This image shows oil-flow visualization of a cylindrical roughness element on a flat plate in supersonic flow. The flow direction is from left to right. In this technique, a thin layer of high-viscosity oil is painted over the surface and dusted with green fluorescent powder. Once the supersonic tunnel is started, the model gets injected in the flow for a few seconds, then retracted. After the run, ultraviolet lighting illuminates the fluorescent powder, allowing researchers to see how air flowed over the surface. Image (a) shows the flat plate without roughness; there is relatively little variation in the oil distribution. Image (b) includes a 1-mm high, 4-mm wide cylinder. Note bow-shaped disruption upstream of the roughness and the lines of alternating light and dark areas that wrap around the roughness and stretch downstream. These lines form where oil has been moved from one region and concentrated in another, usually due to vortices in the roughness wake. Image © shows the same behavior amplified yet further by the 4-mm high, 4-mm wide cylinder that sticks up well beyond the edge of the boundary layer. Such images, combined with other methods of flow visualization, help scientists piece together the structures that form due to surface roughness and how these affect downstream flow on vehicles like the Orion capsule during atmospheric re-entry. (Photo credit: P. Danehy et al./NASA Langley #)

Tag: NASA

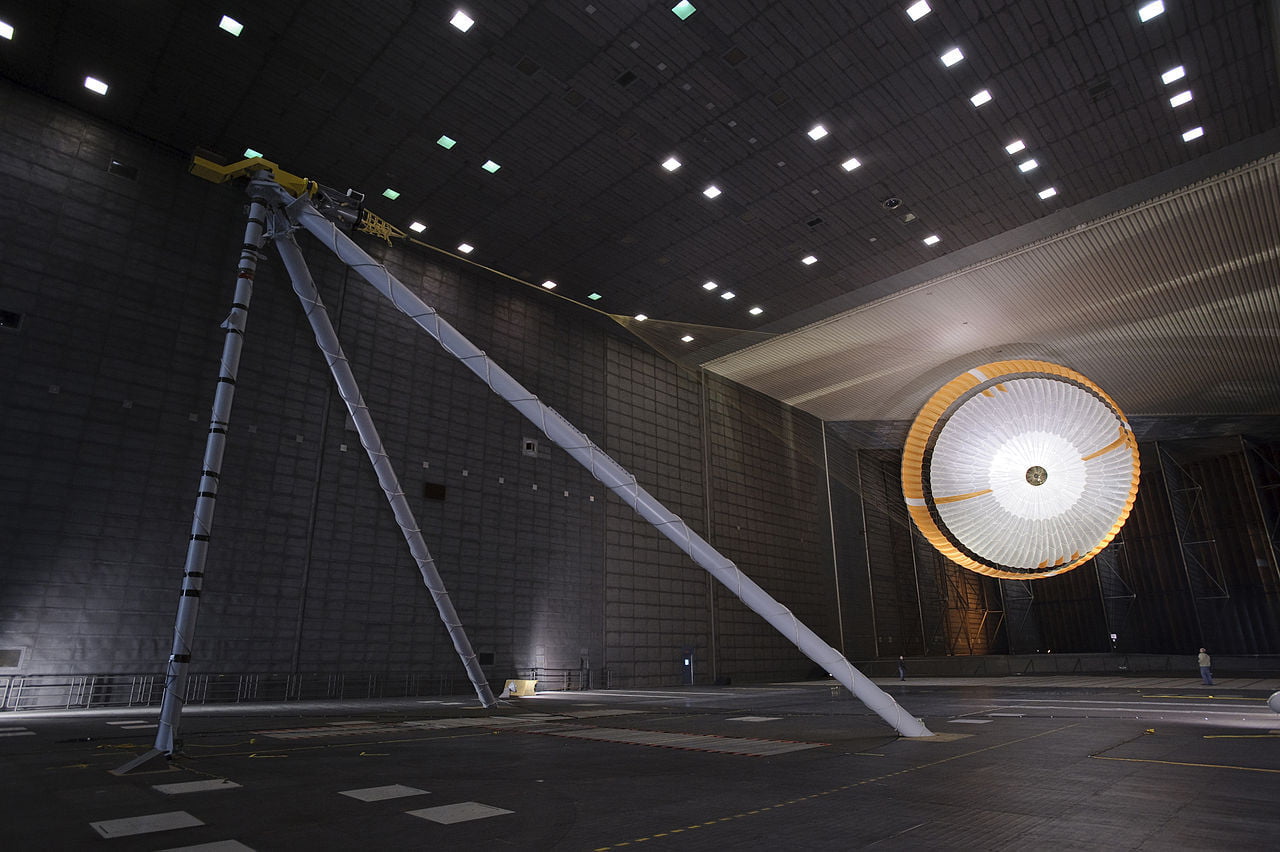

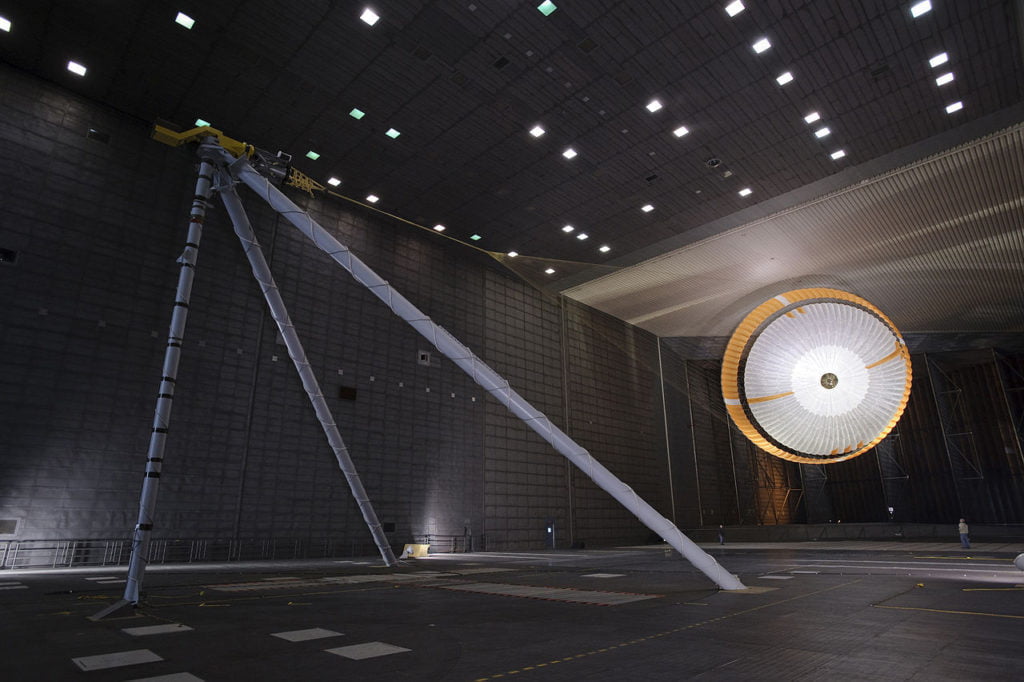

