At high, dry altitudes, fields of snow transform into rows of narrow, blade-like formations as tall as 2 meters. Known as penitentes – due to their similarity to kneeling worshipers – these surreal snow sculptures form primarily due to solar reflection. Surrounded by dry air and intense sunlight, the snow tends to sublimate directly into water vapor rather than melt into water. This turns an initially flat snowfield into one randomly dotted with little depressions. The curved surface of those depressions helps reflect incoming sunlight, causing the indentations to grow deeper and deeper over time. Although the high Andes are best known for their penitentes, they form elsewhere as well. Recent work has even identified them on Pluto! (Image credit: G. Hüdepohl; research credit: M. Betterton)

Tag: geophysics

Tornadoes, Fire, and Ice

It’s time for another look at breaking fluid dynamics research with the latest FYFD/JFM video! This time around, we tackle some geophysical fluid dynamics, like listening to the sounds newborn tornadoes make below the range of human hearing; studying how melting ice affects burning oil spills; and how salt sinking from sea ice affects the ocean circulation. Check out the full video below for much more! If you’ve missed any of the previous videos in the series, you can check them out here. (Image and video credit: T. Crawford and N. Sharp)

Waves Below the Surface

Even a seemingly calm ocean can have a lot going on beneath the surface. Many layers of water at different temperatures and salinities make up the ocean. Both of those variables affect density, and one stable orientation for the layers is with lighter layers sitting atop denser ones. Any motion underwater can disturb the interface between those two layers, creating internal waves like the ones in this demo. In the actual ocean, these internal waves can be enormous – 800 meters or more in height! In regions like the Strait of Gibraltar where flowing tides encounter underwater topography, large internal waves are a daily occurrence. Internal waves can also show up in the atmosphere and are sometimes visible as long striped clouds. (Video and image credit: Cal Poly)

Kilauea’s Lava Lake

Hawaii’s Kilauea Volcano continues to erupt, sending magma flowing through multiple fissures. The U.S. Geological Survey has sounded a warning, however, that the volcano could erupt more explosively. Hot spot volcanoes like Hawaii’s generally have more basaltic lava, which has a lower viscosity than more silica-rich magmas like those seen on continental plates. That makes Hawaii’s volcanoes less prone to explosive detonations like the 1980 Mt. St. Helens eruption. With less viscous lava, there’s less likelihood of plugging a magma chamber and causing a deadly buildup of pressure from toxic gases.

But that doesn’t mean that there’s no risk. In particular, officials are concerned by the rapid draining of a lava lake near Kilauea’s summit. As illustrated below, if the lava level drops below the water table, that increases the likelihood of steam forming in the underground chambers through which lava flows. The rapid drainage has destabilized the walls around the lava lake, causing frequent rockfalls into the chamber. If those were to plug part of the chamber and cause a steam buildup, then there could be an explosive eruption that releases the pressure. To be clear: even if this were to happen, it would be nothing like the explosiveness of Mt. St. Helens. But it would include violent expulsions of rock and widespread ash-fall. (Image credits: USGS, source; via Gizmodo)

Crevasses

Glacial ice is constantly flowing but at speeds we don’t notice by eye. That doesn’t mean there aren’t signs, though! Crevasses, narrow fractures in the ice that may be tens of meters deep, are a sign of those flows. Crevasses form in areas where the ice is under high stress. That could be a spot where the ice is flowing down a steeper incline or a place where multiple ice flows merge. Researchers can even use ice-penetrating radar to locate buried crevasses deep inside the ice. These are remnants of past flow conditions and provide hints at how the ice flows have changed over time. Crevasses are also a path for meltwater to penetrate deep into the ice, which can change slip conditions at the base of the glacier and increase both flow and melt rates. (Image credit: NASA/Digital Mapping Survey; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Mediterranean Currents

Ocean currents play a major role in the weather and climate of our planet. This video shows a simulation of the surface ocean currents in the Mediterranean and Atlantic over an 11-month period. Each second corresponds to 2.75 days. You’ll see many swirling eddies in the Mediterranean and more flow along the coastlines in the Atlantic. One observation worth noting: near the end of the video, you’ll notice that flow through the Strait of Dover between England and France changes its direction, flowing back and forth depending on tidal forces. In contrast, flow through the Strait of Gibraltar is always into the Mediterranean (within the timescale of the simulation, at least). This net in-flow to the Mediterranean is due in part to the warm waters there evaporating at a higher rate than the cooler Atlantic. (Video credit: NASA; via Flow Viz; h/t to Ralph L)

Upcoming Webcast

This weekend I’ll be holding my second live webcast for FYFD patrons. This month we’ll be focusing on the subject of planetary science, one of the coolest applications out there for fluid dynamics. My guests will be Keri Bean, a NASA JPL mission operations engineer and atmospheric scientist, and Professor Geoffrey Collins, a geologist at Wheaton College in Massachusetts. Keri has worked on all the recent Martian missions, including Mars Curiosity and the Phoenix Lander. She currently works on operations for the Dawn mission to Ceres. Geoff studies the geophysics of icy planets and moons like Pluto and Titan. He was part of the Galileo and Cassini missions to Jupiter and Saturn and is currently part of the team working on a future mission to Europa.

