A raft of mosquito eggs floats on water in this award-winning image by Barry Webb. Capillary effects stretch and distort the interface, creating a complicated meniscus where the eggs meet the water. (Image credit: B. Webb from CUPOTY; via Gizmodo)

Tag: capillary action

Enhancing the Cheerios Effect

The Cheerios in your morning cereal clump together with one another and the bowl’s wall due to an attractive force caused by the curvature of their menisci. A recent study looks at how this effect changes when you’re pulling objects out of the liquid.

Snapshots show how two flexible fibers get drawn together by an attractive force as they are pulled out of silicon oil. The researchers inserted thin flexible glass fibers into silicon oil and withdrew them. As they did, they explored what lengths and retraction speeds caused the fibers to pull together. They found that a single moving rod had a taller meniscus than a stationary one, and two moving rods had a liquid bridge that superposed their individual menisci. The result was an attractive force even stronger than what the fibers experienced when still. (Image credit: Cheerios – D. Streit, experiment – H. Bense et al.; research credit: H. Bense et al.; via APS Physics)

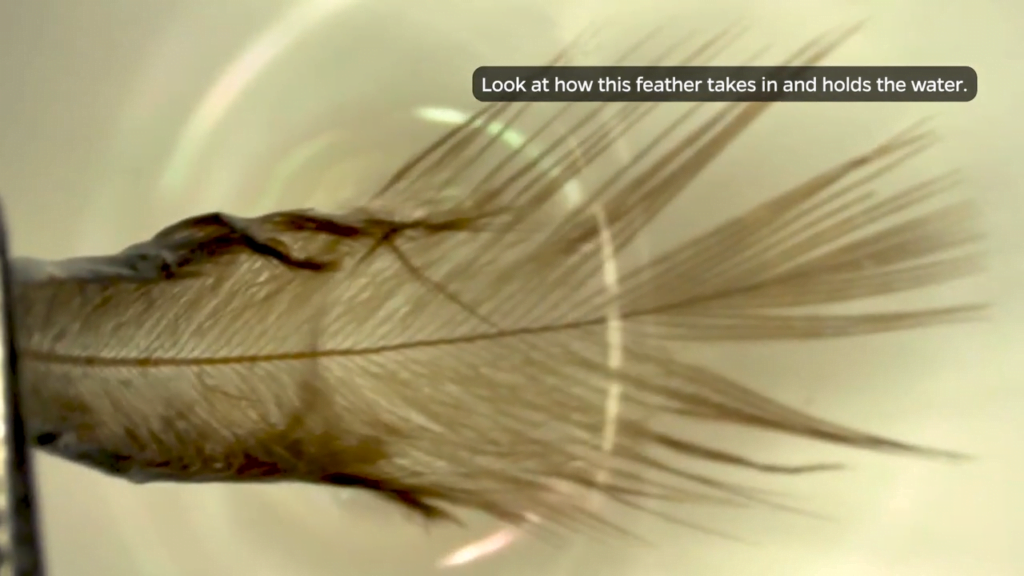

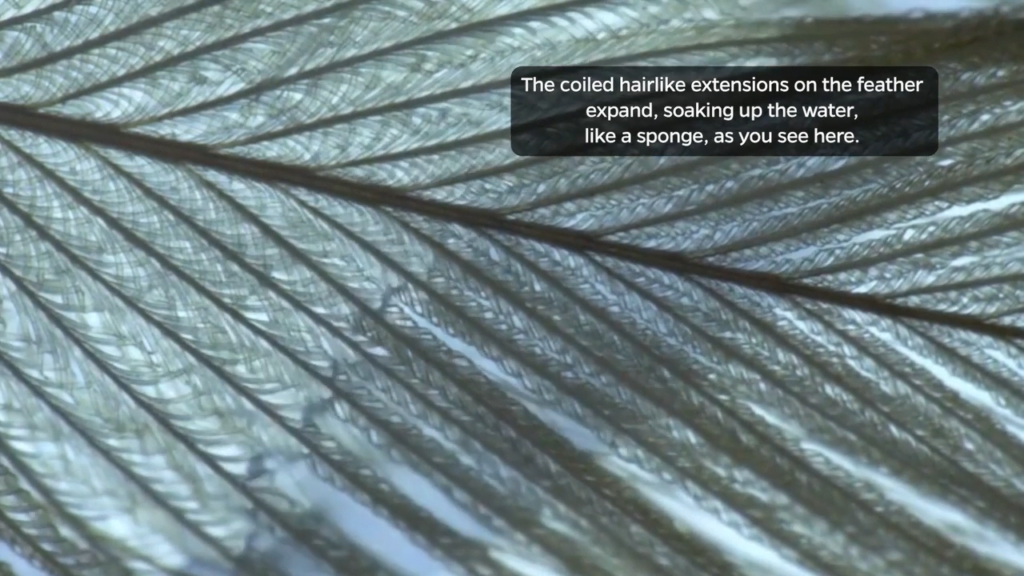

Sandgrouse Soak in Water

Desert-dwelling sandgrouse resemble pigeons or doves, but they have a very different superpower: males can soak in and hold 25 milliliters of water in their feathers, which they carry tens of kilometers back to their chicks. The key to this ability is the microstructure of the bird’s breast feathers. Unlike other species, where feathers have hooks and grooves that “zip” them together, the sandgrouse’s specialized feathers have tiny barbules with varying bending stresses. When dipped in water, their curled shape unwinds, allowing water to soak in through capillary action. Barbules at the tips curl inward, holding the water in place so that the sandgrouse can fly home with it.

Studying nature’s solutions for water-carrying will help engineers design better materials for human use, whether that’s a water bottle that avoids sloshing or a medical swab that’s better at absorbing and releasing fluids. (Image and video credit: Johns Hopkins; research credit: J. Mueller and L. Gibson; via Forbes; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Bending in Bubbles

Inside a cavity with a square cross-section, bubbles form an array. The shapes of their edges are determined by surface tension and capillarity (lower half of center image). Adding an elastic ribbon into the bubbles (upper half of center image) means that the bubbles’ shapes are determined by a competition between the elasticity of the ribbon and the capillarity of the fluid. Researchers found that they could tune the rigidity of the ribbon to dictate the shape of the bubble array, or, conversely, they could use the bubbles to set the shape of a UV-curable ribbon. (Image and research credit: M. Jouanlanne et al., see also)

Escaping the Flood

Fire ants clump together into giant rafts to stay alive during floods. But these rafts won’t form with just any number of ants. Researchers found that individual ants will actually kick one another away. It’s not until there are about ten ants that the raft formation becomes stable. In this video, the team lays out their experiments and models for fire ant rafting, showing that capillary action helps draw the raft together and individual ants’ activity can destabilize rafts if they’re too small. (Image and video credit: H. Ko and D. Hu)