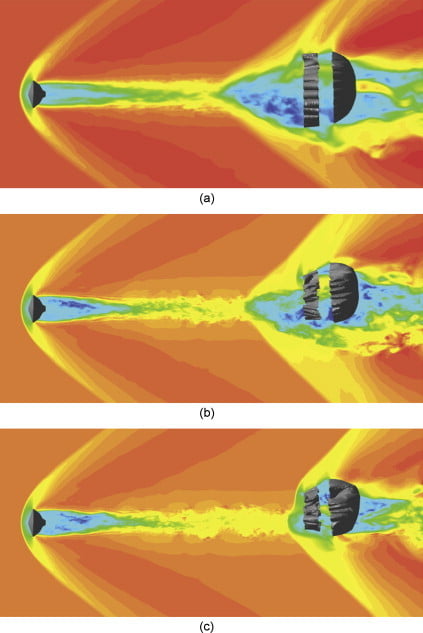

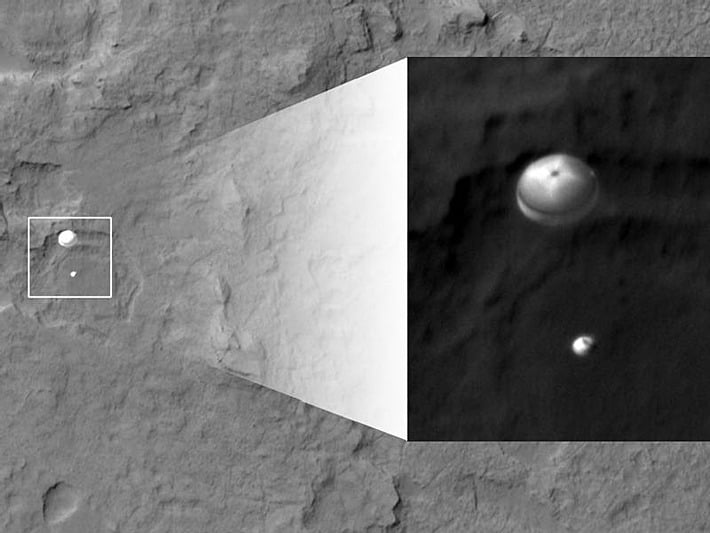

Martian Landing Physics

A little over a week ago, NASA’s Curiosity rover landed on Mars, the culmination of years of engineering. The mission’s landing, in particular, was the subject of intense scrutiny as Curiosity’s size necessitated some new techniques in the final segments of the landing sequence. As it hit the Martian atmosphere at 13,000 mph, the compression of the carbon dioxide behind the capsule’s shock wave slowed the descent. At roughly 1,000 mph–speeds still large enough to be supersonic–Curiosity deployed its parachute. Shown above are the parachute in numerical simulation (from Karagiozis et al. 2011), wind tunnel testing at NASA Ames, and during descent thanks to the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The simulation shows contours of streamwise velocity at different configurations; note the bow shock off the capsule and the additional shocks off the parachute. These help generate the drag needed to slow the capsule. For an interesting behind-the-scenes look at the wind tunnel testing for Curiosity’s parachute check out JPL’s four–part video series. Congratulations to all the scientists and engineers who’ve made the rover a success. We look forward to your discoveries! (Photo credits: K. Karagiozis et al., NASA JPL, NASA MRO)

Sally Ride

Today FYFD takes a brief aside from fluid dynamics to mark the passing of Sally Ride, the first U.S. woman to travel to space. A physicist by training, Ride served as a mission specialist on STS-7 and STS-41G, shuttle missions that included deploying satellites as well as conducting scientific experiments. After her career with NASA, Ride returned to physics as a faculty member at the University of California, San Diego and dedicated herself to motivating children and young adults–most especially women–to pursue careers in science, math, and engineering. She was an inspiration and role model to more than a generation; her courage and her passion for science touched many lives, including my own. Godspeed, Dr. Ride.

How the Sun Drives the Earth

This video describes how the sun’s energy drives wind and ocean currents on earth. As solar winds stream forth from the sun, our magnetosphere deflects the brunt of the impact (creating auroras at the poles) while the atmosphere, land masses, and oceans absorb thermal energy from the sun’s light. Because of our cycles of day and night and the differences in how land, water, and ice absorb heat, temperature differentials around the earth drive a massive heat engine, causing the circulation of water and wind all around our world. Numerical simulations like the ones underlying this video are vital for the prediction of climate and weather, as well as for developing models and techniques that can be applied to other problems in science and engineering. (Video credit: NASA; via Gizmodo)

Portrait of Gas Giants

[original media no longer available]

