Ice can be a terrible pest, freezing to surfaces like roads and airplane wings and causing all sorts of havoc. Some surfaces, though, can actually prompt a freezing drop to scrape itself off. There are a couple key effects in play here. The first is that the surface is nanotextured – in other words, it has extremely small structures on its surface. This makes it hydrophobic, or water-repellent. The second key ingredient is that the drop is cooling evaporatively; that means heat is escaping along the air-water interface instead of conducting through the solid surface. As a result, the freezing front forms at the interface and pushes inward. Water expands as it freezes, which tries to force the interior liquid out, toward the bottom of the drop. On a normal surface, this would force the contact line – where air, water, and surface meet – to push outward. But the nanotexture of the hydrophobic surface pins that line in place. So the expanding ice pushes the frozen drop upward, scraping it off the surface! (Video and image credit: G. Graeber et al., source)

Tag: freezing

“Dance Dance”

Artist Thomas Blanchard is no stranger to fluid dynamics. His previous short films focused on mixtures of oil and paint, but in “Dance Dance,” flowers are front and center. There are obvious splashes of color and clouds of diffusion toward the end of the video, but fluid dynamics are there throughout. The oozing, inexorable march of ice crystallizing over petals and leaves has a fluidity that’s heightened by timelapse. It’s a reminder that this phase change is unsteady and full of shifts too subtle to notice in real-time. In the second act, we see flowers blossoming in timelapse, bursting open dramatically before settling in with a subtle shift of their stamens. Motions like these are driven by the flow of fluids inside the plant. By shifting small concentrations of chemicals, plants drive the water in their cells via osmosis. This pumps up cells that cause the petals to spread and unfurl. (Video and image credit: T. Blanchard; via Colossal)

Skiing, Avalanches, and Freezing Bubbles

To wrap up our look at Olympic physics, we bring you a wintry mix of interviews with researchers, courtesy of JFM and FYFD. Learn about the research that helped French biathlete Martin Fourcade leave PyeongChang with 3 gold medals, the physics of avalanches, and how bubbles freeze.

If you missed any of our previous Olympic coverage, you can find our previous entries on the themed series page, and for more great interviews with fluids researchers, check out our previous collab video. (Video credit: T. Crawford and N. Sharp; image credits: GettyImages, T. Crawford and N. Sharp)

PyeongChang 2018: Ice-Making

When it comes to winter sports, not all ice is created equal. Every discipline has its own standards for the ideal temperature and density of ice, which makes venue construction and maintenance a special challenge. Figure skating, for example, requires softer ice to cushion athletes’ landings, whereas short-track speed skating values dense, smooth ice for racing. The Gangneung Ice Arena hosts both and can transition between them in under 3 hours. Gangneung Oval hosts long-track speed skating and makes its ice layer by layer, spraying hot, purified water onto the rink. This builds up a particularly dense and therefore smooth ice.

The toughest sport in terms of ice conditions is curling, which requires a finely pebbled ice surface for the stones to slide on. Forming those tiny crystals on the ice sheet can only be done at precise temperature and humidity conditions. This is a particular challenge for Gangneung Curling Center due to its coastal location. To keep the temperature and humidity under control at full crowd capacity, officials even went so far as to replace all the lighting at the facility with LEDs! (Image credit: Pyeongchang 2018, 1, 2, 3)

PyeongChang 2018: Snow-Making

These days artificial snow-making is a standard practice for ski resorts, allowing them to jump-start the early part of the season. Snow guns continuously spray a mixture of cold water and particulates 5 or more meters in the air to generate artificial snow. The tiny droplet size helps the water freeze faster and the particles provide nucleation sites for snow crystals to form. As with natural snow, the shape and consistency of the snow depends on humidity and temperature conditions. Pyeongchang is generally cold and dry, so even the artificial snow there tends to be similar to snow in the Colorado Rockies. Recreational skiers tend to look down on artificial snow, but Olympic course designers actually prefer it. With artificial snow, they can control every aspect of an alpine course. For them, natural snowfall is a disruption that puts their design at risk. (Video credit: Reactions/American Chemical Society)

Ice Bridges

During winter, Canada’s Arctic Archipelago, home of the Northwest Passage, generally fills with sea ice. These ice bridges form in the long and narrow straits between islands. A new paper models ice bridge formation and break-up, showing that ice bridges can only form when ice floating in the strait is sufficiently thick and compact. To form a bridge, wind must first push the ice together and then frictional forces between individual pieces of ice must be large enough to resist wind or water driving them apart. As temperatures drop, the individual ice chunks can then freeze together into solid sheets until summer returns.

