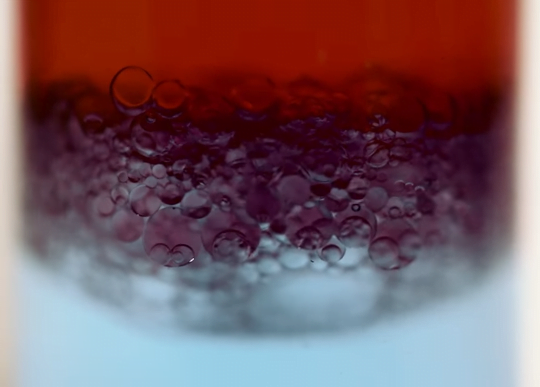

This colorful photo shows three fluids — oil, water, and dish soap — illuminated by the rainbow reflection of a CD. The differing densities of each fluid creates a stratification with water sandwiched between dish soap on the bottom and oil on the top. Because the dish soap is miscible in water, it leaves a smudgy blur against the background, whereas the immiscible oil creates bubble-like lenses at the top. (Image credit: R. Rodriguez)

Tag: miscibility

Popping an Oil Balloon

Oil and water don’t mix — or at least they won’t without a lot of effort! In this video, we get to admire just how immiscible these fluids are as oil-filled balloons get burst underwater.

Visually, the two bursts are quite spectacular. In the first image, the initial balloon has a sizeable air bubble at the top, which rises even more rapidly than the buoyant oil, creating a miniature, jelly-fish-like plume that reaches the surface first. The large oil plume follows, behaving similarly to the balloon burst without an added air bubble.

The last of the oil in both cases comes from a cloud of smaller droplets formed near the bottom of the balloon. Being smaller and less buoyant, these drops take a lot longer to rise to the surface and remain much closer to spherical as they do. I suspect these smaller droplets form due to the forces created by the fast-moving elastic as it tears away. (Video and image credit: Warped Perception)

The Birth of a Liquor

A water droplet immersed in a mixture of anise oil and ethanol displays some pretty complicated dynamics. Its behavior is driven, in part, by the variable miscibility of the three liquids. Water and ethanol are fully miscible, anise oil and ethanol are only partially miscible, and anise oil and water are completely immiscible. These varying levels of miscibility set up a lot of variations in surface tension along and around the droplet, which drives its stretching and eventual jump.

Once detached, the droplet takes on a flattened, lens-like shape that continues to spread. That spreading is driven by the mixing of ethanol and water, which generates heat and, thus, convection around the drop. This not only spreads the droplet, it causes turbulent behavior along the drop’s interface. (Image and video credit: S. Yamanidouzisorkhabi et al.)

Oil-on-Water Impact

Although many people have studied droplet impacts over the years, there’s been remarkably little work done with oil-on-water impacts. One of the things that makes this situation different is that the oil and water are completely immiscible, which means we can see aspects of the impact process that are invisible with, say, water-on-water impacts.

The animation above shows an underwater view of the oil droplet’s impact. The energy of the initial impact creates an expanding crater and an unstable crown splash. That crown splash contains both water and oil. After it ejects some droplets, the rim stabilizes, but we can still see small perturbations along its edge as it starts to retract. In the water, high surface tension damps out these perturbations. Not so for the oil! As the crater retracts, the small disturbances along the rim get stretched into mushroom-shaped fingers that point inward toward the impact site. Because the index of refraction is different between oil and water, we can see the fingers clearly near the end of the animation. (Image and research credit: U. Jain et al.; submitted by Utkarsh J.)

