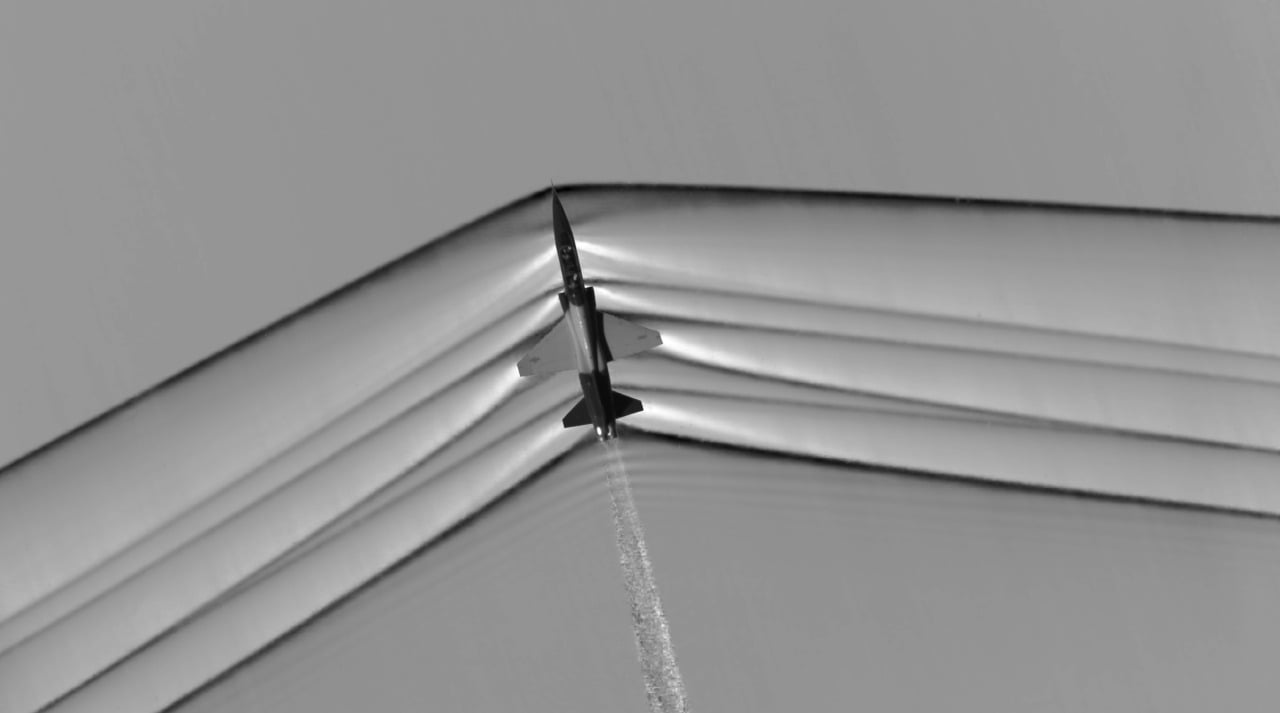

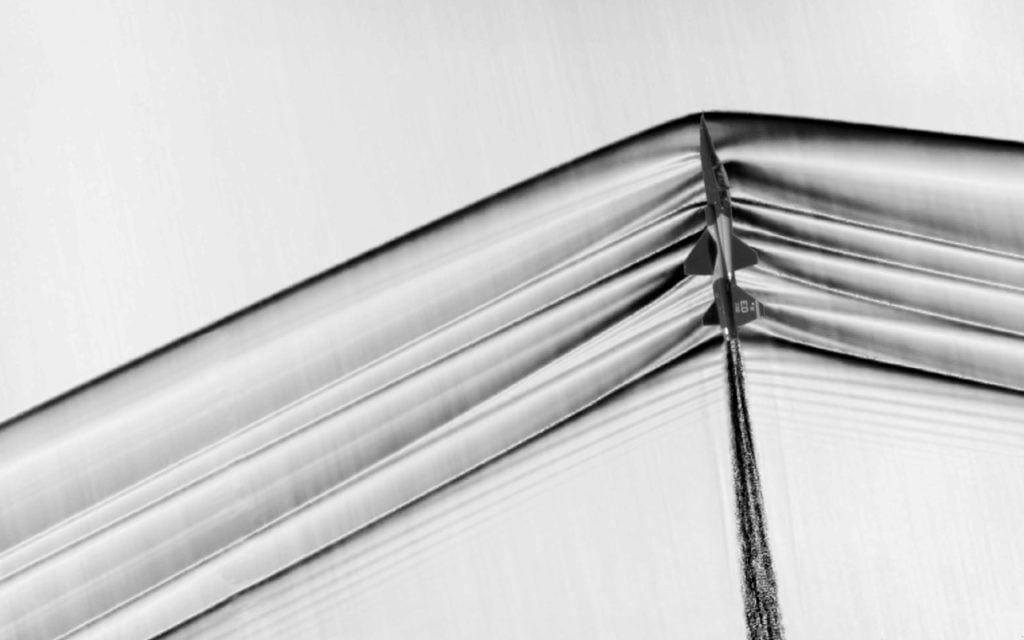

Schlieren optical systems have been used to visualize shock waves in labs for more than a century, but the technique did not translate well to photographing shock structures outside the lab. But now NASA’s Armstrong Research Center and Ames Research Center have developed a method that allows them to capture highly-detailed images of the shock waves around airplanes while they are flying. This is incredible stuff. Be sure to check out the high-resolution versions on this page, along with more description of the coordination necessary to pull off the photos.

The light and dark lines you see emanating from the airplane are places with strong density gradients. The dark lines are mostly shock waves, with the strongest shock waves appearing black due to the large change in air density. Many of the light streaks are expansion fans, areas where the density and pressure drop as air speeds up.

The goal of this research is to better understand shock wave structures around supersonic planes in order to reduce the noise supersonic aircraft cause when flying overhead. As you can see in the photos, the shock waves at the nose and tail of the aircraft persist far away from the aircraft; these are what cause the twin sonic boom heard when the plane flies by. (Photo credit: NASA; via J. Hertzberg)