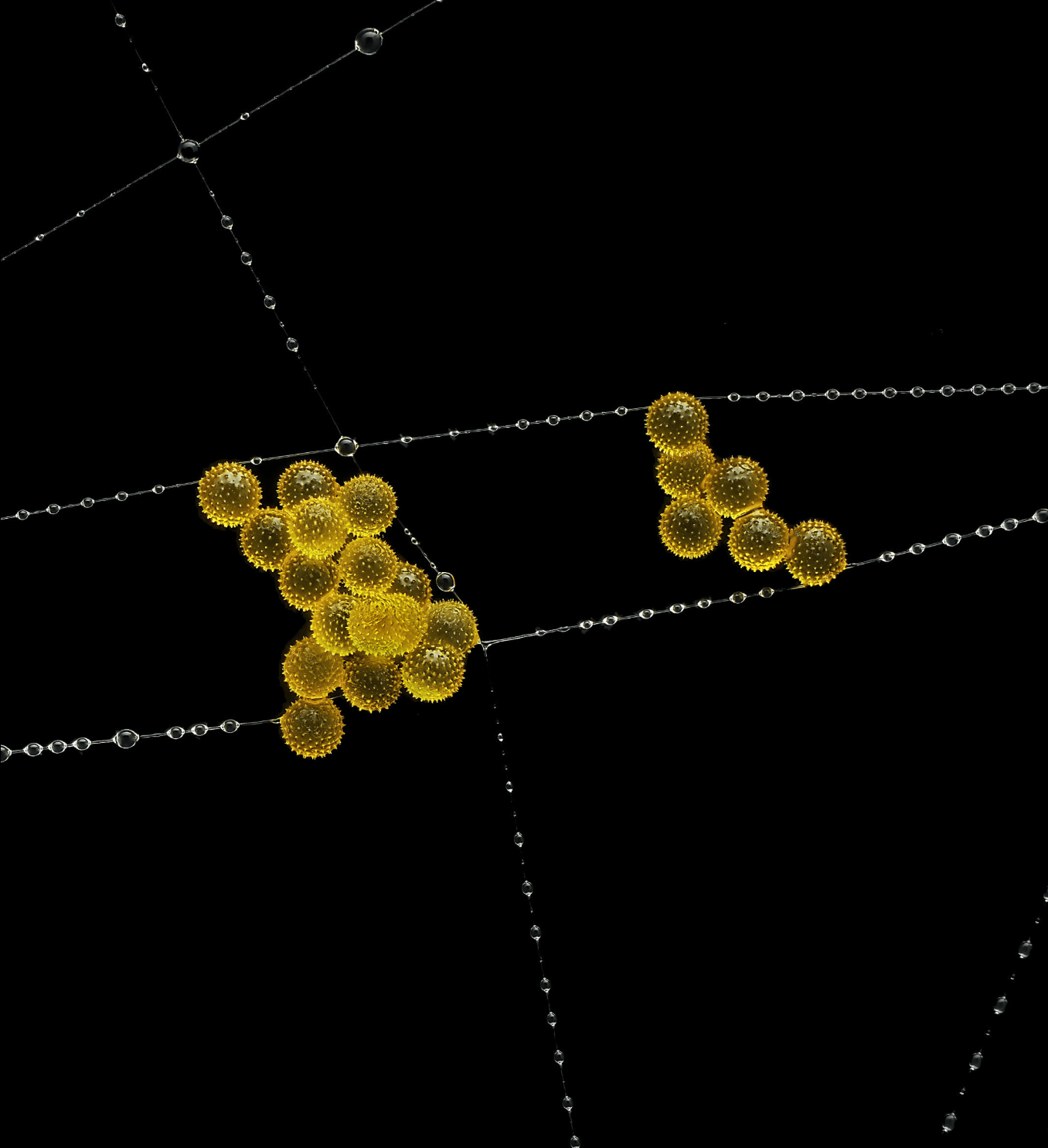

Grains of pollen are caught amid droplets on a spider’s web in this award-winning image by John-Oliver Dum. How droplets behave on fibers has been a popular topic in recent years with research on how droplets nestle into corners, how they slide on straight or twisted wires, the patterns formed by streams of falling drops, and what happens to a droplet on a plucked string. (Image credit: J. Dum; via Ars Technica)

