Vibration is one method for breaking a drop into smaller droplets, a process known as atomization. Here, researchers simulate this break-up process for a drop in microgravity. Waves crisscrossing the surface create localized craters and jets, making the drop resemble the Greek mythological figure of Medusa. With enough vibrational amplitude, the jets stretch to point of breaking, releasing daughter droplets. (Image and research credit: D. Panda et al.)

Tag: computational fluid dynamics

Fish Fins Work Together

Researchers studying how fish swim have long focused on their tail fins and the flows created there. But a fish’s other fins have important effects, too, as seen in this recent study. Researchers built a CFD simulation based on observations of a swimming rainbow trout, focusing on the flow from its back and tail fins. They found that the vortex created by the back fin stabilizes and strengthens the one generated by the tail. It also played a role in reducing drag on the fish by maintaining the pressure difference across the body. When they tried changing the size and geometry of the fins, the fish’s efficiency suffered, indicating that evolution has already optimized the trout’s fins for swimming efficiency. (Image credits: top – J. Sailer, simulation – J. Guo et al.; research credit: J. Guo et al.; via APS Physics)

Visualization of flow around a digitized rainbow trout.

Predicting Contamination in Urban Environs

The canyons of a city’s streets form a complex flow environment. To better understand the risks of a spreading contaminant, researchers simulated a release in lower Manhattan’s urban jungle. The released particles spread due to the dominant wind pattern of the area. Initially, the particles follow the street pattern and stay at a low elevation. But updrafts on the downwind side of skyscrapers lift the particles higher, spreading them to lower concentrations at more elevations.

Public officials study simulations like these to understand what response is needed to protect people in the event of an accidental or intentional release of harmful materials. (Image and video credit: W. Oaks and A. Khosronejad)

A Bubble’s Path

Centuries ago, Leonardo da Vinci noticed something peculiar about bubbles rising through water. Small bubbles followed a straight path, but slightly larger ones swung back and forth or corkscrewed upward. The mechanism behind this behavior has been a matter of debate ever since, but the authors of a recent study believe they’ve nailed down the answer.

The forces determining a bubble’s path are remarkably complex, which is why it’s taken so long to figure this out. Viscosity acts as a source of drag on the rising bubble, acting across a thin boundary region surrounding the bubble. That boundary isn’t constant, though; the bubble’s shape changes as the flow pushes on it, and the changing shape of the bubble pushes on the flow, in turn. Capturing those subtle interactions numerically and comparing them to careful experiments was necessary to unravel the mystery.

The team found that bubbles above a critical radius (0.926 millimeters) begin to tilt. That tilt causes a change in the bubble’s shape, which increases the flow along one side. This kicks off the wobbling motion, which carries on because of the continuing changes in the bubble’s shape and the flow around it. (Image credit: A. Grey; research credit: M. Herrada and J. Eggers; via Vice; submitted by @lediva)

Swimming Intermittently

Many fish do not swim continuously; instead, they use an intermittent motion, swimming in a sudden burst and then coasting. This intermittent swimming is tough to simulate, due to its unsteady nature, but a new study does so using some clever computational techniques.

Animation showing a fish swimming in a burst-and-coast pattern. Researchers suspected that the energy intensity of a fish’s burst could be balanced by the low-drag, low-effort phase of coasting. And, indeed, that’s consistent with the team’s results. But they found that the swimming method does require careful optimization; with the wrong cadence, the burst-and-coast technique can be incredibly energy intensive. In nature, of course, fish have had millions of years to optimize their technique, but the results serve as a warning to those building fish-based robots. Those biorobots will need careful optimization to benefit from this swimming style. (Image credit: tetra – Adobe Stock Images, simulation – G. Li et al.; research credit: G. Li et al.; via APS Physics; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

