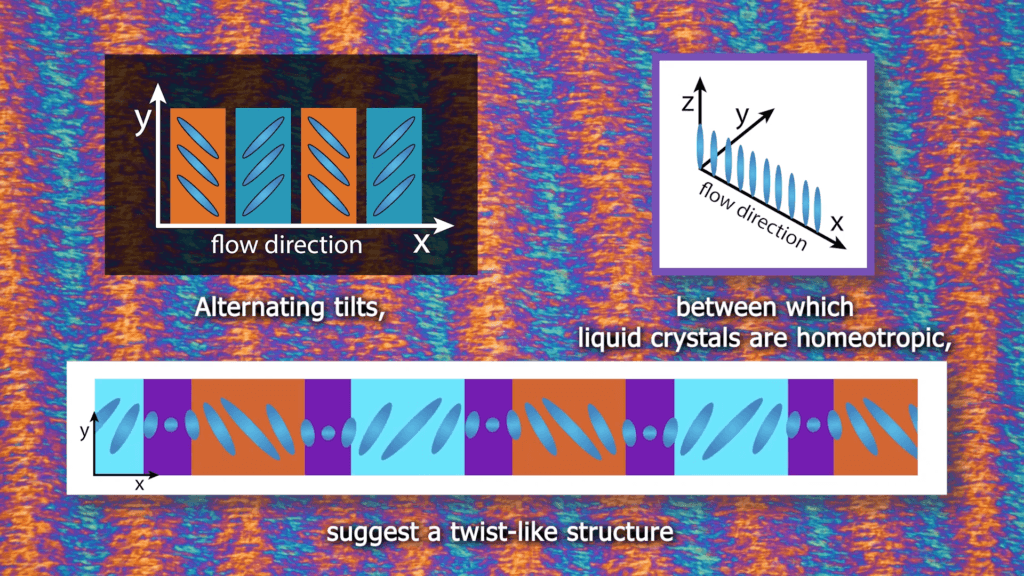

What happens to liquid crystals in a flow? In this video, researchers look at liquid crystals flowing through the narrow gap of a microfluidic device. Initially, all the crystals are oriented the same way, as if they are logs rolling down a river. But as the flow rate increases, narrow lines appear in the flow, followed by disordered regions, and, eventually, a new configuration: vertical bands streaking the left-to-right flow. The colors, in this case, indicate the orientation of the liquid crystals. As the researchers show, the crystals collectively twist to form the spontaneous bands. (Video and image credit: D. Jia and I. Bischofberger)