Tag: surface tension

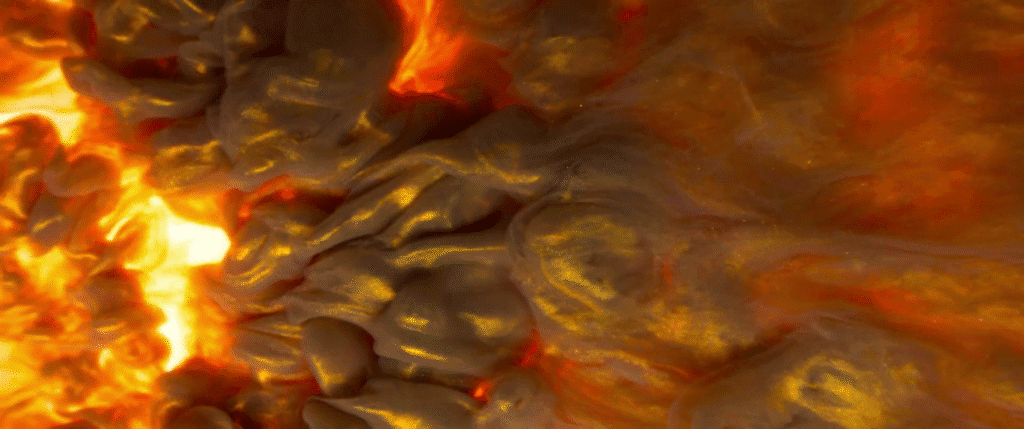

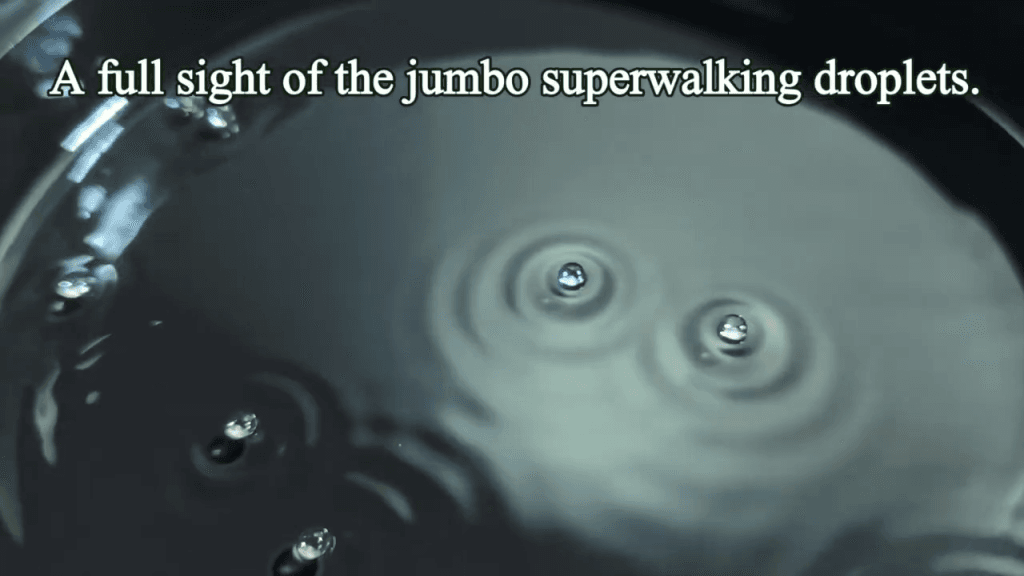

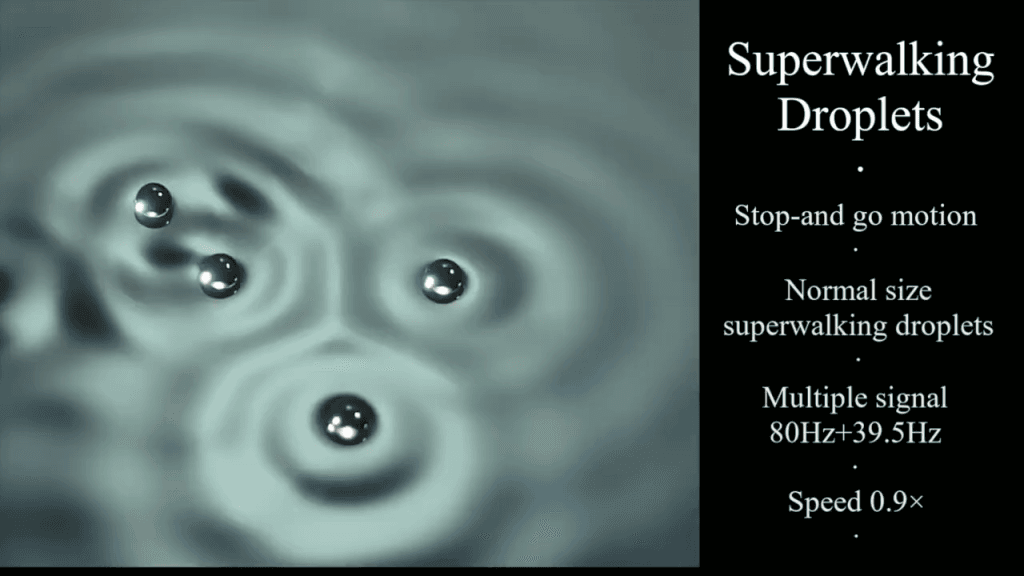

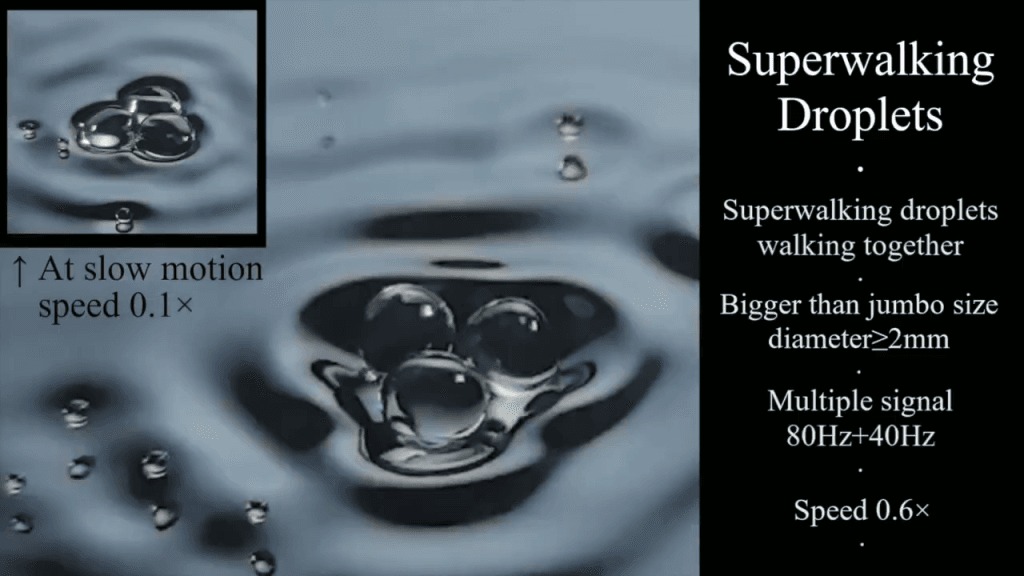

Superwalking Droplets

When placed on a vibrating oil bath, droplets have many wild behaviors, some of which mirror quantum mechanics. Even big droplets — bigger than 2 millimeters in diameter — can get in on the fun. This video shows several of these “jumbo superwalkers” in action, both singly and in groups. (Video and image credit: Y. Li and R. Valani; via GFM)

Marangoni Effect in Biology

For decades, biologists have focused on genetics as the key determiner for biological processes, but genetic signals alone do not explain every process. Instead, researchers are beginning to see an interplay between genetics and mechanics as key to what goes on in living bodies.

For example, scientists have long tried to unravel how an undifferentiated blob of cells develops a clear head-to-tail axis that then defines the growing organism. Researchers have found that, rather than being guided purely by genetic signals, this stage relies on mechanical forces–specifically, the Marangoni effect.

The image above shows a mouse gastruloid, a bundle of stem cells that mimic embryo growth. As they develop, cells flow up the sides of the gastruloid, with a returning downward flow down the center. This is the same flow that happens in a droplet with higher surface tension in one region; the Marangoni effect pulls fluid from the lower surface tension region to the higher one, with a returning flow that completes the recirculation circuit.

