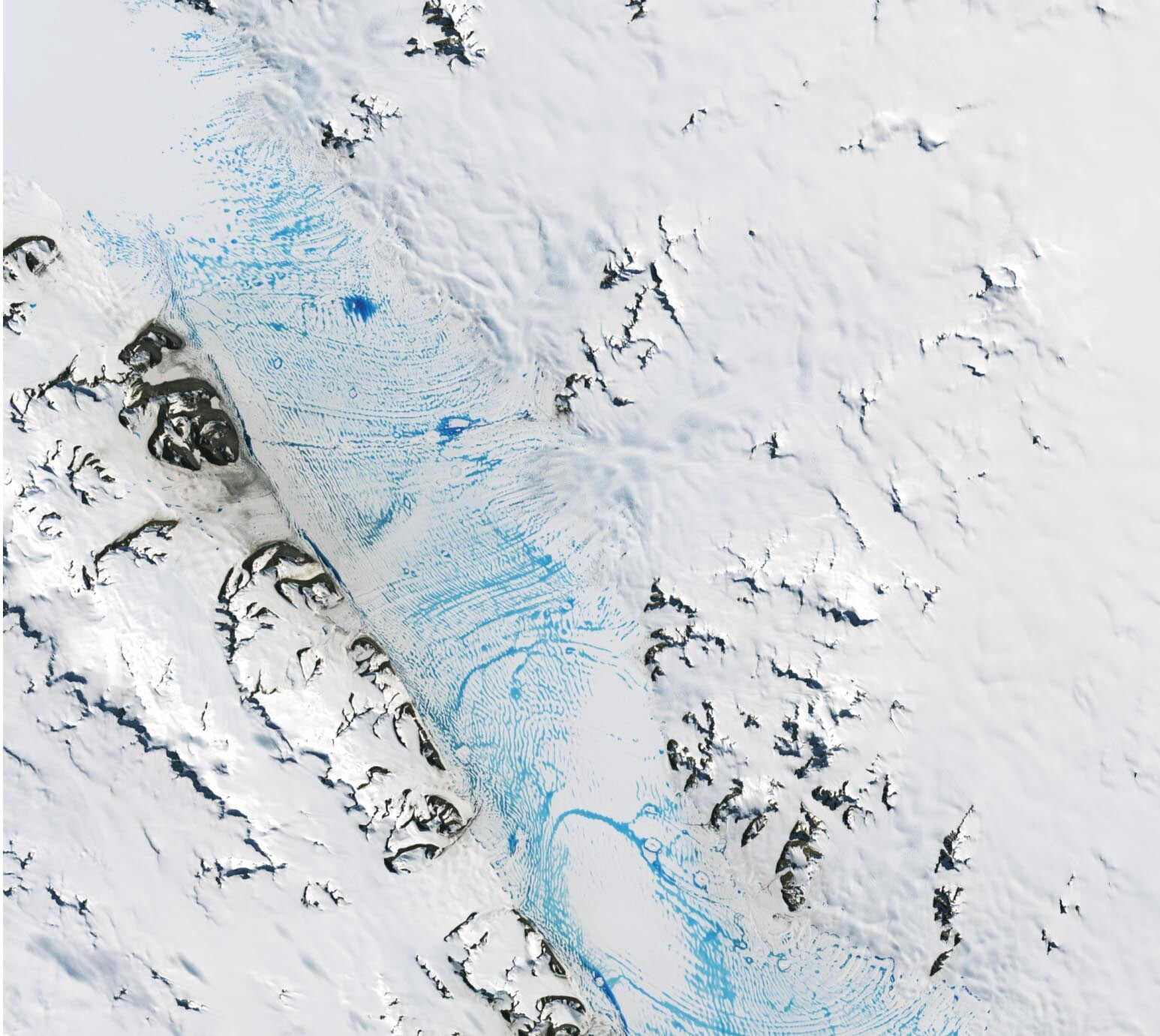

Cerulean blue meltwater glints in this satellite image of the George VI Ice Shelf. Wedged between the Antarctic Peninsula on the right and Alexander Island on the left, the ice shelf itself floats on the ocean. When ice shelves collapse, they do not directly raise sea levels since their weight has already displaced water; but a collapsed ice shelf lets glaciers flow and break up faster, thereby raising water levels.

In past ice shelf collapses, scientists have noted major buildup and sudden drainage of surface lakes like the ones seen here. Meltwater penetrating through snow and ice can destabilize the shelf and hasten collapse, but the exact mechanisms are hard to track. This Physics Today article summarizes our understanding of the process and some of the methods scientists use to study it. (Image credit: L. Dauphin/NASA Earth Observatory; see also Physics Today)