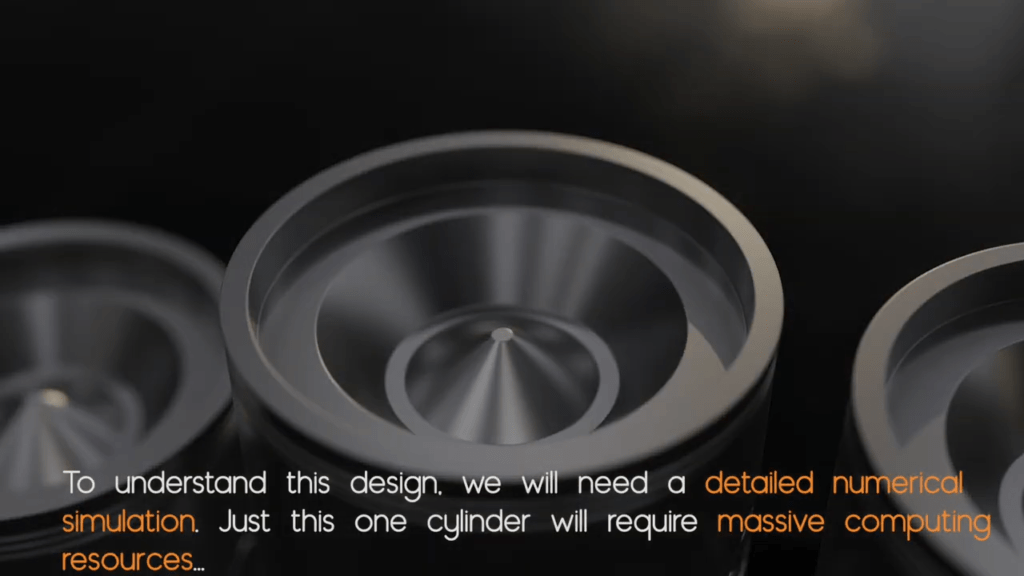

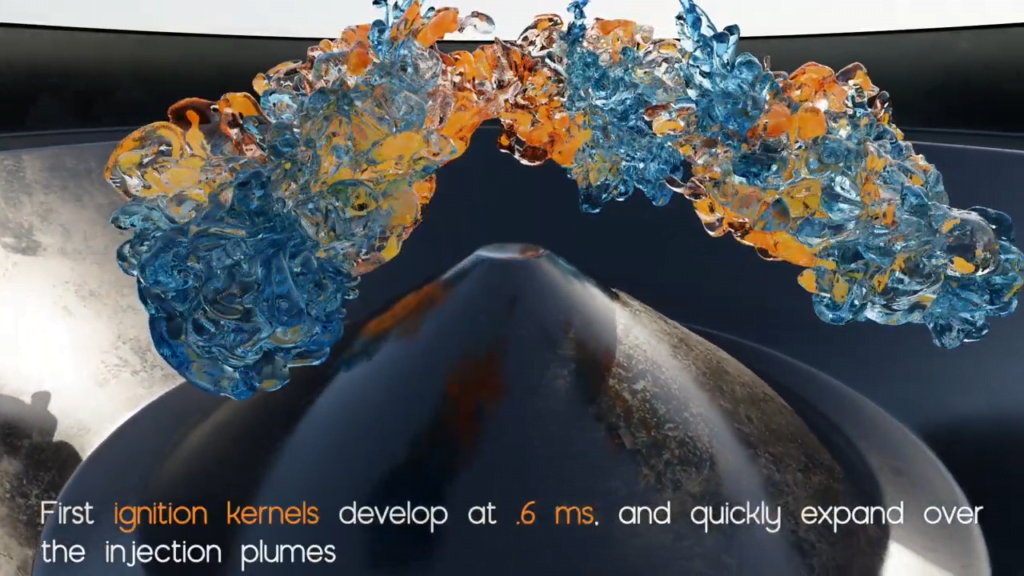

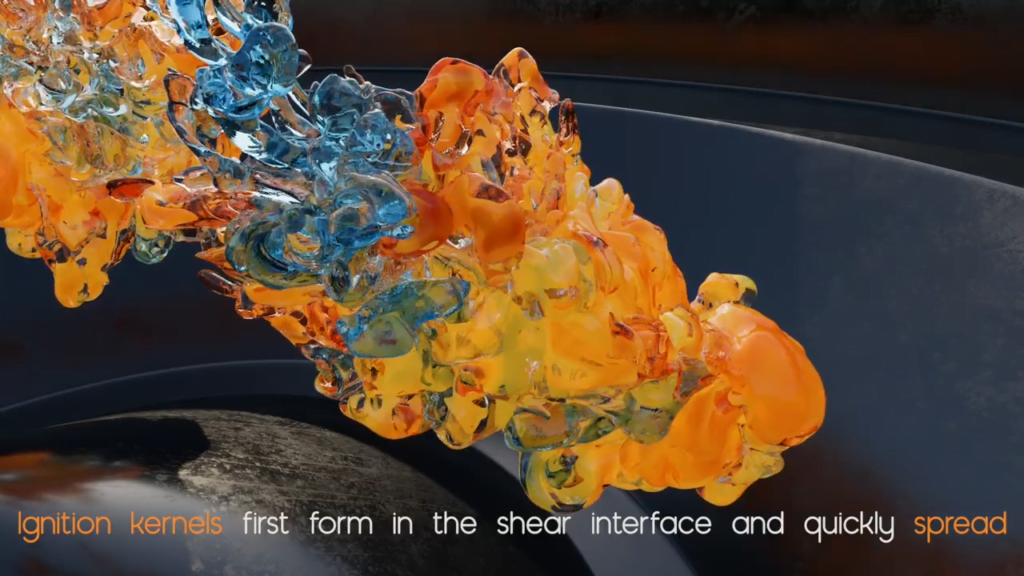

Exascale Simulations

Capturing what goes on inside a combustion engine is incredibly difficult. It’s a problem that depends on turbulent flow, chemistry, heat transfer, and more. To represent all of those aspects in a numerical simulation requires enormous computational resources. It’s not simply the realm of a supercomputer; it requires some of the fastest supercomputers in existence.

Exascale computing, like that used for the simulations in this video, is defined as at least 10^18 (floating-point) operations per second. For comparison, my PC has a recent, high-end graphics card, and it’s about a million times slower than that. These are absolutely gigantic simulations. (Image and video credit: N. Wimer et al.)

Why Moths Are Slow Fliers

Hawkmoths and other insects are slow fliers compared to birds, even ones that can hover. To understand why these insects top out at 5 m/s, researchers simulated their flight from hovering to forward flight at 4 m/s. They analyzed real hawkmoths flying in wind tunnels to build their simulated insects, then studied their digital moths with computational fluid dynamics.

During hovering flight, they found that hawkmoths generate equal amounts of lift with their upstroke and downstroke. As the moth transitions into forward flight, though, its wing orientation shifts to reduce drag, and the upstroke stops being so helpful. Instead, the upstroke generates a downward lift that the downstroke has to counter in addition to the insect’s weight. At higher forward speeds, this trend gets even worse.

The final verdict? Hawkmoths don’t have the flexibility to twist their wings on the upstroke the way birds do to avoid that large downward lift. Since they can’t mitigate that negative lift, the insects have a slower top speed overall. (Image and research credit: S. Lionetti et al.; via APS Physics; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

