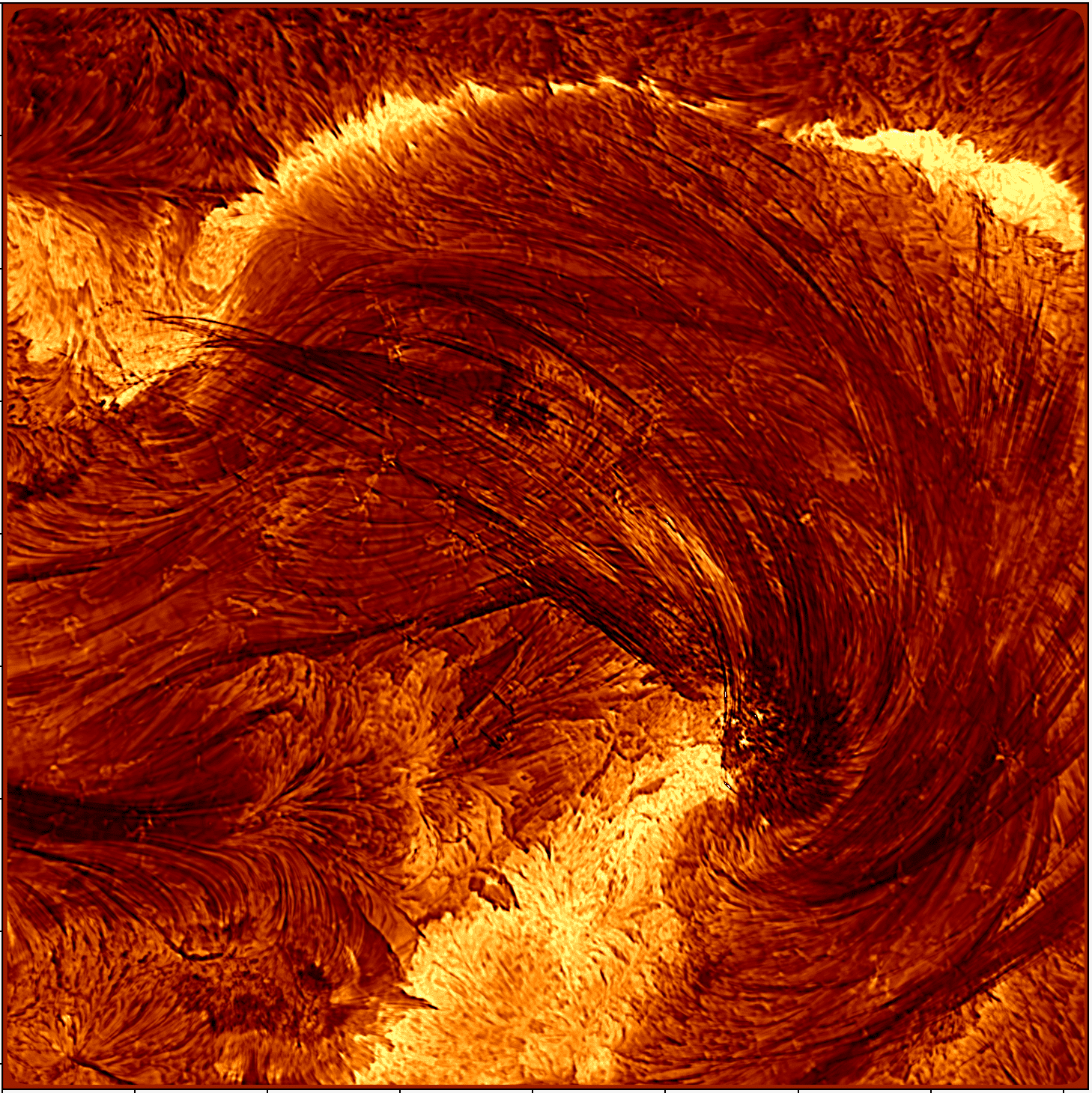

If you send a shock wave through a magnetized plasma–something that happens in both supernova explosions and inertial confinement fusion–it can trigger an instability known as the Richtmyer-Meshkov instability. The image above shows a form of this, taken from a simulation. Rather than treating the plasma as a single idealized fluid, the researchers represented it as two fluids: an ion fluid and an electron fluid. This allowed them to better capture what happens when certain components of the plasma react to changes faster than others do.

The image itself shows the electron number density across the fluid, where darker colors represent higher electron number density. The interface between high and low-densities shows a roll-up instability that resembles the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability, but there are also regions of mushroom-like plumes that more closely resemble Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities.

The authors note that these structures don’t appear in simulations that represent a plasma as a single fluid; you need the two-fluid representation to see them. (Image and research credit: O. Thompson et al.)