Tag: flow visualization

Simulating a Sneeze

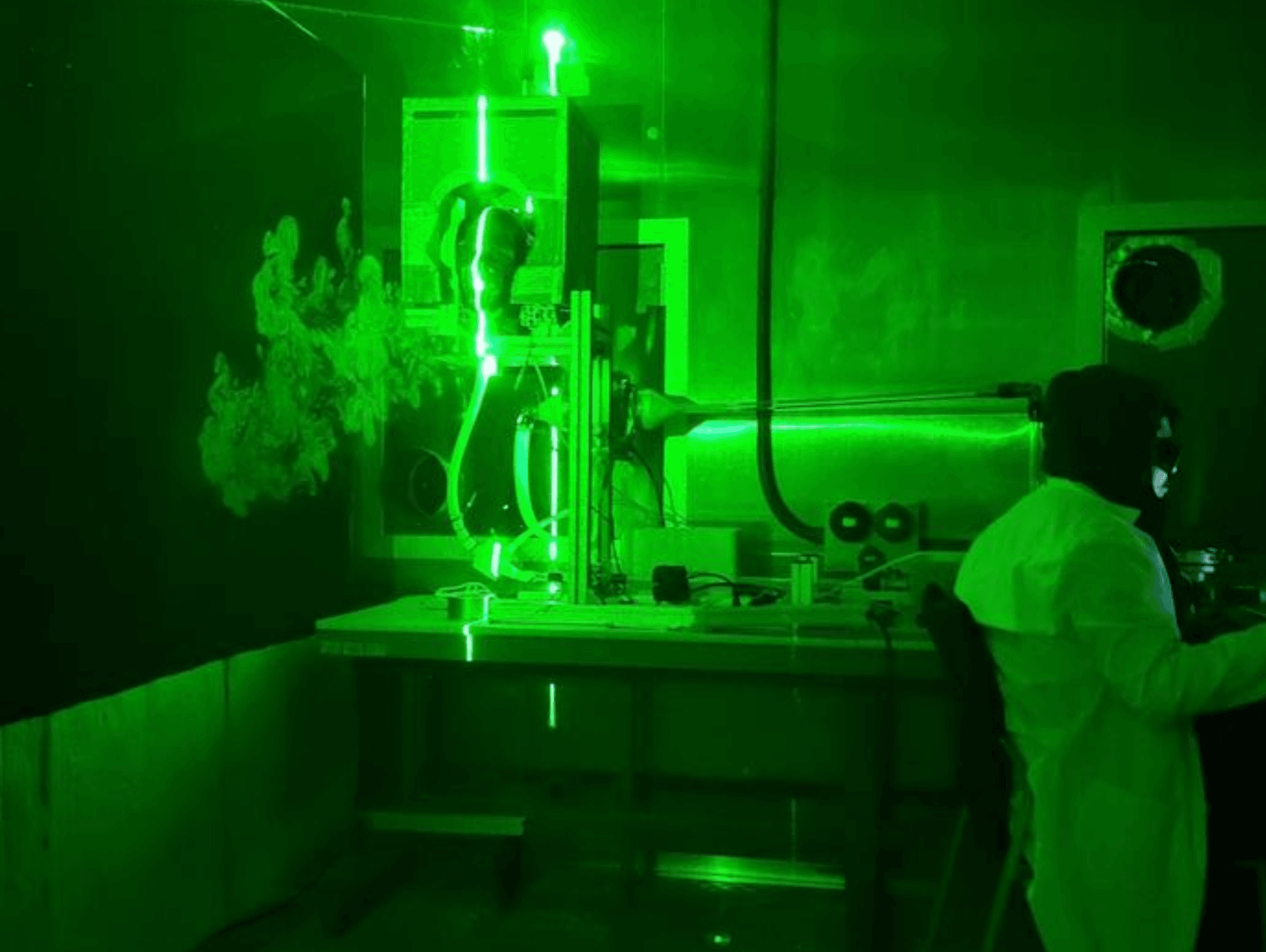

Sneezing and coughing can spread pathogens both through large droplets and through tiny, airborne aerosols. Understanding how the nasal cavity shapes the aerosol cloud a sneeze produces is critical to understanding and predicting how viruses could spread. Toward that end, researchers built a “sneeze simulator” based on the upper respiratory system’s geometry. With their simulator, the team mimicked violent exhalations both with the nostrils open and closed — to see how that changed the shape of the aerosol cloud produced.

The researchers found that closed nostrils produced a cloud that moved away along a 18 degree downward tilt, whereas an open-nostril cloud followed a 30-degree downward slope. That means having the nostrils open reduces the horizontal spread of a cloud while increasing its vertical spread. Depending on the background flow that will affect which parts of a cloud get spread to people nearby. (Image and research credit: N. Catalán et al.; via Physics World)