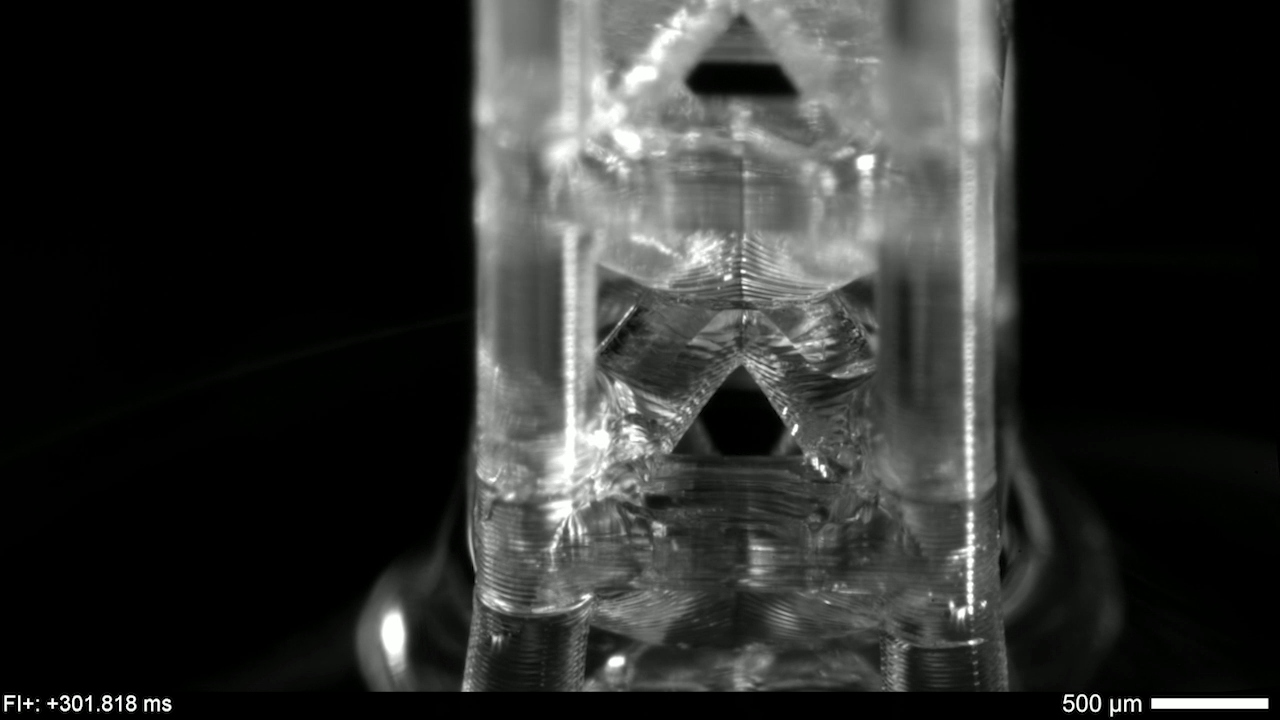

Programmable Capillary Action

Capillary action combines the cohesive forces within a liquid and the adhesive forces between a liquid and solid to enable a liquid to fill narrow spaces, even against the force of gravity. To control capillary action, researchers are 3D-printing what they call “unit cells,” tiny structures that water and other liquids can climb. There’s no pump raising the liquid through these structures, just capillary action.

In a particularly neat demonstration of the technology, the researchers built a tree-like structure out of many open-walled unit cells and placed the “root” system in a closed reservoir. Capillary action drew liquid up the structure to the tips of its branches, where the dyed water evaporated. The process is similar to transpiration in trees, though in trees, capillary action provides much less of the lift. (Image and research credit: N. Dudukovic et al.; via Nature; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Why Aren’t Trees Taller?

Trees are incredible organisms, with some species capable of growing more than 100 meters in height. But how do trees get so big and why don’t they grow even taller? The limit, it turns out, is how far fluid forces can win over gravity.

To live and grow, trees must be able to transport nutrients between their roots and their highest branches. As explained in the video, there are three forces that enable this transport inside trees: transpiration, capillary action, and root pressure. Of these, you are probably most familiar with capillary action, where intermolecular forces help liquids climb up the inside of narrow spaces, like the straw in your drink. Capillary action can’t lift liquids more than a few centimeters against gravity, though.

Similarly, root pressure is limited in how far it can raise liquids. Functionally, it’s pretty similar to the way a column of water or mercury can be held up by atmospheric pressure acting at the base of a barometer. But atmospheric pressure can only hold up 10.3 meters of water, so what’s a tree to do?

This is where transpiration — the most important force for sap transport in the tree — comes in. As water evaporates out of the tree’s leaves, it creates negative pressure that — along with water’s natural cohesion — literally drags sap up from the roots. It’s this massive pull that drives the flow and enables most of a tree’s height. (Image and video credit: TED-Ed)

Particle-filled Splashes

Adding particles to a liquid can significantly alter its splash dynamics, as shown in this new study. In the first image, a purely-liquid droplet spreads on impact into a thin liquid sheet that destabilizes from the rim inward, ripping itself into a spray of droplets. At first glance, the particle-filled droplet in the second image behaves similarly; it, too, spreads and then disintegrates. But there are distinctive differences.

During expansion, the particles increase the drop’s effective viscosity, meaning that the splash sheet does not expand as far. That apparent viscosity increase is also part of why the drops the splash sheds are bigger than those without particles. The other part of that story comes from the retraction, where the variations in thickness caused by the particles and their menisci create preferential paths for the flow. As a result, the particle-filled splash breaks up faster and into larger droplets compared to its purely-liquid counterpart. (Image and research credit: P. Raux et al.)