The same thing, it turns out, happens in the gastruloid. Genes in the cells trigger a higher concentration of proteins in one region of the bundle, creating a lower surface tension that causes tissue to flow away, helping define the head-to-tail axis. (Image credit: S. Tlili/CNRS; research credit: S. Gsell et al.; via Wired)

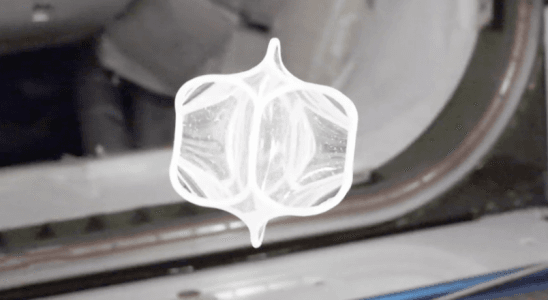

A Soft Cell in Microgravity

There are many shapes that can be tiled to fill space, but nearly all of them have sharp corners. Last year, mathematicians identified a new class of shapes, known as “soft cells,” that feature curved edges and faces but very few sharp corners. Like traditional polyhedrals, soft cells can tile to fill a space completely without overlapping or gapping.

Now the researchers, with some help from astronauts aboard the ISS, have brought one of their soft cells to life. Using an edge skeleton to guide the shape, astronaut Tibor Kapu filled the skeleton with water, which, in microgravity, formed a perfect soft cell, complete with faces curved by surface tension to their minimal area. See it in action below. (Image and video credit: HUNOR/NASA; research credit: G. Domokos et al.; via Oxford Mathematics)

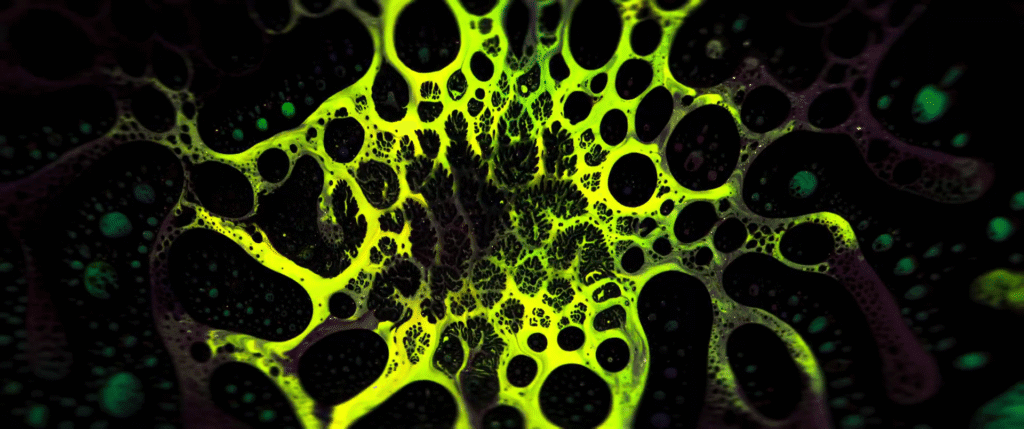

Marangoni Bursting With Surfactants

A few years ago, researchers described how an alcohol-water droplet atop an oil bath could pull itself apart through surface tension forces. Dubbed Marangoni bursting, this phenomena has shown up several times since. Here, researchers explore a twist on the behavior by adding surfactants to see how they affect the bursting phenomenon. (Video and image credit: K. Wu and H. Stone; via GFM)

The Balvenie

Photographer Ernie Button explores the stains left behind when various liquors evaporate. This one comes from a single malt scotch whisky by The Balvenie. The stain itself is made up of particles left behind when the alcohol and water in the whisky evaporate. The pattern itself depends on a careful interplay between surface tension, evaporation, pinning forces, and internal convection as the whisky puddle dries out. (Image credit: E. Button/CUPOTY; via Colossal)

Deep Breaths Renew Lung Surfactants + A Special Announcement

Taking a deep breath may actually help you breathe easier, according to a new study. When we inhale, air fills our alveoli–tiny balloon-like compartments within our lungs. To make alveoli easier to open, they’re coated in a surfactant chemical produced by our lungs. Just as soap’s surfactant molecules squeezing between water molecules lowers the interface’s surface tension, our lung surfactants gather at the interface and lower the surface tension, making alveoli easier to inflate.

But things are a little more complicated in our lungs than in our kitchen sink because of our constant cycle of breathing, which stretches and compresses our lungs’ surfaces and surfactant layers. Imagine a flat interface, lined with surfactant molecules; then stretch it. As the interface stretches, gaps open between the surfactant molecules and allowing molecules from the interior of the liquid to push their way to the newly stretched interface, changing the surface tension. If the interface gets compressed, some of the excess molecules will get pushed back into the liquid bulk.