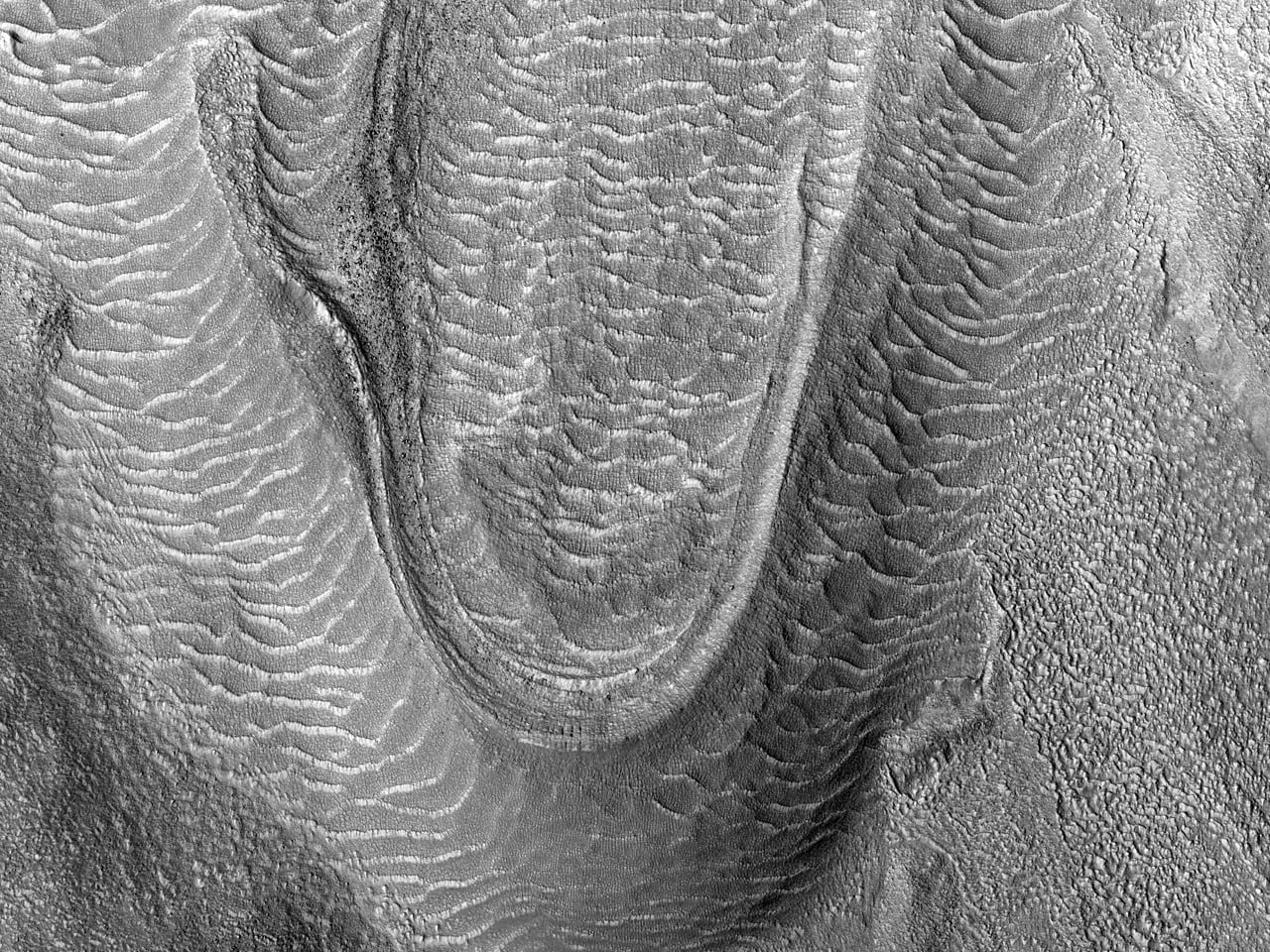

Martian Viscous Flow

These images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter show what are called viscous flow features. They are the Martian equivalent of glacial flow. Such features are typically found in Mars’ mid-latitudes.

Ground-penetrating radar studies of Mars have shown that some of these features contain water ice covered in a protective layer of rock and dust, making them true glaciers. Another study of similar Martian surface features found that their slope was consistent with what could be produced by a ~10 m thick layer of ice and dust flowing superplastically over a timescale equal to the estimated age of the surface features. Superplastic flow occurs when solid matter is deformed well beyond its usual breaking point and is one of the common regimes for glacial ice flow on Earth. (Image credit: NASA/JPL/U. of Arizona; via beautifulmars)

Pyroclastic Flow

Major volcanic eruptions can be accompanied by pyroclastic flows, a mixture of rock and hot gases capable of burying entire cities, as happened in Pompeii when Mt. Vesuvius erupted in 79 C.E. For even larger eruptions, such as the one at Peach Spring Caldera some 18.8 million years ago, the pyroclastic flow can be powerful enough to move half-meter-sized blocks of rock more than 150 km from the epicenter. Through observations of these deposits, experiments like the one above, and modeling, researchers were able to deduce that the Peach Spring pyroclastic flow must have been quite dense and flowed at speeds between 5 – 20 m/s for 2.5 – 10 hours! Dense, relatively slow-moving pyroclastic flows can pick up large rocks (simulated in the experiment with large metal beads) both through shear and because their speed generates low pressure that lifts the rocks so that they get swept along by the current. (Image credit: O. Roche et al., source)

Glaciers in Motion

To the naked eye, glaciers don’t appear to move much, but appearances can be deceiving. Like avalanches and turbidity currents, glaciers flow under the influence of gravity. They typically move at speeds around 1 meter per day, but some glaciers, like those shown above in Pakistan’s Central Karakorum National Park, can briefly surge to speeds a thousand times higher than their usual. The animation above shows 25 years worth of Landsat satellite imagery, enabling one to more easily observe the motion of these slow giants. Try picking out a feature along one of the glaciers and watch it move year-by-year. The glaciers just right of the image centerline are some of the best! (Image credit: J. Allen; via NASA Earth Observatory; submitted by Vince D)

Enjoy FYFD? Consider becoming a patron to help support the site!