluid dynamics to simulate how air and particles travel through the human respiratory tract.

The team found that larger particles tended to get stuck in the mouth instead of making it down into the lungs. This problem was made worse at high inhalation rates because the particles’ inertia was too large for them to make the sharp turn down into the trachea. In contrast, smaller particles could travel down into the lungs and into the smaller branches there before settling. The authors concluded that inhalers should use fine drug particles to maximize delivery into the lungs. They also note that adjusting inhalers to deliver more medication to the lungs may also lower the overall price because less of the dosage gets wasted in the patient’s mouth.

Of course, the study’s results also serve as a warning about the dangers of air pollution from fine particulates. Here in Colorado, our summers are punctuated with wildfire smoke, much of it in the form of tiny particles about the same size as the drug particles in this study. If fine drug particles are effective at making it into the smaller branches of our lungs, so are those pollutants. That’s a good reason to stay inside in smoky conditions or use a high-quality N-95 mask while out and about. (Image credit: coltsfan; research credit: A. Tiwari et al.; via Physics World; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Stingray Eyes

With their flexible, flattened shape, rays are some of the most efficient swimmers in the ocean. But, at first glance, it seems as if their protruding eyes and mouth would interfere with that streamlining. A new study uses computational fluid dynamics to tackle the effects of these protrusions on stingray hydrodynamics.

With their digital stingrays, the team found that the animal’s eyes and mouth created vortices that accelerated flow over the front of the ray and increased the pressure difference across its top and bottom surfaces. The result was better thrust and the ability to cruise at higher speeds. Overall, the ray’s eyes and mouth increased its hydrodynamic efficiency by more than 20.5% and 10.6%, respectively. The lesson here: looks can be deceiving when it comes to hydrodynamics! (Image credit: D. Clode; research credit: Q. Mao et al.)

Keeping Cool in the Cretaceous

I love that fluid dynamics can bring new insights to other subjects, like this study on how heavily-armored ankylosaurs avoided heat stroke. Scans of ankylosaur skulls show a complicated, twisty nasal cavity that researchers likened to a child’s crazy straw. Using numerical simulations, they showed that the airflow through these passages acts like a heat exchanger. As air gets drawn into its body, it warms up from exposure to blood vessels lining the nasal cavity; that means that, simultaneously, the hot blood is getting cooled. Those blood vessels lead up to the animal’s brain, indicating that these twisted cavities essentially serve as air-conditioning for the sauropod’s brain! (Image and video credit: Scientific American; research credit: J. Bourke et al.; via J. Ouellette)