In looking at how lung surfactants respond to these cycles of compression and stretching, the researchers found that the lung liquid develops a microstructure during cycles of shallow breathing that makes the surface tension higher, thus making lungs harder to fill. In contrast, a deep breath like a sigh replenished the saturated lipids at the interface, lowering surface tension and making lungs more compliant. So a deep sigh actually can help you breathe easier. (Image credit: F. Møller; research credit: M.. Novaes-Silva et al.; via Gizmodo)

P.S. — I’ve got a book (chapter)! Several years ago, I joined an amazing group of women to write two books (one for middle grades and one for older audiences) about our journeys as scientists. And they are out now! In fact, today we’re holding a “Book Bomb” where we aim for as many of us as possible to buy the book(s) on the same day. If you’d like to join (and get ahead on your gift shopping), here are (affiliate) links:

- Persevere, Survive, and Thrive (including my story of becoming a science communicator): Amazon, Bookshop.org

- For All the Curious Girls: Amazon, Bookshop.org

Wave Energy Through the Meniscus

Even small changes to a meniscus can change how much wave energy passes through it. A new study systemically tests how meniscus size and shape affects the transmission of incoming waves.

As seen above, the meniscus was formed on a suspended barrier. By changing the barrier size and wettability as well as the characteristics of incoming waves, researchers were able to map out how the meniscus affected waves that made it past the barrier.

In particular, they found that drawing the meniscus upward by raising the barrier would, at first, enhance wave transmission but then suppressed wave energy as the barrier moved higher. They attributed the change in behavior to an interplay between water column height and meniscus inclination. (Research and image credit: Z. Wang et al.; via Physics World)

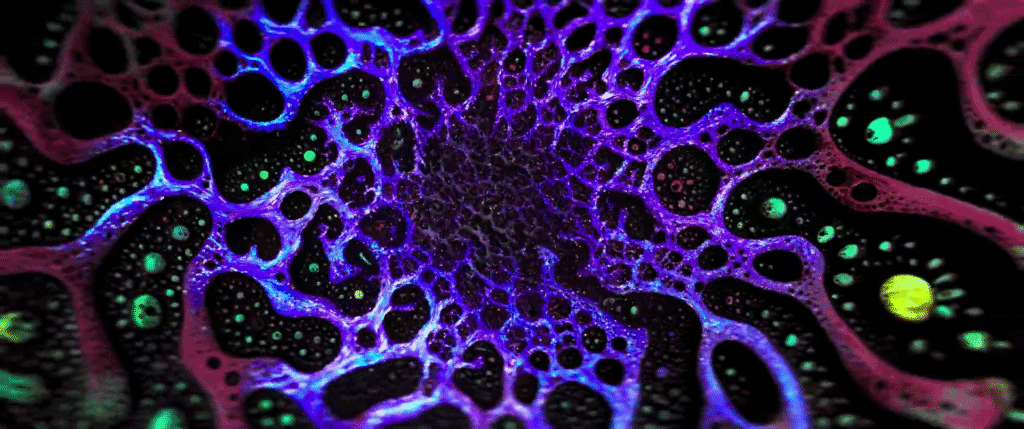

“Re:Birth”

In “Re:Birth,” videographer Vadim Sherbakov explores the fascinating patterns of ferrofluids, which suspend tiny ferrous particles in another liquid, often oil. When this magnetic liquid is mixed with ink or paint, its black lines take on a labyrinthine appearance. The result is rather psychedelic, especially with Sherbakov’s bold colors. (Video and image credit: V. Sherbakov)

Espresso in Slow-Mo

Espresso has some pretty cool physics. But it’s also just lovely to watch in slow motion. This video offers a look at the making of an espresso shot at 120 frames per second (though you can also enjoy a 1000 fps version here). Watching the film form, expand, and break up at the beginning and end of the video is my favorite, but watching how the occasional solid coffee grains make their way into and down the central jet is really interesting also. (Video and image credit: YouTube/skunkay; via Open Culture)

![Black and white image of a film pulled outward and breaking into droplets. Text reads, "The [0.05%] surfactant renders the ejected droplets prone to 'popping'." Black and white image of a film pulled outward and breaking into droplets. Text reads, "The [0.05%] surfactant renders the ejected droplets prone to 'popping'."](https://fyfluiddynamics.com/wp-content/uploads/surfburst2-1024x576.png)

![Black and white image of a film pulled outward and spreading in unevenly. Text reads, "When surfactant concentration is further increased [to 1%], drop spreading resumes." Black and white image of a film pulled outward and spreading in unevenly. Text reads, "When surfactant concentration is further increased [to 1%], drop spreading resumes."](https://fyfluiddynamics.com/wp-content/uploads/surfburst3-1024x576.png)