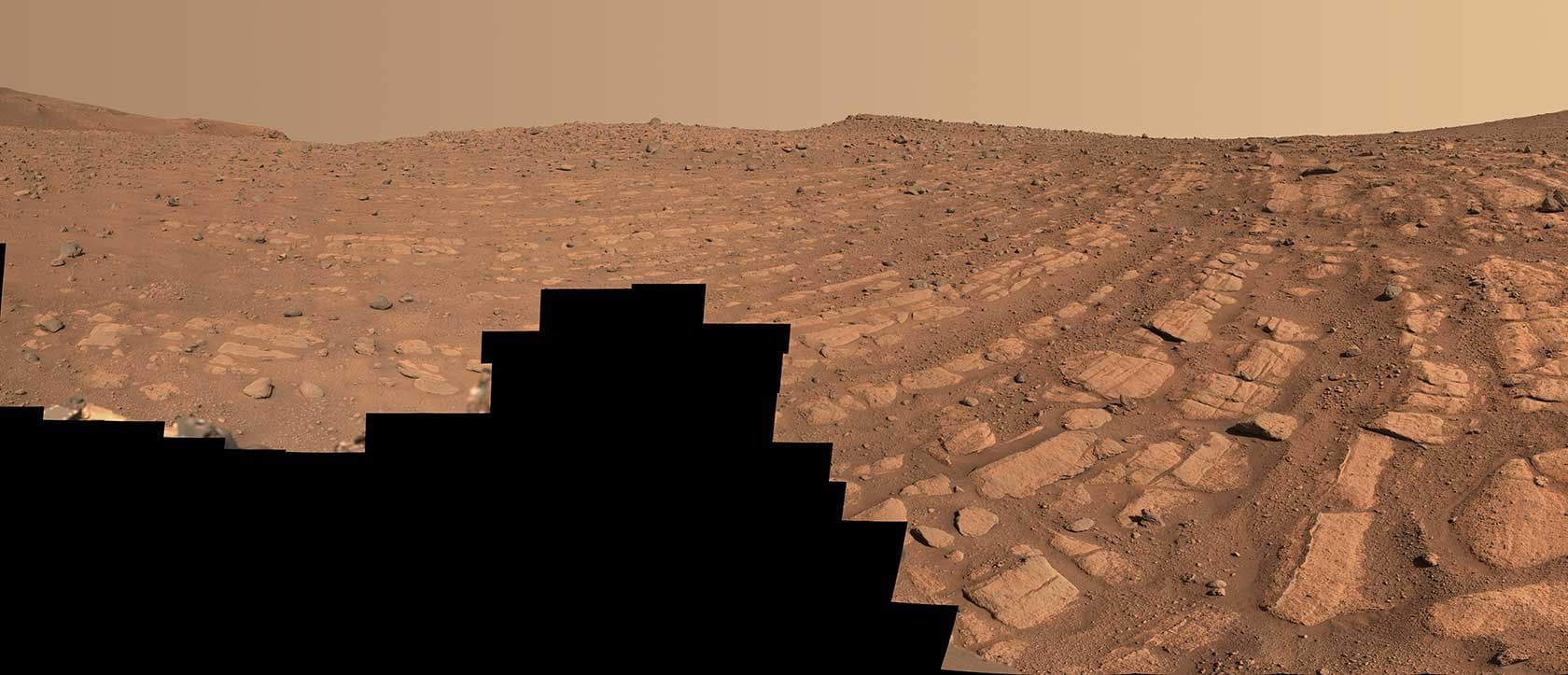

The surface features of Mars — crossed by river deltas and sedimentary deposits — indicate a watery past. Where that water went after the planet lost its atmosphere 3 – 4 billion years ago is an open question. But a new study suggests that quite a bit of that water moved underground rather than escaping to space.

The research team analyzed seismic data from the Mars InSight Lander. Marsquakes and meteor strikes on the Red Planet send seismic waves through the planet’s interior. The waves’ speed and other characteristics change as they pass through different materials, and by comparing different waves picked up from the same originating source, scientists can back out what the waves passed through on the way to the detector. In this case, the team concluded that the data best fit a layer of water-filled fractured igneous rock 11.5 – 20 kilometers below the surface. They estimate that the water trapped in this subsurface layer is enough to cover the surface of the planet in a 1 – 2 kilometer deep ocean. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech; research credit: V. Wright et al.; via Physics World)