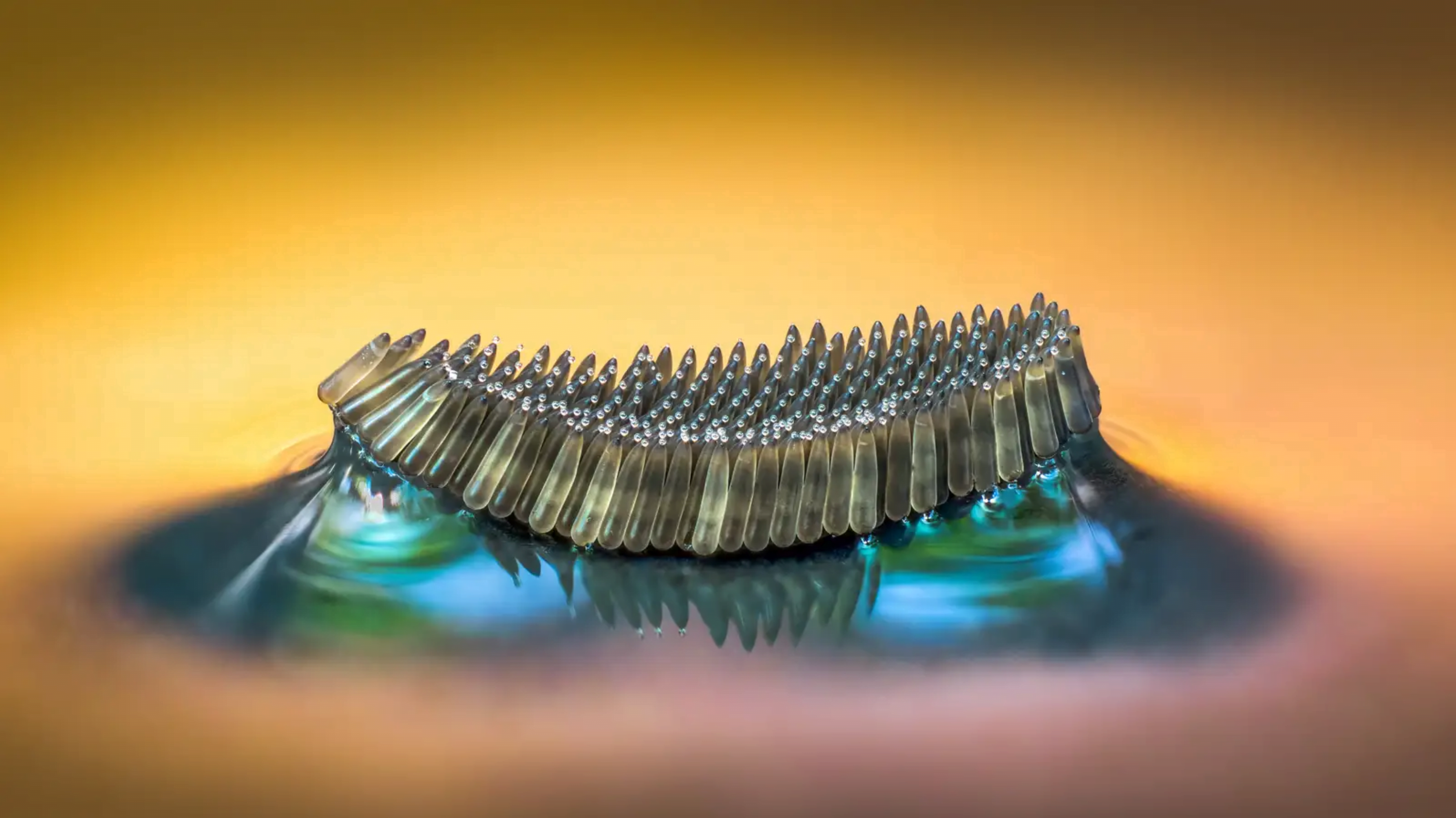

Breaking Up Granular Rafts

Particles at a fluid interface will often gather into a collection known as a granular raft. The geometry of the interface where it meets individual particles, combined with the surface tension, creates the capillary forces that attract these particles to one another. Colloquially, this is called the Cheerio’s effect; it’s the same physics that draws those cereal chunks together in your bowl.

Once together, these granular rafts can be surprisingly difficult to break up. That’s the focus of a new study on erosion in granular rafts. As seen in the top image, the raft has to be moving quite quickly before individual beads get pulled away. The experimental set-up here is pretty neat, and it’s not apparent from the video, so I’ll take a moment to explain it. The particles you see are gathered at an interface between water and oil. To generate the movement we see, researchers take the metal cylinder seen at the left of the image and pull it downward. That curves the oil-water interface, effectively creating a hill for the raft to accelerate down.

To focus in on the forces necessary to separate individual particles, the researchers also looked at a pair of particles (bottom image). With this set-up, they could more easily track the geometry of the contact line where the oil, water, and bead meet. What they found is that the attractive forces generated between the beads are two orders of magnitude larger than predicted by classical theory. To correctly capture the effect, they needed a far more precise description of the contact line geometry around a sphere than is typically used. (Image and research credit: A. Lagarde and S. Protière)

The Disappearing Cotton Candy

Moisture is cotton candy’s natural enemy. The spun sugar dissolves incredibly quickly under the influence of even a couple drops of water. Why that’s so is clearer when looking at a single fiber. Inside the droplet there’s a gradient in the sugar concentration. The more sugary water sinks, and the sugar fiber dissolves more quickly in the upper part of the droplet, where the less sugary water can more easily take up new sugar.

Once the fiber breaks, capillary forces draw the droplet upward, giving it a fresh section of fiber to dissolve. In a web of fibers, this process can pull droplets apart and together as they quickly eat through the spun sugar. (Image and video credit: S. Dorbolo et al.; submitted by Alexis D.)