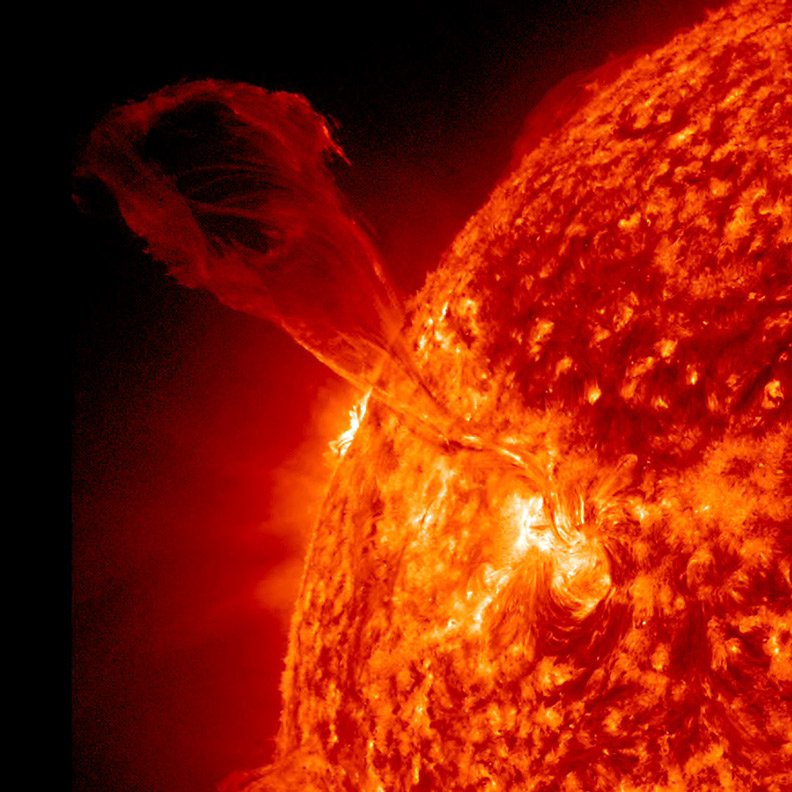

Escaping the Sun

One enduring mystery of the solar wind — a stream of high-energy particles expelled from the sun — is how the particles get accelerated in the first place. The sun frequently belches out spurts of plasma, but without further momentum, that material simply falls back to the sun’s surface under the star’s gravity. Mechanisms like shock waves can further accelerate particles that are already moving quickly, but they cannot explain how the particles get going in the first place.

A recent study used supercomputers to tackle this challenging problem in turbulent plasma physics. Each simulation tracked nearly 200 billion particles, requiring tens of thousands of processors. The results showed that turbulence itself provides the necessary initial acceleration and serves as the first step to getting particles moving fast enough to escape the sun. (Image credit: NASA SDO; research credit: L. Comisso and L. Sironi; via Physics World)

Inside a Champagne Pop

When the cork pops on a bottle of champagne, the physics is akin to that of a missile launch in more ways than one. In this study, researchers used computational fluid dynamics to closely examine the gases that escape behind the cork. They identified three phases to the flow. In the first, the exhaust gases form a crown-shaped expansion region, complete with shock diamonds. Once the cork has moved far enough downstream, the axial flow accelerates to supersonic speeds and a bow shock forms behind the cork. Finally, the pressure in the bottle drops low enough that supersonic conditions cannot be maintained and the flow becomes subsonic. (Image credit: top – Kindel Media, simulation – A. Benidar et al.; research credit: A. Benidar et al.; via Ars Technica; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

A numerical simulation showing the ejection of a champagne cork from a bottle. The colors indicate the speed of gases escaping from the bottle.

Asperitas Formation

In 2017, the World Meteorological Organization named a new cloud type: the wave-like asperitas cloud. How these rare and distinctive clouds form is still a matter of debate, but this new study suggests that they need conditions similar to those that produce mammatus clouds, plus some added shear.

Using direct numerical simulations, the authors studied a moisture-filled cloud layer sitting above drier ambient air. Without shear, large droplets in this cloud layer slowly settle downward. As the droplets evaporate, they cool the area just below the cloud, changing the density and creating a Rayleigh-Taylor-like instability. This is one proposed mechanism for mammatus clouds, which have bulbous shapes that sink down from the cloud.

When they added shear to the simulation, the authors found that instead of mammatus clouds, they observed asperitas ones. But the amount of shear had to be just right. Too little shear produced mammatus clouds; too much and the shear smeared out the sinking lobes before they could form asperitas waves. (Image credit: A. Beatson; research credit: S. Ravichandran and R. Govindarajan)