Welcome to another year and another look back at FYFD’s most popular posts. (You can find previous editions, too, for 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, and 2014. Whew, that’s a lot!) Here are some of 2024’s most popular topics:

- The Taum Sauk Dam Failure and Its Legacy

- Stretching Ant Rafts

- Gigapixel Supernova

- Feynman’s Sprinkler Solved

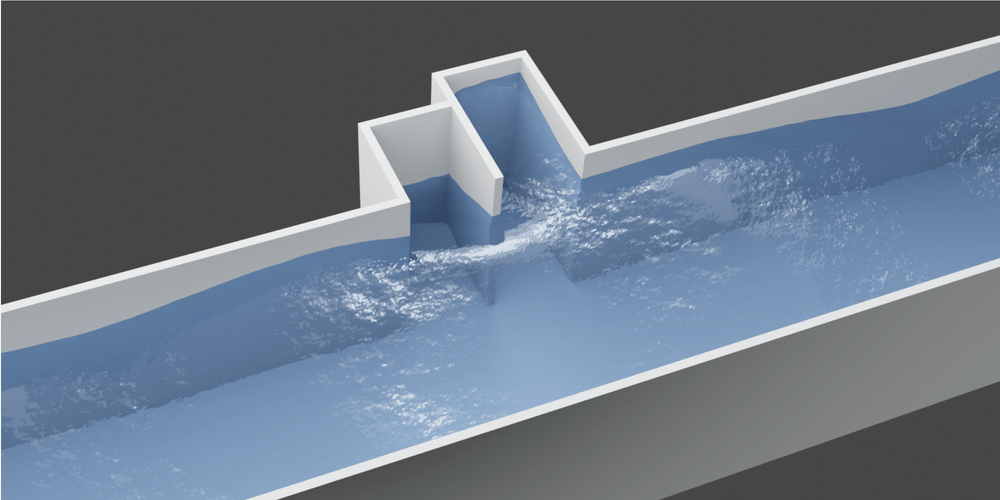

- Calming the Waves

- “Dew Point” Deposits Droplets

- Drying Unaffected by Humidity

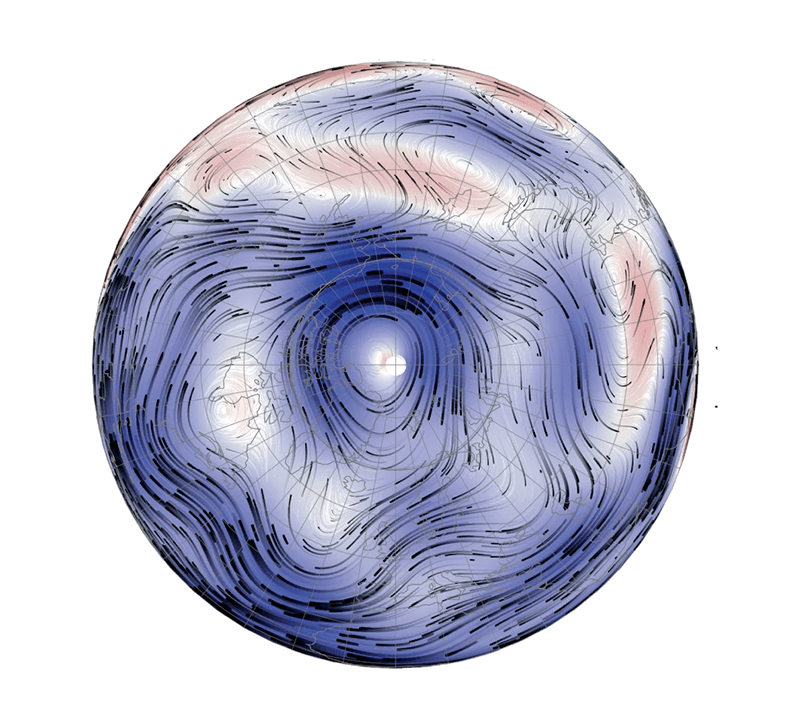

- Trapped in a Taylor Column

- Exciting a Flame in a Trough

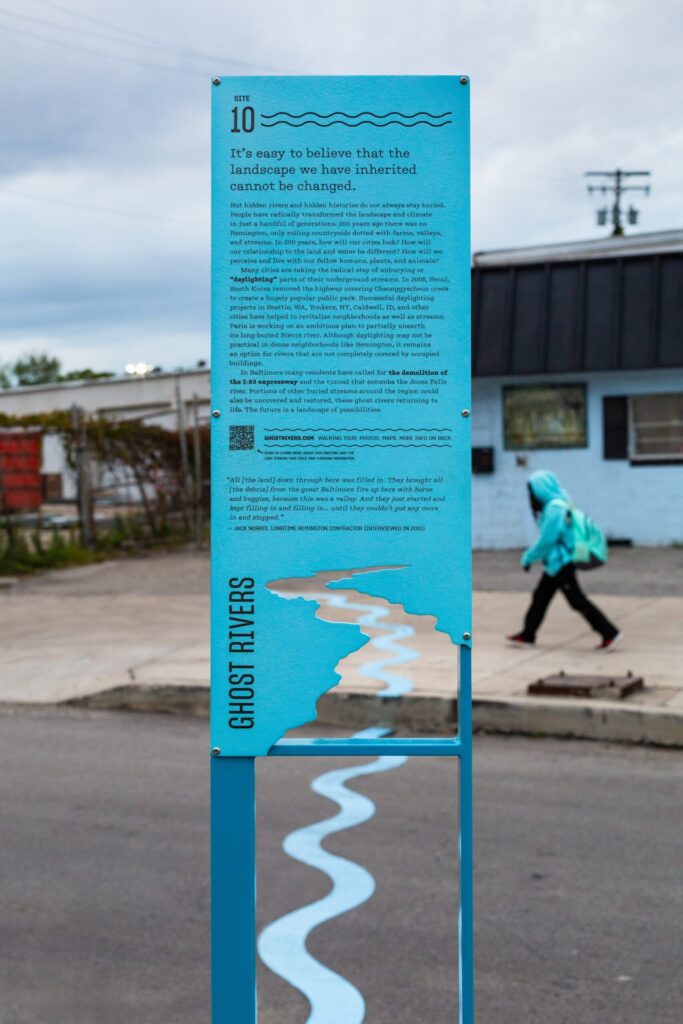

- Remembering Rivers Past

- A Comet’s Tail

- Light Pillars

- Liquid Metal Printing

- The Miscible Faraday Instability

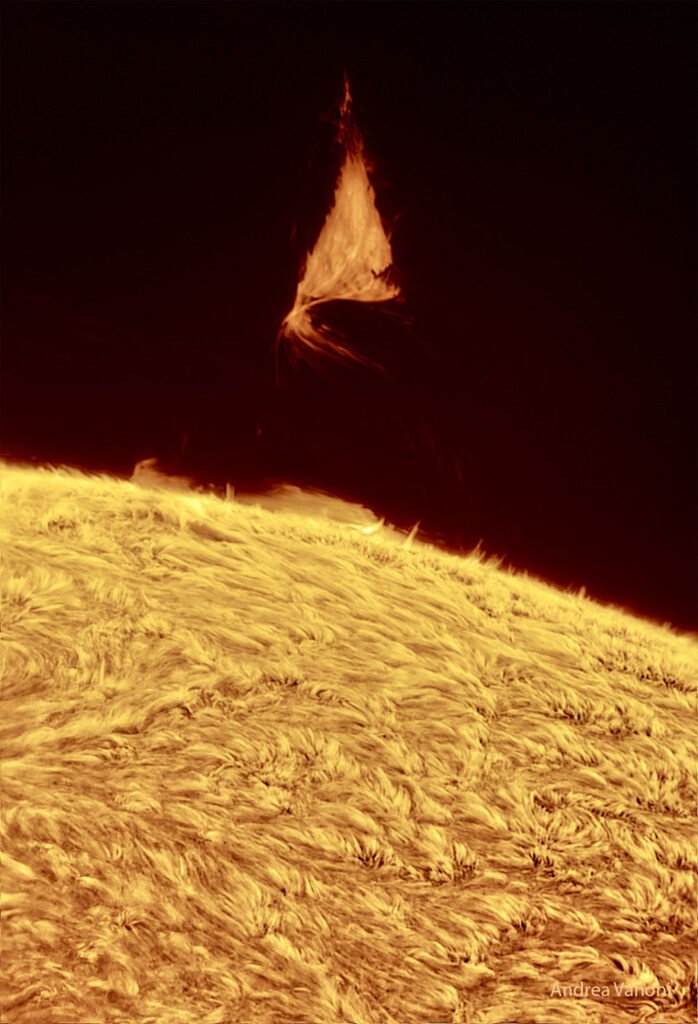

- A Triangular Prominence

This year’s topics are a good mix: fundamental research, civil engineering applications, geophysics, astrophysics, art, and one good old-fashioned brain teaser. Interested in what 2025 will hold? There are lots of ways to follow along so that you don’t miss a post.

And if you enjoy FYFD, please remember that it’s a reader-supported website. I don’t run ads, and it’s been years since my last sponsored post. You can help support the site by becoming a patron, buying some merch, or simply by sharing on social media. And if you find yourself struggling to remember to check the website, remember you can get FYFD in your inbox every two weeks with our newsletter. Happy New Year!

(Image credits: dam – Practical Engineering, ants – C. Chen et al., supernova – NOIRLab, sprinkler – K. Wang et al., wave tank – L-P. Euvé et al., “Dew Point” – L. Clark, paint – M. Huisman et al., iceberg – D. Fox, flame trough – S. Mould, sign – B. Willen, comet – S. Li, light pillars – N. Liao, chair – MIT News, Faraday instability – G. Louis et al., prominence – A. Vanoni)