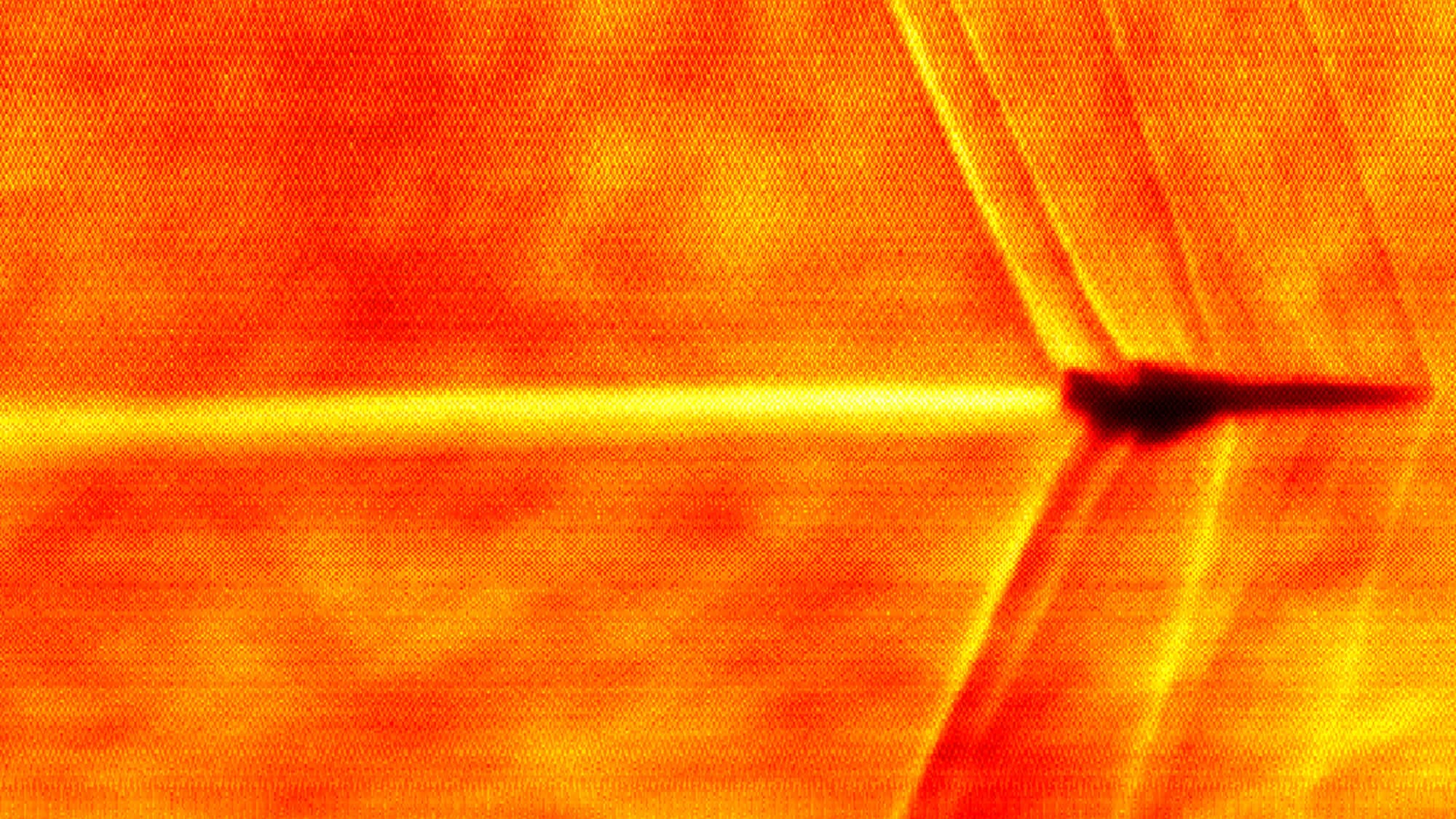

Imaging a New Era of Supersonic Travel

Supersonic commercial travel was briefly possible in the twentieth century when the Concorde flew. But the window-rattling sonic boom of that aircraft made governments restrict supersonic travel over land. Now a new generation of aviation companies are revisiting the concept of supersonic commercial travel with technologies that help dampen the irritating effects of a plane’s shock waves.

One such company, Boom Supersonic, partnered with NASA to capture the above schlieren image of their experimental XB-1 aircraft in flight. The diagonal lines spreading from the nose, wings, and tail of the aircraft mark shock waves. It’s those shock waves’ interactions with people and buildings on the ground that causes problems. But the XB-1 is testing out scalable methods for producing weaker shock waves that dissipate before reaching people down below, thus reducing the biggest source of complaints about supersonic flight over land. (Image credit: Boom Supersonic/NASA; via Quartz)

Salt Affects Particle Spreading

Microplastics are proliferating in our oceans (and everywhere else). This video takes a look at how salt and salinity gradients could affect the way plastics move. The researchers begin with a liquid bath sandwiched between a bed of magnets and electrodes. Using Lorentz forcing, they create an essentially 2D flow field that is ordered or chaotic, depending on the magnets’ configuration. Although it’s driven very differently, the flow field resembles the way the upper layer of the ocean moves and mixes.

