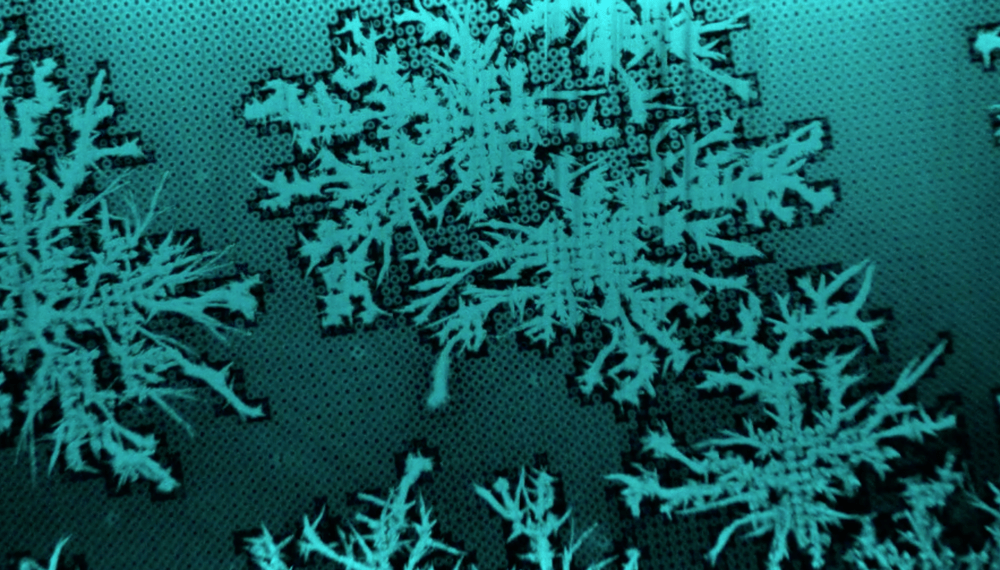

Ice — as we typically encounter it — is extremely brittle and easily broken. That’s due to defects in the ice, places where atoms have settled into a spot that does not match the perfect crystalline alignment. Because tiny defect-free threads of ice made by researchers turn out to be wildly flexible!

To make these perfect ice strands, each of which is a tiny fraction of the thickness of a human hair, researchers applied an electric voltage to a needle in a water-vapor-filled chamber. The technique condensed ice microfibers with perfect crystal structures in a matter of seconds. When bent, the microfibers actually shift from one crystalline arrangement to another in order to carry stress, and once the force is removed, the thread reverts back to its initial straight form. (Image and research credit: P. Xu et al.; via Science News; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)