Venus is a world of extremes. A full rotation of the world takes 243 Earth days, but winds race around the planet at a speed that makes a Category 5 hurricane look sedate. Just what drives these winds has been an ongoing question for planetary scientists. A recent study suggests that tides are a major contributor to this superrotation.

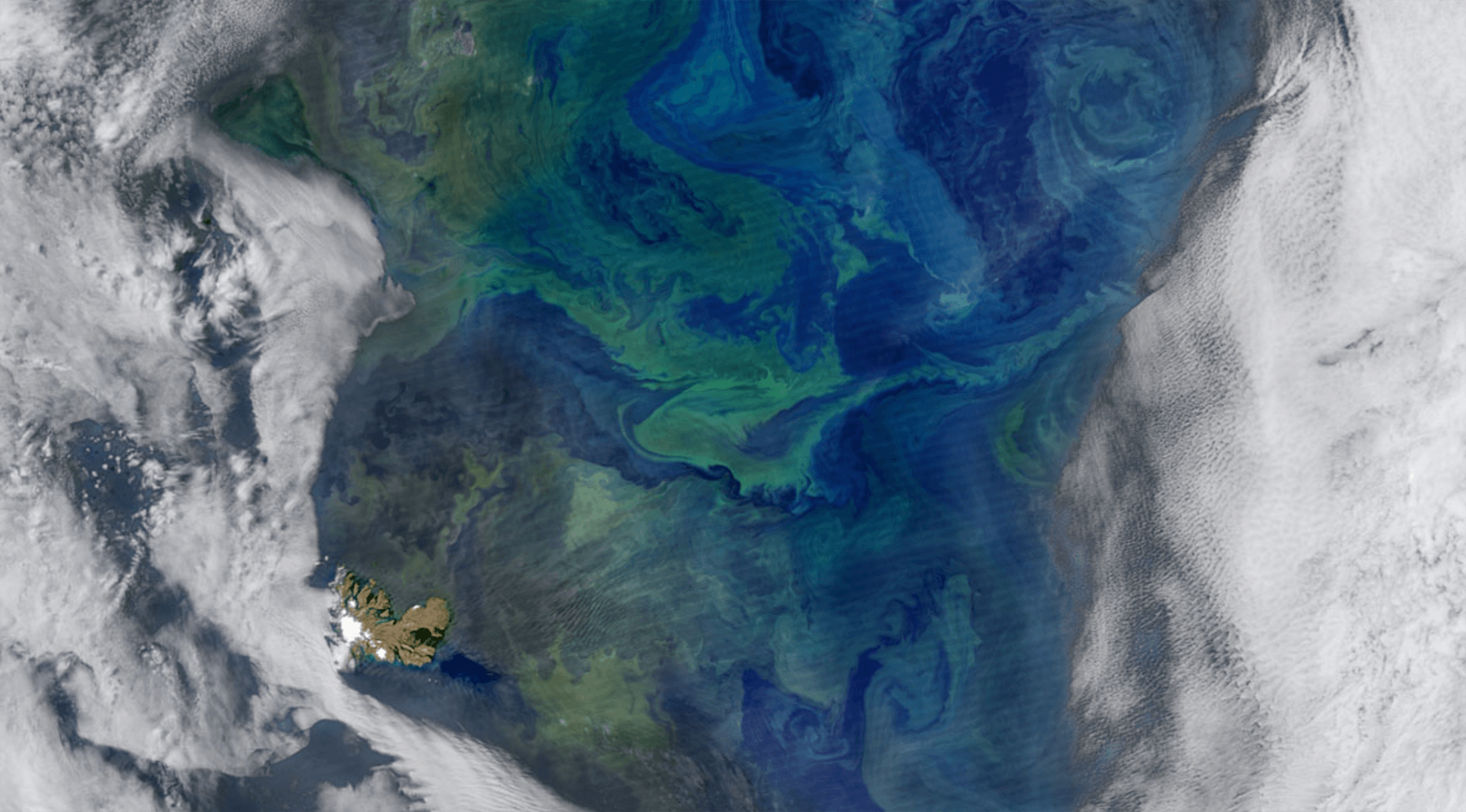

Unlike Earth’s tides, Venus’s are not gravitational in origin. Instead, Venusian tides are thermal, driven by heating in the sunward side of the atmosphere. This creates a diurnal tide, which cycles once per Venusian day and pumps momentum toward the tops of Venus’s clouds. The new analysis–rooted in both observations and numerical simulation–finds that diurnal tides are the primary driver behind the planet’s incredibly fast winds. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech; research credit: D. Lai et al.; via Eos)