The researchers then introduce colloids (particles that act as an analog for microplastics) and a bit of salt. Depending on the salinity gradient in the bath, the colloids can be attracted to one another or repelled. As the team shows, the resulting spread of colloids depends strongly on these salinity conditions, suggesting that microplastics, too, could see stronger dispersion or trapping depending on salinity changes. (Video and image credit: M. Alipour et al.)

Ultra-Soft Solids Flow By Turning Inside Out

Can a solid flow? What would that even look like? Researchers explored these questions with an ultra-soft gel (think 100,000 times softer than a gummy bear) pumped through a ring-shaped annular pipe. Despite its elasticity — that tendency to return to an original shape that distinguishes solids from fluids — the gel does flow. But after a short distance, furrows form and grow along the gel’s leading edge.

Front view of an ultra-soft solid flowing through an annular pipe. The furrows forming along the face of the gel are places where the gel is essentially turning itself inside out. Since the gel alongside the pipe’s walls can’t slide due to friction, the gel flows by essentially turning itself inside out. Inner portions of the gel flow forward and then split off toward one of the walls as they reach the leading edge. This eversion builds up lots of internal stress in the gel, and furrowing — much like crumpling a sheet of paper — relieves that stress. (Image and research credit: J. Hwang et al.; via APS News)

A Drop’s Shape Effects

Falling raindrops get distorted by the air rushing past them, ultimately breaking large droplets into many smaller ones. This research poster shows how variable this process is by showing two different raindrops, both of the same 8-mm initial diameter. On the left, the drop is prolate — longer than it is wide — and on the right, the drop is oblate — wider than it is long. Moving from bottom to top, we see a series of snapshots of each drop’s shape as it deforms and, eventually, breaks into smaller drops. The overall process is similar for each: the drop flattens, dimples, and then inflates like a sail, with part of the drop thinning into a sheet and ultimately breaking into smaller droplets. Yet, each drop’s specific details are entirely different. (Image credit: S. Dighe et al.)