“Float”

In “Float” artist Susi Sie uses water and oil to create a whimsical landscape of bubbles and droplets. Coalescence is a major player in the action, though Sie uses some clever time manipulations to make her bubbles and droplets multiply as well. Watching coalescence in reverse feels like seeing mitosis happen before your eyes. (Video and image credit: S. Sie)

Sunset Flow

Day and night mix in this flow visualization of watercolor pigments and ferrofluid. The former, as suggested by their name, are water-based, whereas ferrofluids typically contain an oil base. This means the two fluids are immiscible. Like oil and vinegar in salad dressing, the only way to mix them is to break one into tiny droplets floating in the other. This is what happens near their boundary, where brightly-colored paint droplets float in a network of dark channels. To the right, the paint and ferrofluid have been swirled around to create viscous mixing patterns among the paint colors with occasional intrusions of thin ferrofluid fingers. (Image credit: G. Elbert)

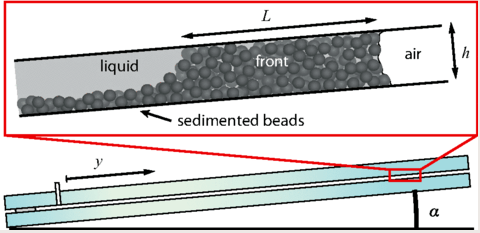

Flowing Through Tight Spaces

Fluid flow through porous media inside confined spaces can be tough to predict but is key to many geological and industrial processes. Here researchers examine a mixture of glass beads and water-glycerol trapped between two slightly tilted plates. As liquid is drained from the bottom of the cell, air intrudes. Loose grains pile up along the meniscus and get slowly bulldozed as the air continues forcing its way in. The result is a labyrinthine maze formed by air fingers of a characteristic width. The final pattern depends on a competition between hydrostatic pressure and the frictional forces between grains. Despite the visual similarity to phenomena like the Saffman-Taylor instability, the authors found that viscosity does not play a major role. For more, check out the video abstract here. (Image and research credit: J. Erikson et al., source)

Water Atop Oil

At first glance, this image looks much like the impact of any drop on a pool of the same liquid, but that’s not what you’re seeing. This is the impact of a water droplet on a thin film of oil, and the immiscibility of those two fluids has important effects on the collision. When the water drop impacts, it spreads and forms a compound crown that rises out of the fluid. Eventually, that momentum runs out and the crown falls into the liquid.

Water’s intermolecular forces are strong enough to pull the remains of the droplet back in on itself. As that fluid collides at the center, it gets forced up into a central jet with enough energy to eject a droplet or two at its tip. Even though this looks like a Worthington jet, it’s not. Worthington jets form after the collapse of a cavity in the impacted liquid – in other words, they form on pools, not on films. Despite the visual similarity, this central jet is formed entirely differently! (Image and research credit: Z. Che and O. Matar, source; submitted by O. Matar)

Emulsions By Condensation

Oil and water are hard to mix, as any salad dressing aficionado will attest. Technically, the two fluids are immiscible – they won’t mix with one another – but one way around this is to emulsify them by distributing droplets of one in the other. This is usually accomplished by shaking or using sound waves to vibrate the mixture, but the results are typically short-lived. The larger a droplet is, the more gravity affects it, causing the buoyant oil to rise and separate from the water.

The key to making an emulsion last is creating tiny droplets, which a new study accomplishes energy efficiently through condensation. Instead of mixing the oil and water immediately, the researchers used a surface covered in a mixture of oil and surfactant and cooled it in a humid chamber. As the temperature dropped, water condensed onto the oil and became encapsulated, creating nanoscale emulsion droplets. At such a tiny scale, buoyant forces are unable to overcome surface tension, so the emulsion remains stable for months. (Image credit: MIT, source; research credit: I. Guha et al.; via MIT News)

Equatorial Streaming

Here you see a millimeter-sized droplet suspended in a fluid that is more electrically conductive than it. When exposed to a high DC electric field, the suspended drop begins to flatten. A thin rim of fluid extends from the drop’s midplane in an instability called “equatorial streaming”. As seen in the close-up animation, the rim breaks off the droplet into rings, which are themselves broken into micrometer-sized droplets thanks to surface tension. The result is that the original droplet is torn into a cloud of droplets a factor of a thousand smaller. This technique could be great for generating emulsions of immiscible liquids–think vinaigrette dressing but with less shaking! (Image credit: Q. Brosseau and P. Vlahovska, source)