Yesterday we saw how hunting flamingos use their heads and beaks to draw out and trap various prey. Today we take another look at the same study, which shows that flamingos use their footwork, too. If you watch flamingos on a beach, in muddy waters, or in a shallow pool, you’ll see them shifting back and forth as they lift and lower their feet. In humans, we might attribute this to nervous energy, but it turns out it’s another flamingo hunting habit.

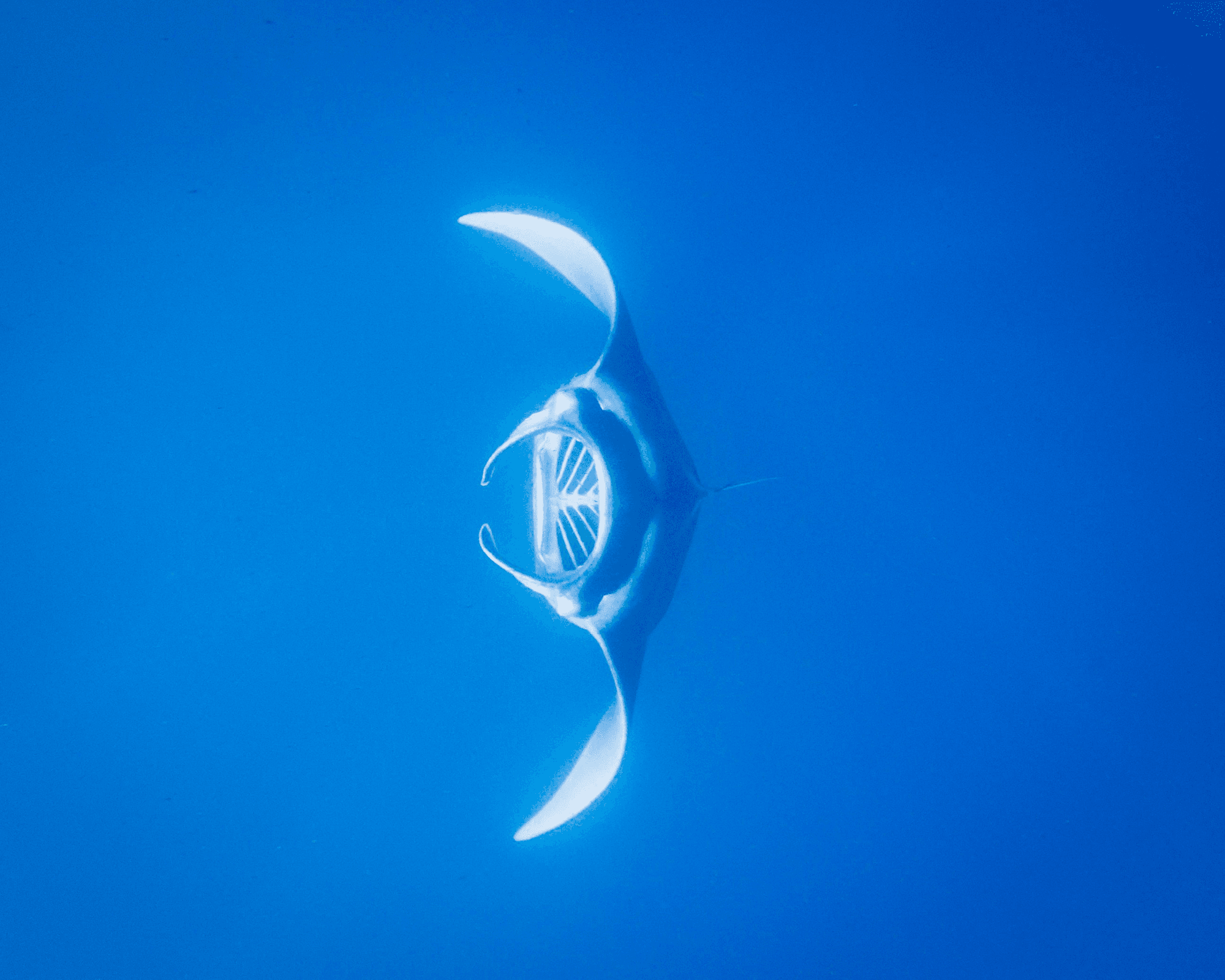

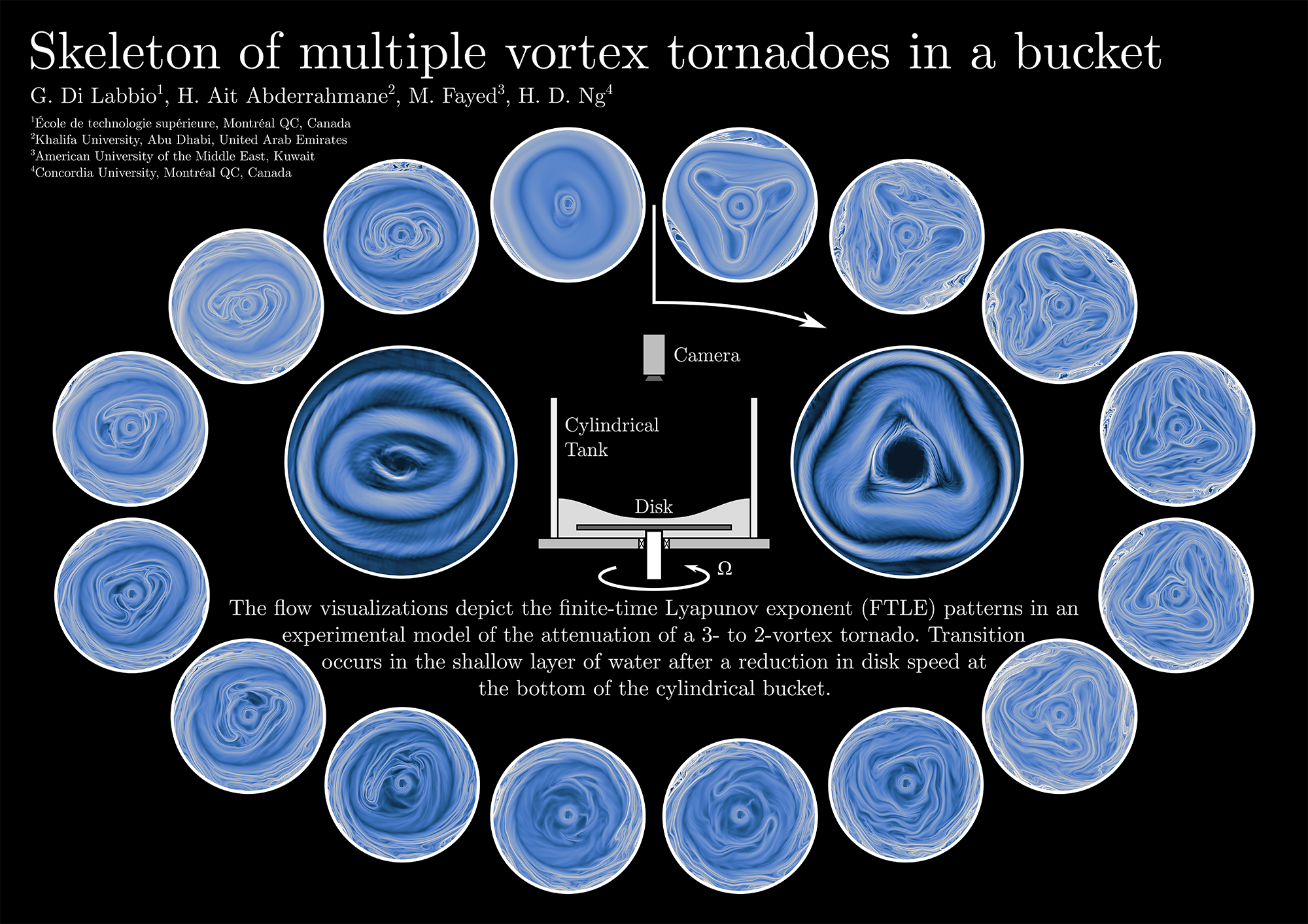

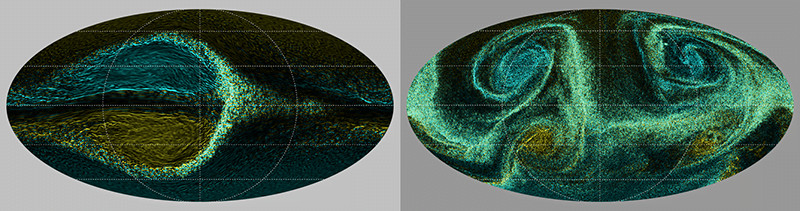

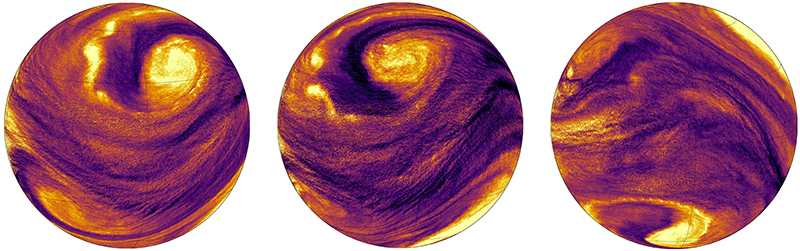

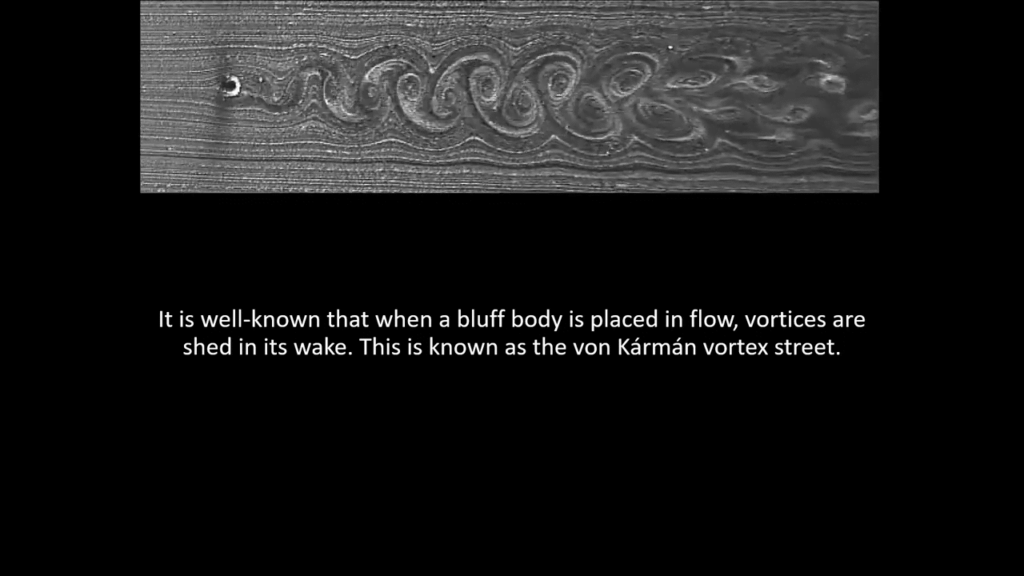

As a flamingo raises its foot, it draws its toes together; when it stomps down, its foot spreads outward. This morphing shape, researchers discovered, creates a standing vortex just ahead of its feet — right where it lowers its head to sample whatever hapless creatures it has caught in this swirling vortex. And the vortex, as shown below, is strong enough to trap even active swimmers, making the flamingo a hard hunter to escape. (Image credit: top – L. Yukai, others – V. Ortega-Jimenez et al.; research credit: V. Ortega-Jimenez et al.; submitted by Soh KY)