The existence of a critical thickness and density of the ice field for ice bridge formation has important implications for climate change. As Arctic temperatures warm for longer periods, these waters may no longer generate ice of sufficient thickness and quantity for ice bridges to form. Since ice bridges serve as important oases for marine mammals and sea birds and help isolate Arctic sea ice from warmer waters, their loss will have a profound impact on both Arctic ecology and global climate. (Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory; research credit: B. Rallabandi et al.; via Physics Buzz)

Icy Spikes

Water is one of those strange materials that expands when it freezes, which raises an interesting question: what happens to a water drop that freezes from the outside in? A freezing water droplet quickly forms an ice shell (top image) that expands inward, squeezing the water inside. As the pressure rises, the droplet develops a spicule – a lance-like projection that helps relieve some of the pressure.

Eventually the spicule stops growing and pressure rises inside the freezing drop. Cracks split the shell, and, as they pull open, the cracks cause a sudden drop in pressure for the water inside (middle image). If the droplet is large enough, the pressure drop is enough for cavitation bubbles to form. You can see them in the middle image just as the cracks appear.

After an extended cycle of cracking and healing, the elastic energy released from a crack can finally overcome surface energy’s ability to hold the drop together and it will explode spectacularly (bottom image). This only happens for drops larger than a millimeter, though. Smaller drops – like those found in clouds – won’t explode thanks to the added effects of surface tension. (Image credit: S. Wildeman et al., source)

ETA: A previous version of this post erroneously said this was freezing from the “inside out” instead of “outside in”.

