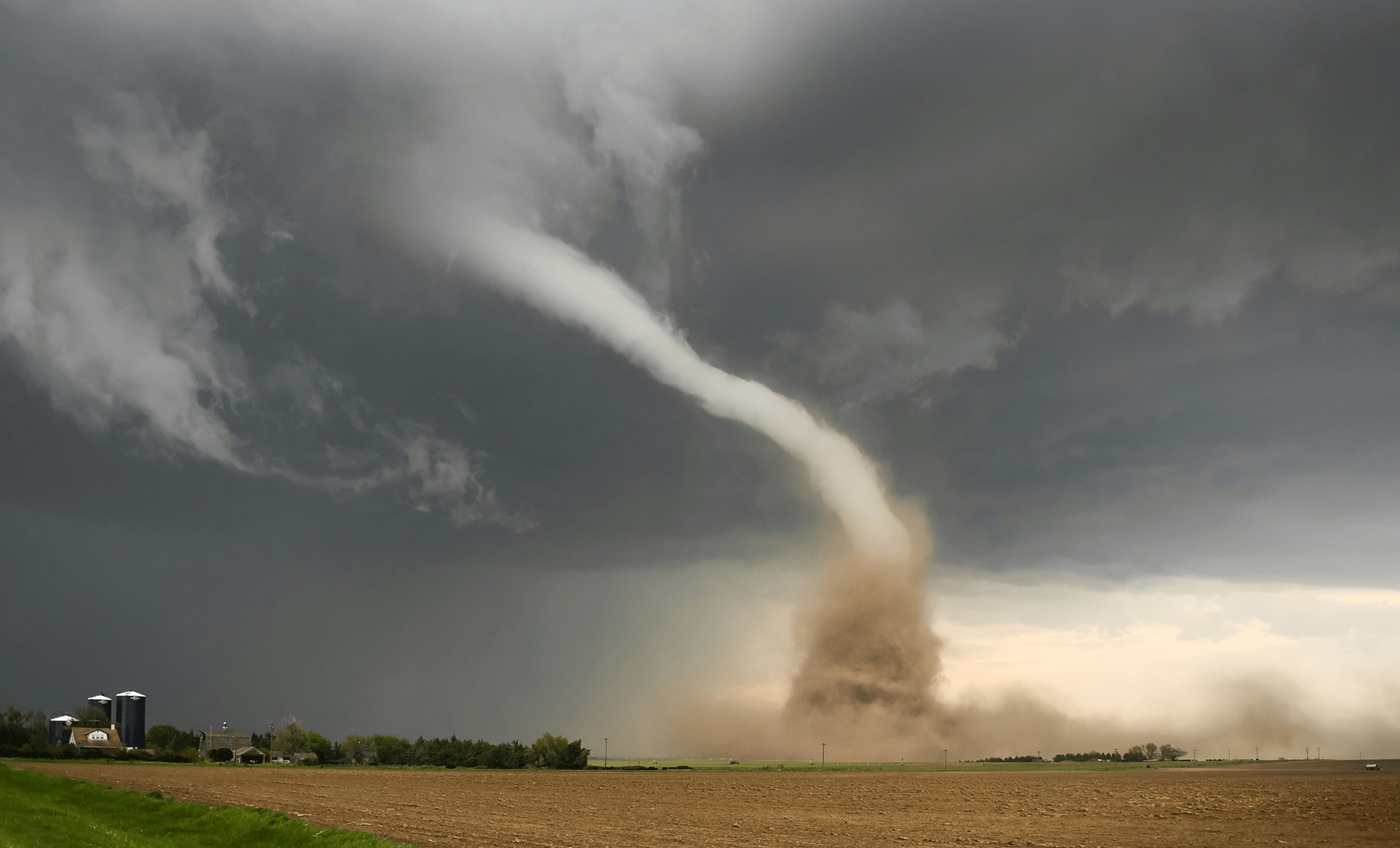

Growing up in northwest Arkansas, I spent my share of summer nights sheltering from tornadoes. Central North America — colloquially known as Tornado Alley — is especially prone to violent thunderstorms and accompanying tornadoes. That’s due, in part, to two geographical features: the Rocky Mountains and the Gulf of Mexico. Trade winds hitting the eastern slope of the Rockies get turned northward, imparting a counterclockwise vorticity. At the same time, warm moist air carried from the Gulf feeds into the atmosphere, creating perfect conditions for powerful thunderstorms. By this logic, though, South America should see lots of tornadoes, too, courtesy of the Andes Mountains and the moist environs of the Amazon Basin. To understand why South America doesn’t have a Tornado Alley, researchers used global weather models to investigate alternate North and South Americas.

They found that smoothness is a key ingredient for the upstream, moisture-generating region. Compared to the Amazon, the Gulf of Mexico is incredibly flat. With a flat Gulf, tornadoes abounded in North America, but their numbers dropped once that area was roughened to mimic the Amazon. The opposite held true, too: a smoothed-out Amazon Basin resulted in more simulated South American tornadoes.

For those in Tornado Alley, the results don’t offer much hope for mitigating our summer storms — we can’t exactly roughen the ocean. But the study does sound a word for warning for South America; the smoother the Amazon region becomes — due to mass deforestation — the more likely tornadoes become in parts of South America. (Image credit: G. Johnson; research credit: F. Li et al.; via Physics World)