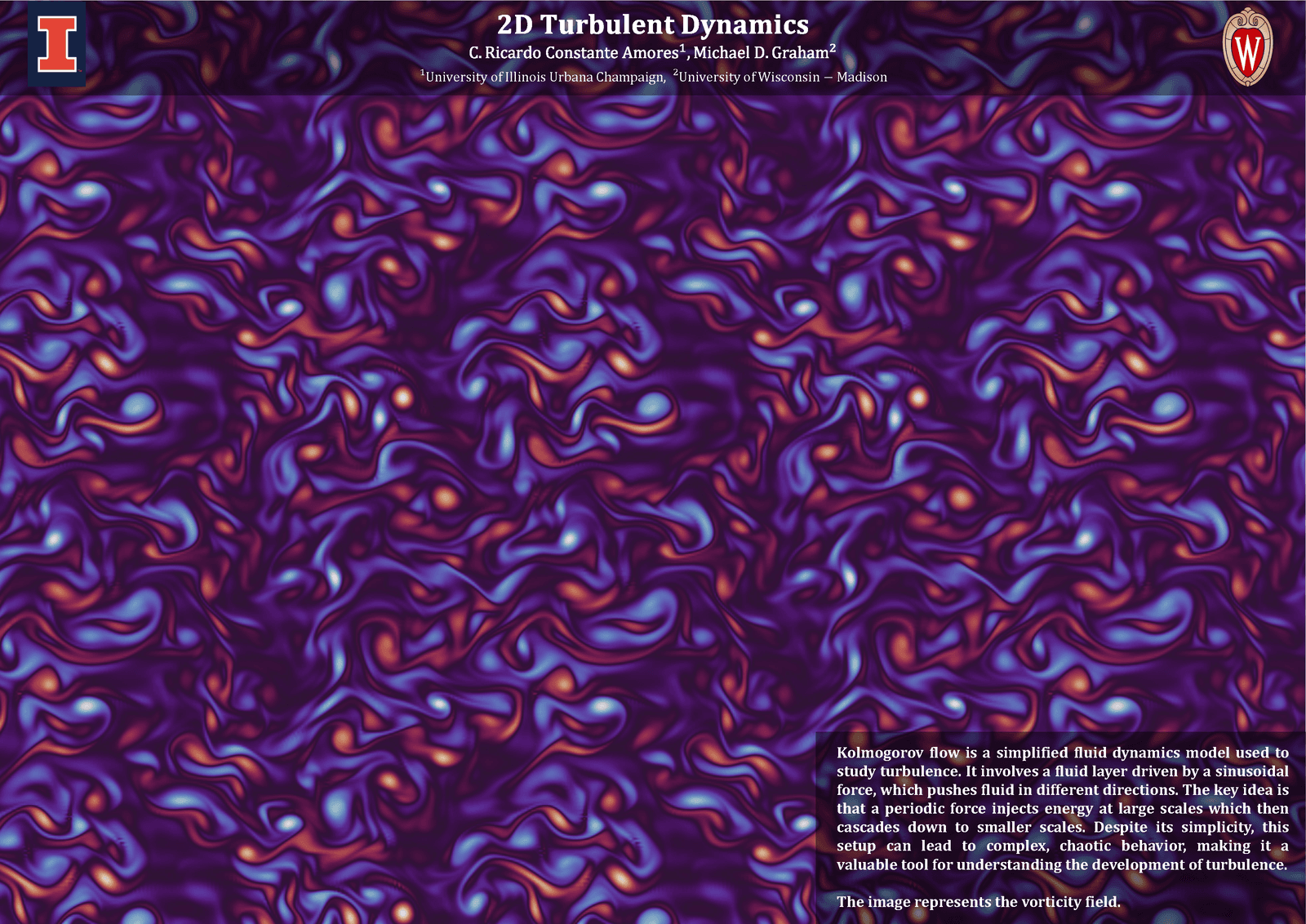

Kolmogorov Turbulence

Turbulent flows are ubiquitous, but they’re also mindbogglingly complex: ever-changing in both time and space across length scales both large and small. To try to unravel this complexity, scientists use simplified model problems. One such simplification is Kolmogorov flow: an imaginary flow where the fluid is forced back and forth sinusoidally. This large-scale forcing puts energy into the flow that cascades down to smaller length scales through the turbulent energy cascade. Here, researchers depict a numerical simulation of a turbulent Kolmogorov flow. The colors represent the flow’s vorticity field. Notice how your eye can pick out both tiny eddies and larger clusters in the flow; those patterns reflect the multi-scale nature of turbulence. (Image credit: C. Amores and M. Graham)

Bubbly Tornadoes Aspin

Rotating flows are full of delightful surprises. Here, the folks at the UCLA SpinLab demonstrate the power a little buoyancy has to liven up a flow. Their backdrop is a spinning tank of water; it’s been spinning long enough that it’s in what’s known as solid body rotation, meaning that the water in the tank moves as if it’s one big spinning object. To demonstrate this, they drop some plastic tracers into the water. These just drop to the floor of the tank without fluttering, showing that there’s no swirling going on in the tank. Then they add Alka-Seltzer tablets.

As the tablets dissolve, they release a stream of bubbles, which, thank to buoyancy, rise. As the bubbles rise, they drag the surrounding water with them. That motion, in turn, pulls water in from the surroundings to replace what’s moving upward. That incoming water has trace amounts of vorticity (largely due to the influence of friction near the tank’s bottom). As that vorticity moves inward, it speeds up to conserve angular momentum. This is, as the video notes, the same as a figure skater’s spin speeding up when she pulls in her arms. The result: a beautiful, spiraling bubble-filled vortex. (Video and image credit: UCLA SpinLab)

Visualizing Unstable Flames

Inside a combustion chamber, temperature fluctuations can cause sound waves that also disrupt the flow, in turn. This is called a thermoacoustic instability. In this video, researchers explore this process by watching how flames move down a tube. The flame fronts begin in an even curve that flattens out and then develops waves like those on a vibrating pool. Those waves grow bigger and bigger until the flame goes completely turbulent. Visually, it’s mesmerizing. Mathematically, it’s a lovely example of parametric resonance, where the flame’s instability is fed by system’s natural harmonics. (Video and image credit: J. Delfin et al.; research credit: J. Delfin et al. 1, 2)