Here raw footage from NASA’s Cassini and Voyager missions has been combined in a stunning portrait of Saturn and Jupiter. Watch as tiny moons create gravity waves in the rings of Saturn and observe the complicated relative motion between the cloud bands on Jupiter and the swirls and vortices that result. Fluid dynamics are truly everywhere. (Video credit: Sander van den Berg; submitted by Daniel B)

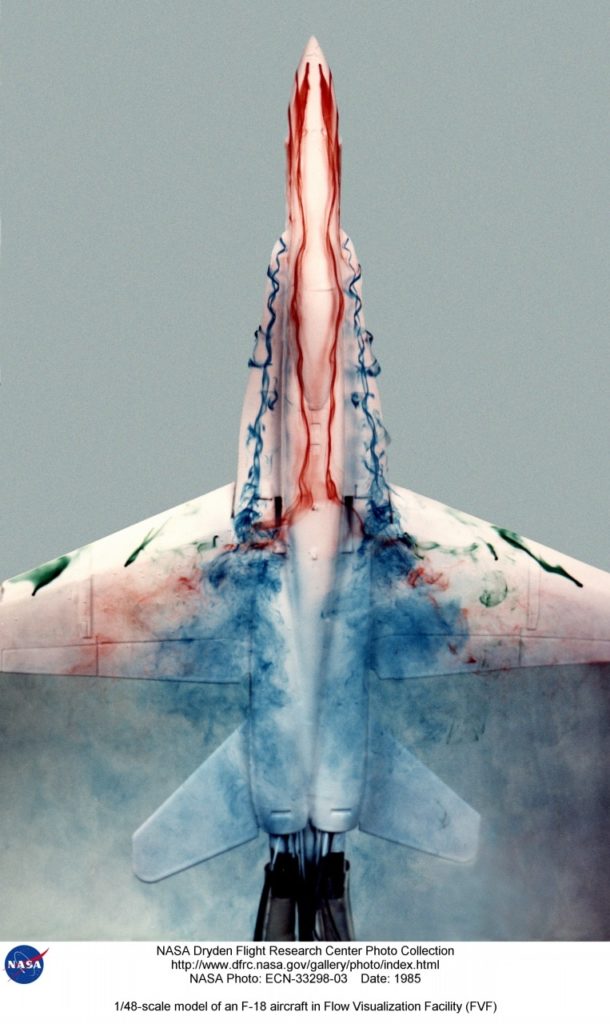

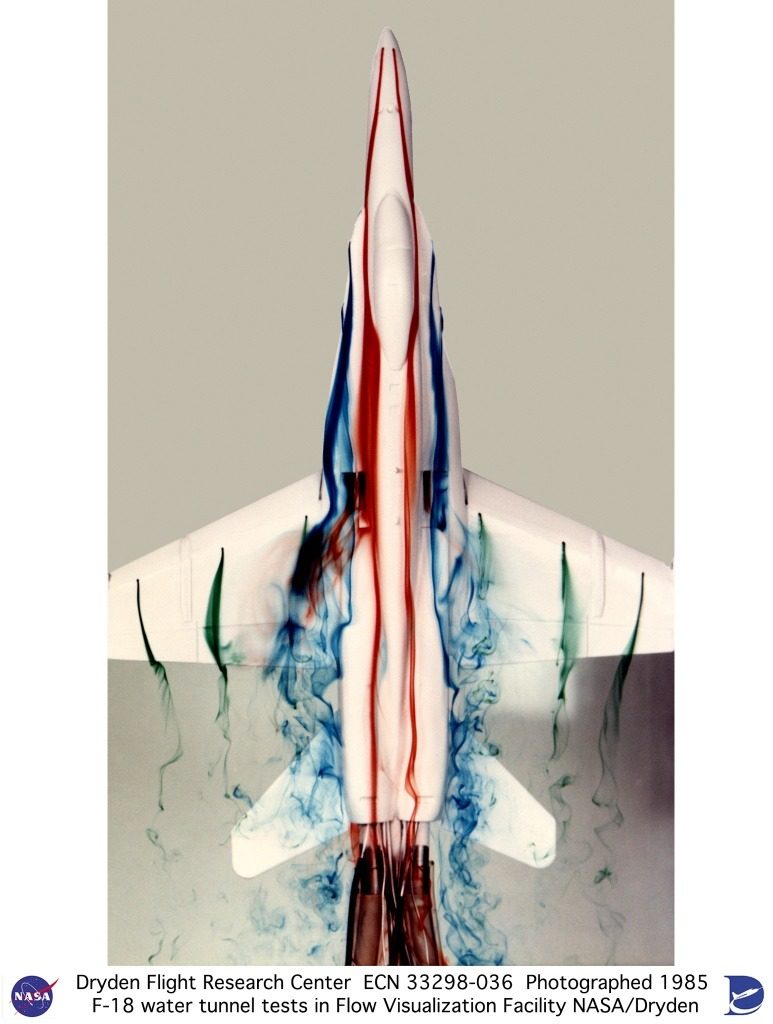

F-18 Flow Viz

Water tunnels are useful tools for determining aerodynamic characteristics of aircraft, such as this F-18 model placed in the NASA Dryden Flow Visualization Facility. By matching the Reynolds number of the model in the water tunnel to that of the full-scale aircraft in air, engineers can observe flow around the aircraft inside the laboratory. This similarity of flows is a powerful design tool. Here dye introduced along the nose, wings, and fuselage traces streamlines around the F-18, revealing areas of turbulence at different flight conditions.

Testing Flames in Space

In microgravity, flames behave very differently than on earth due to a lack of buoyant forces. On earth, a flame can continue burning because, as the warm air around it rises, cooler air gets entrained, drawing fresh oxygen to the flame. In microgravity, both the heat from the flame and the oxygen it needs to burn move only by molecular diffusion, the random motion of molecules, or the background environmental flow (air circulation on the ISS, for example). This video shows a test of the Flame Extinguishment Experiment (FLEX) currently flying onboard the ISS. A fuel droplet is ignited, burns in a symmetric sphere and then eventually extinguishes either due to a lack of fuel or a lack of oxygen. Check out this NASA press release for more, including great quotes like this:

“As a Princeton undergrad, I saw in a graduate course the conservation equations of combustion and realized that those equations were complex enough to occupy me for the rest of my life; they contained so much interesting physics.” – Forman Williams

Voyager Explores the Edge of the Solar System

Though unconventional by our terrestrial concepts of fluids, the solar wind and its interaction with objects in and around our solar system can be considered a form of fluid dynamics. This NASA video discusses discoveries made by the Voyager spacecrafts as they leave our solar system and pass into interstellar space. The solar wind, a rarefied stream of charged particles, streams outward from the Sun at supersonic speeds. Eventually, the pressure from the interstellar medium surrounding the solar system is sufficient to slow the solar wind to subsonic speeds, causing a termination shock much like the hydraulic jump that forms in a kitchen sink when you turn the faucet on.

Solar Flare

An M-class solar flare with a towering prominence erupted from the Sun over the course of three hours in late September. Notice how the plasma does not fall straight back to the surface but flows back down following the Sun’s magnetic field lines. As an rarefied ionized gas, plasma follows coupled laws of electromagnetism and fluid dynamics. #

Aurora from the ISS

The solar wind, a rarefied stream of hot plasma ejected from the sun, constantly bombards Earth’s magnetic field. This results in the formation of the magnetosphere, which deflects most of these charged particles away from the earth. Some of them, however, are drawn toward the magnetic poles; when these charged particles strike the upper atmosphere, they cause the gases there to release photons, resulting in the lights we know as auroras. This animation shows the International Space Station flying through the aurora australis–the southern lights. The fluid-like motion of the aurora is no accident; though diffuse, the solar wind is still a fluid governed by magnetohydrodynamics.