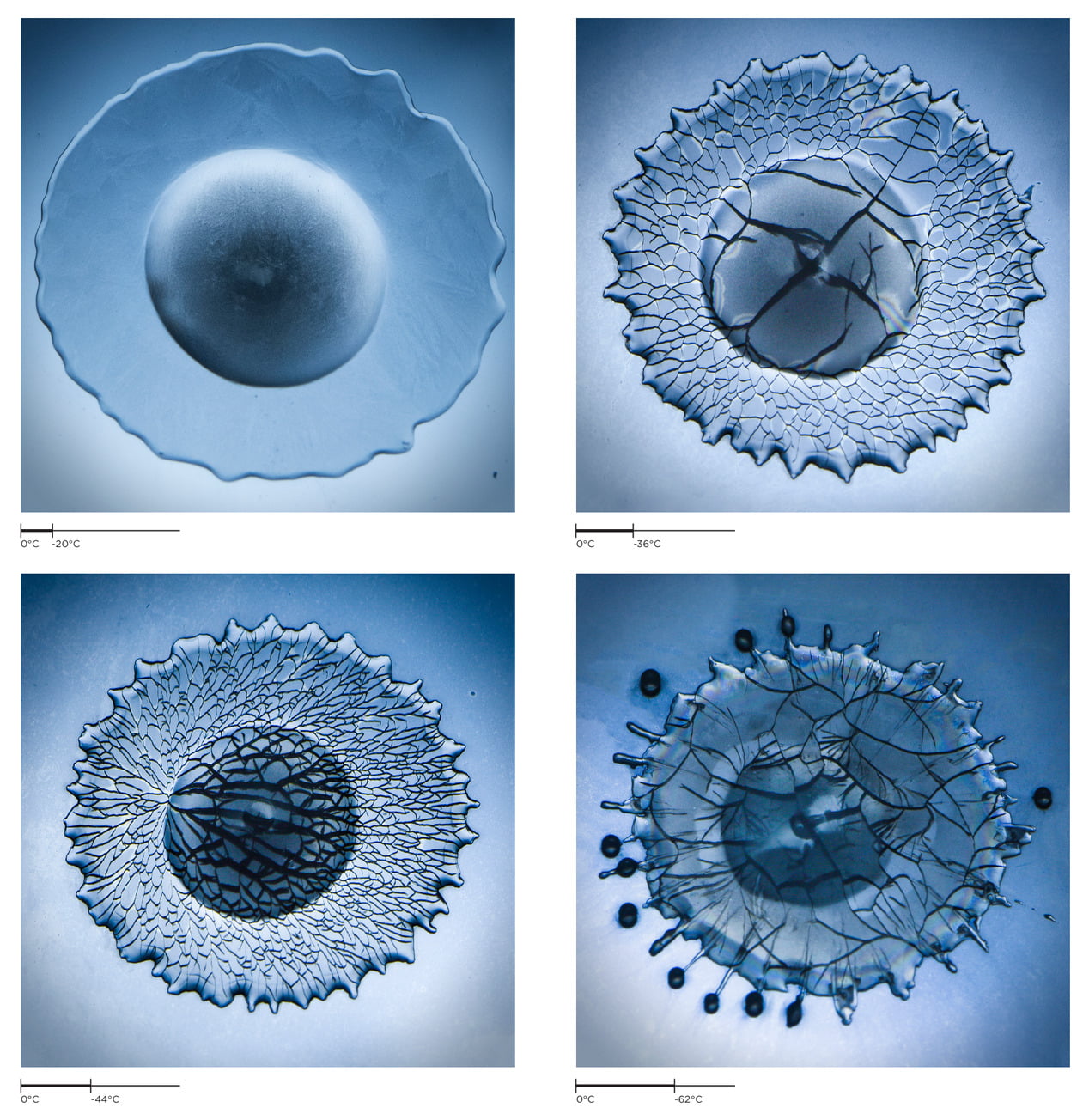

Freezing Impact

When a water droplet hits a frozen surface, what happens depends significantly on the temperature of the substrate. At relatively high temperatures (-20 degrees C), the droplet freezes without any cracking (upper left). As the surface gets colder, drops begin to crack. At first the cracks are relatively large and unstructured (upper right), but at lower temperatures, they grow in a network of smaller cracks with more distinctive structure (lower left). Cold temperatures can also affect the contact line where water, air, and substrate meet. This can cause droplets to splash even as they’re freezing (lower right). (Image credit: V. Thievenaz et al.; see also E. Ghabache et al.)

Freezing Bubbles

Soap bubbles are wonderfully ephemeral, their surfaces constantly in motion as air currents, surface tension variations, and temperature differences make them dance. In this video, though, photographer Paweł Załuska focuses on freezing soap bubbles. Watching the growth of ice crystals across the bubbles’ thin surface is mesmerizing. Snowflake-like crystals can nucleate anywhere on the film and, as in the sequence at 0:48, those crystals can float around on the bubble’s surface like snowflakes drifting on a breeze until enough of the film solidifies to bring the bubble to a halt and, then, a collapse. (Video credit: P. Załuska/ZALUSKart; via Gizmodo)

Washington Ice Disk

Winter weather in northern latitudes sometimes brings with it unusual phenomena like this ice disk spinning in the Middle Fork Snoqualmie River in Washington state. Photographer Kaylyn Messer ventured out to capture photos and videos of the event over the weekend. There are a couple theories as to how such disks form, but swirling river eddies are a key ingredient. One theory posits that chunks of ice forming on the river get caught up by the spinning eddy and slowly freeze together to form the disk. Another theory proposes that the disks occur when an existing chunk of ice breaks away, gets caught in the spinning eddy and slowly has its edges ground down into a circle. Personally, I lean toward the former explanation, though there is likely grinding at the edges either way. See more about this ice circle over at Messer’s blog. (Image credit: K. Messer; GIF by @itscolossal; via Colossal)