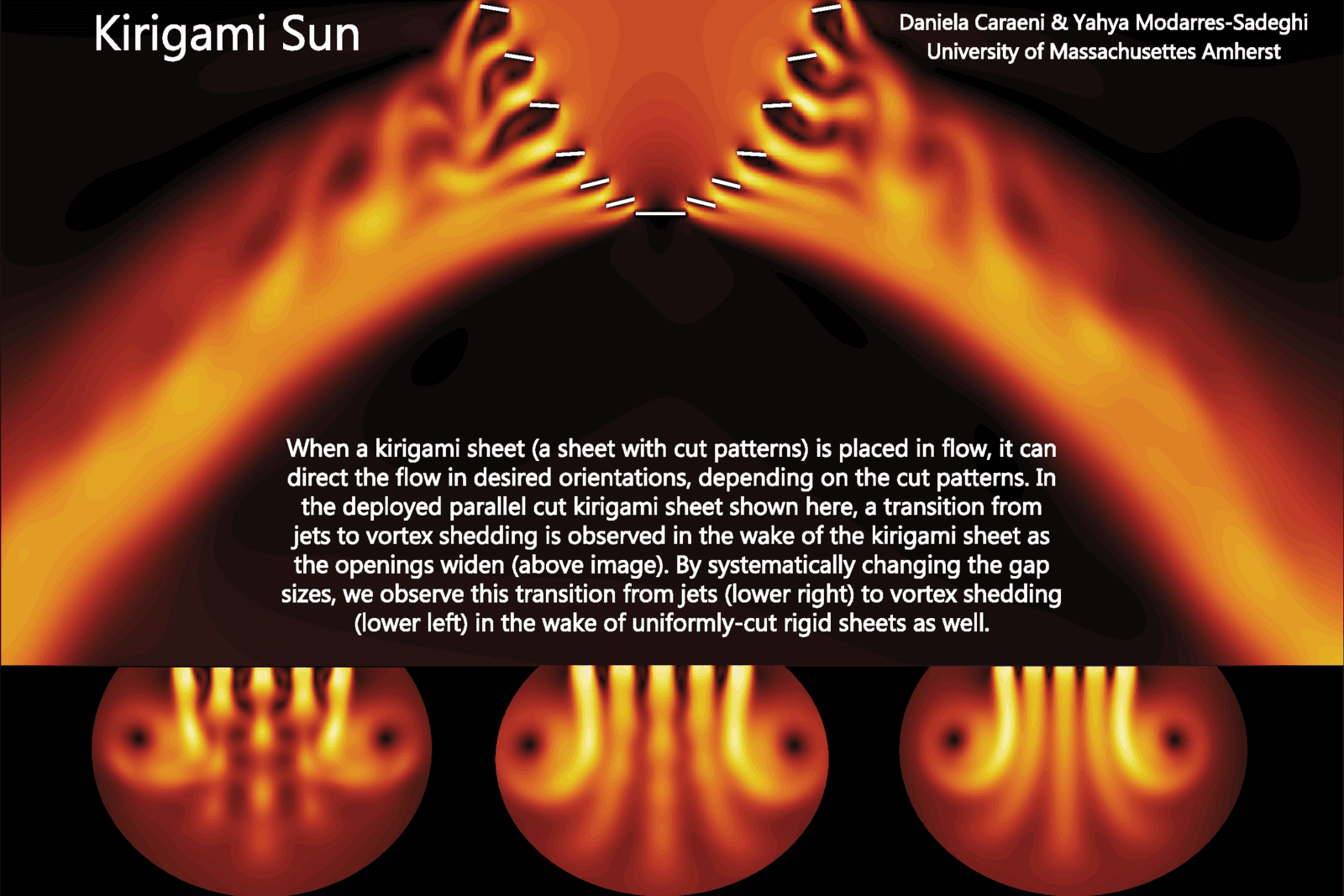

“Kirigami Sun”

Kirigami is a variation of origami in which paper can be cut as well as folded. Here, researchers look at flow through a cut kirigami sheet and how that flow changes with the cuts’ length. In the top central image, white lines mark the paper boundaries. As the cut gaps get larger, flow through them transitions from a continuous jet to swirling vortex shedding. Along the bottom, we see similar patterns emerge in the wake of uniformly-cut sheets, too. On the right, the flow comes through in jets; moving leftward, it transitions to an unsteady vortex shedding flow. (Image credit: D. Caraeni and Y. Modarres-Sadeghi)