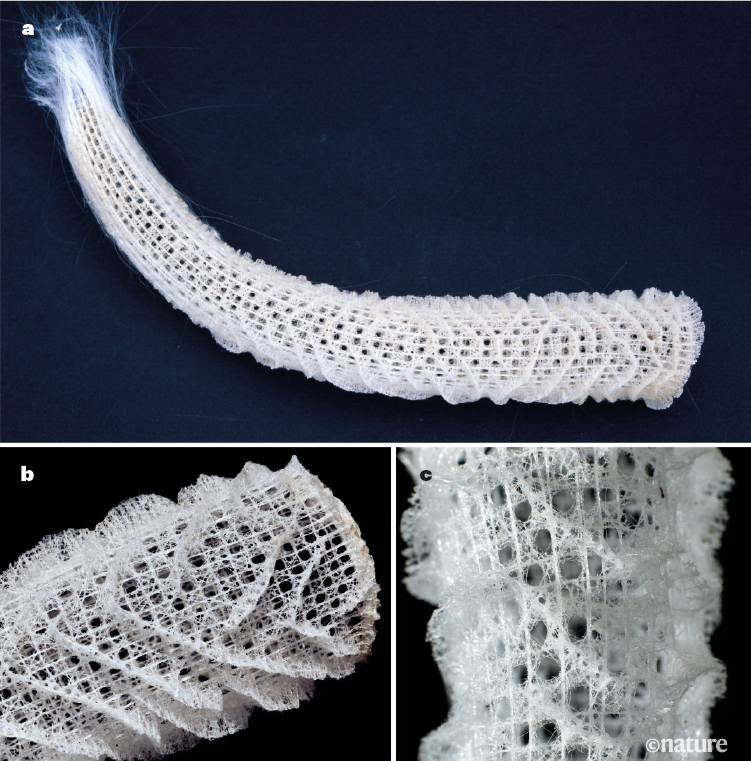

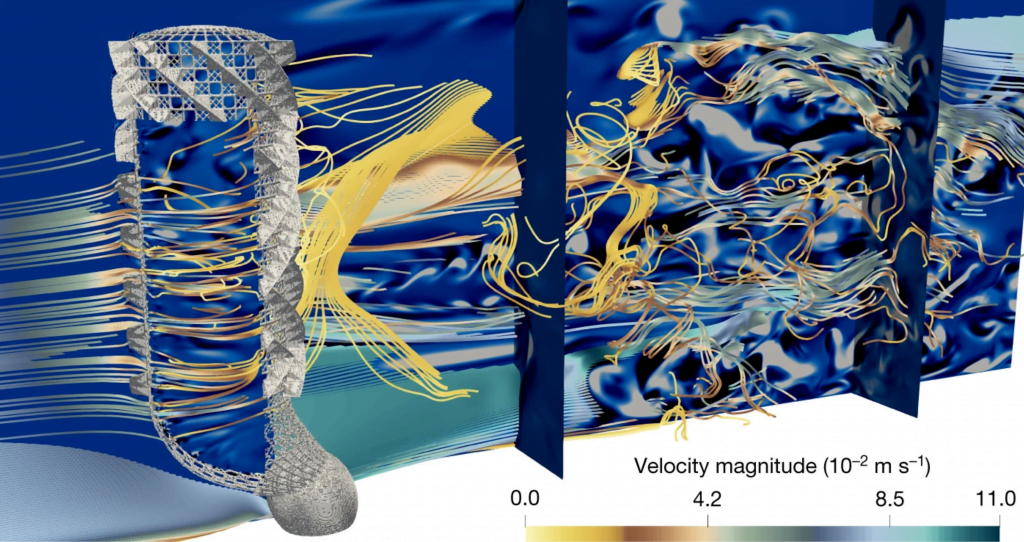

Sea Sponge Hydrodynamics

The Venus’s flower basket is a sea sponge that lives at depths of 100-1000 meters. Its intricate latticework skeleton has long fascinated engineers for its structural mechanics, but a new study shows that the sponge’s shape benefits it hydrodynamically as well.

The sea sponge’s skeleton is predominantly cylindrical, with tiny gaps that allow water to flow through it and helical ridges alongside its outer surface to strengthen it against the deep-sea currents surrounding it. Through detailed numerical simulations, researchers found that both of these features — the holes and the ridges — serve fluid mechanical purposes for the sponge. The porous holes of the sea sponge drastically reduce flow in the sponge’s wake (third image), which provides major drag reduction for the sea sponge. That drag reduction makes it easier for the sponge to stay rooted to the ocean floor.

The helical ridges, on the other hand, create low-speed vortices within the sea-sponge’s body cavity (second image). Such vortices increase the time water spends inside the sponge, likely helping it to filter-feed more efficiently. The additional vorticity comes at the cost of slightly increased drag but not enough to outweigh the savings from its porosity. (Image and research credit: G. Falcucci et al.; via Nature; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Controlling Aerosols Onstage

Few industries saw more disruption from the pandemic than the performing arts. To help orchestras return to the concert hall in a way that keeps performers and audience members safe, researchers have simulated air flow and aerosols around musicians onstage. Some instruments — like the trumpet — are super-spreaders when it comes to aerosol production, and, in the conventional organization of orchestras, those aerosols have to travel through other sections of the orchestra before reaching air vents, putting more musicians at risk.

(Upper row) Aerosol concentration for the orchestra’s original seating arrangement (left) and in the modified arrangement (right). (Bottom row) Time-averaged concentration of aerosol particles in the breathing zone of each musician in the original (left) and modified arrangements (right). Using Large Eddy Simulation, researchers looked at alternate seating arrangements for the Utah Symphony that could mitigate these risks. By rearranging the musicians so that instruments that produce lots of aerosols are closer to the air vents and open doors, the team reduced the average concentration of aerosols around musicians by a factor of 100, giving the performers a chance to return to the stage far more safely. (Image credit: top – M. Nägeli, simulation – H. Hedworth et al.; research credit: H. Hedworth et al.; via NYTimes; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)