At times altocumulus cloud cover is pierced by circular or elongated holes, filled only with the wispiest of virga. These odd holes are known by many names: cavum, fallstreak holes, and hole punch clouds. Long-running debates about these clouds’ origins were put to rest some 14 years ago, after scientists showed they were triggered by airplanes passing through layers of supercooled droplets.

When supercooled, water droplets hang in the air without freezing, even though they are colder than the freezing point. This typically happens when the water is too pure to provide the specks of dust or biomass needed to form the nucleus of an ice crystal. But when an airplane passes through, the air accelerated over its wings gets even colder, dropping the temperature another 20 degrees Celsius. That is cold enough that, even without a nucleus, water drops will freeze. More and more ice crystals will form, until they grow heavy enough to fall, leaving behind a clear hole or wisps of falling precipitation.

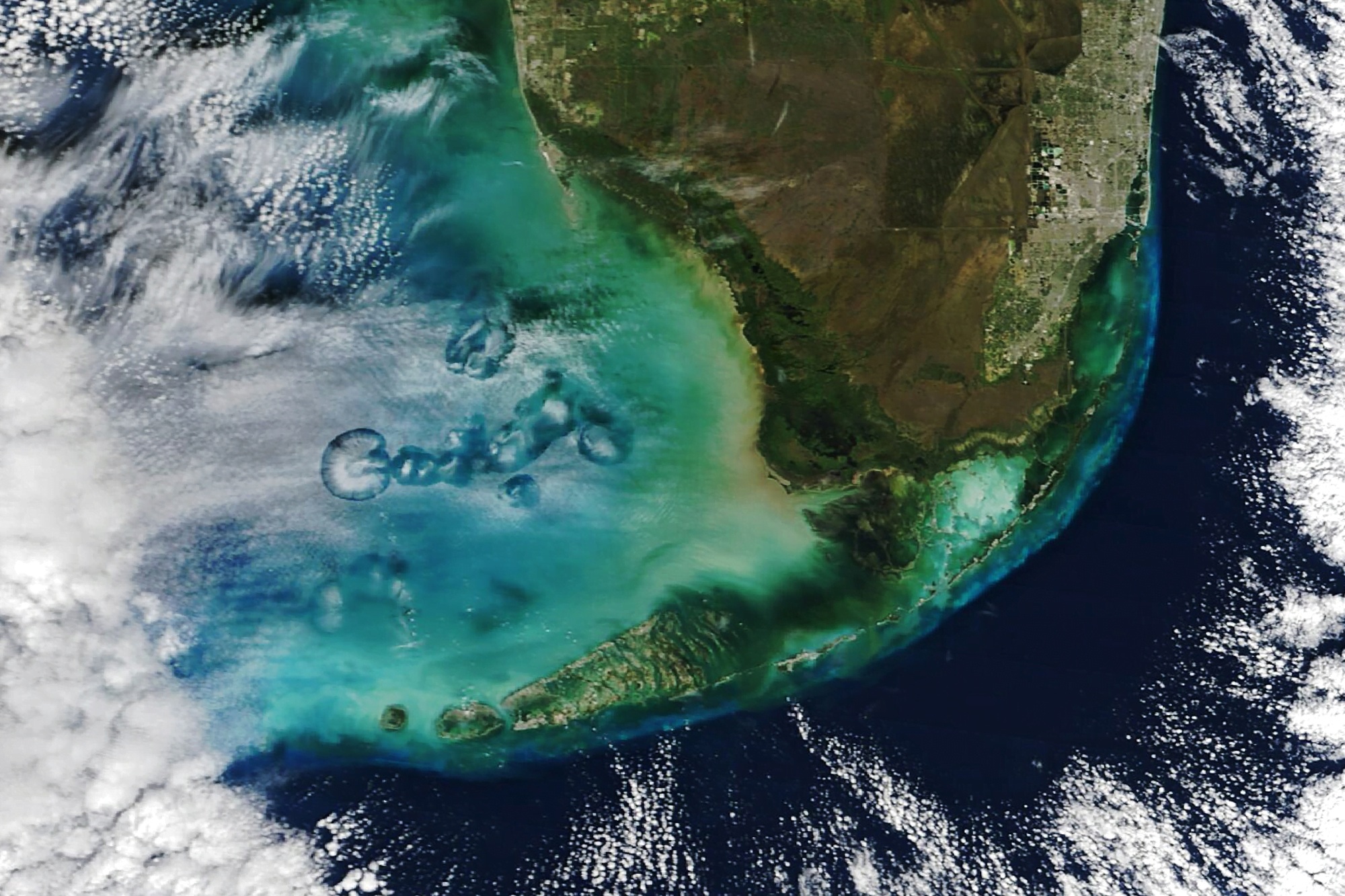

In the satellite image above, flights moving in and out of Miami International Airport have left a variety of holes in the cloud cover each of them large enough to see from space! (Image credit: M. Garrison; research credit: A. Heymsfield et al. 2010 and A. Heymsfield et al. 2011; via NASA Earth Observatory)