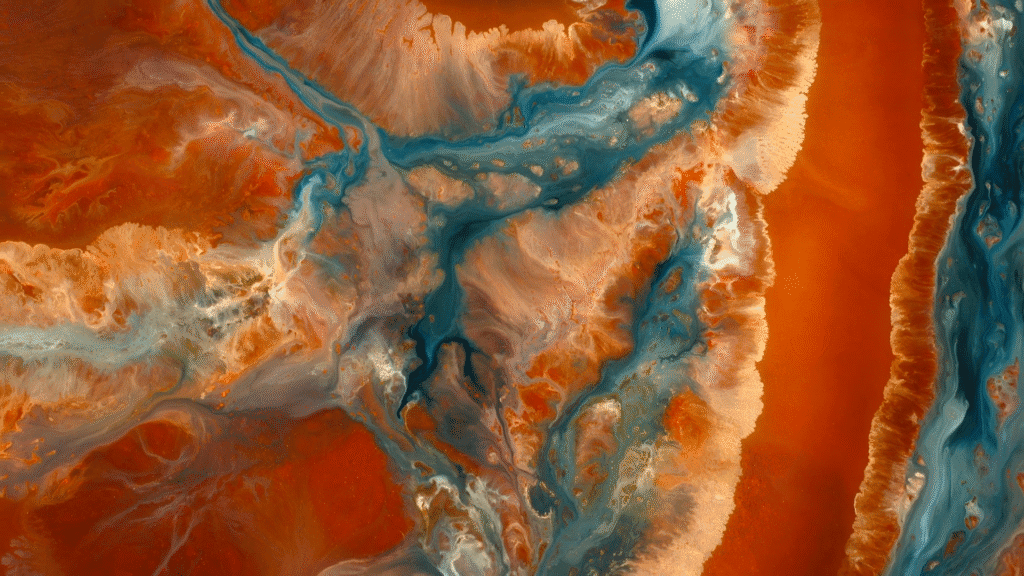

On the heels of his behind-the-scenes introduction, here’s the first volume of artist Roman De Giuli’s “Now I See”. In it, we appear to soar above vast colorful landscapes. Rivers flow past islands. Glaciers creep along valleys. Canyons cut through deserts. It’s like a bird’s eye view of our planet’s terrestrial wonders. (Video and image credit: R. De Giuli)

Tag: flow visualization

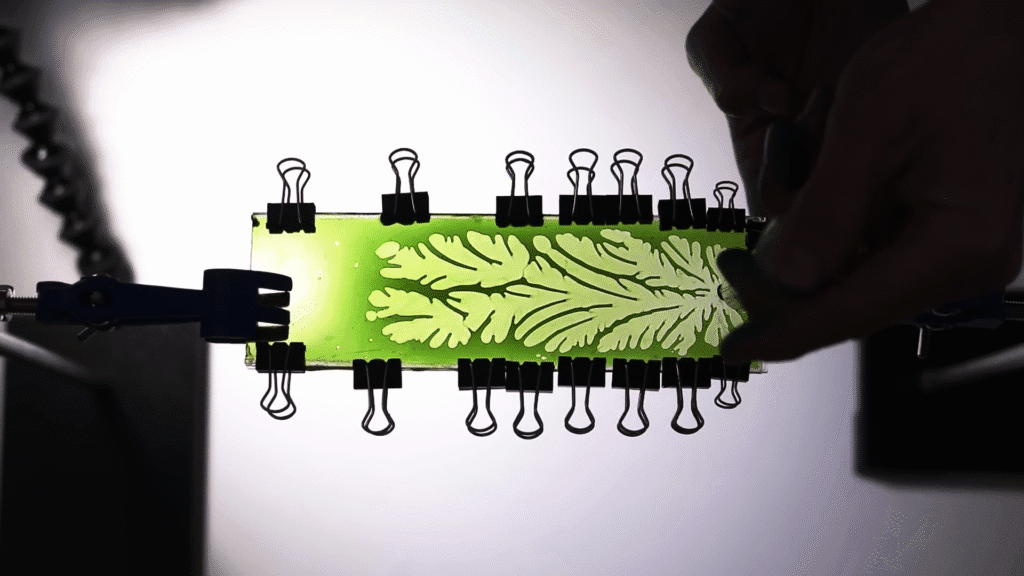

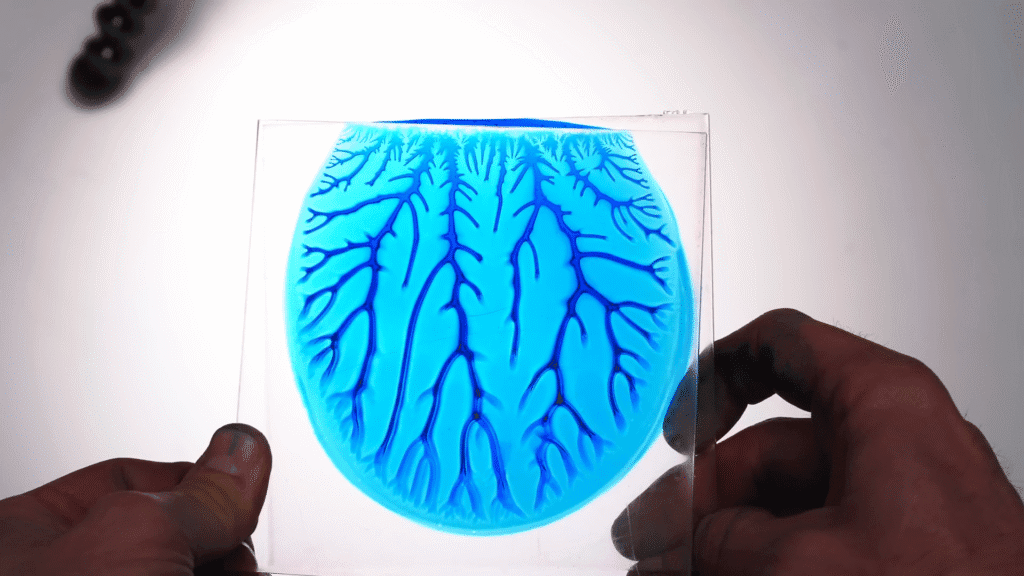

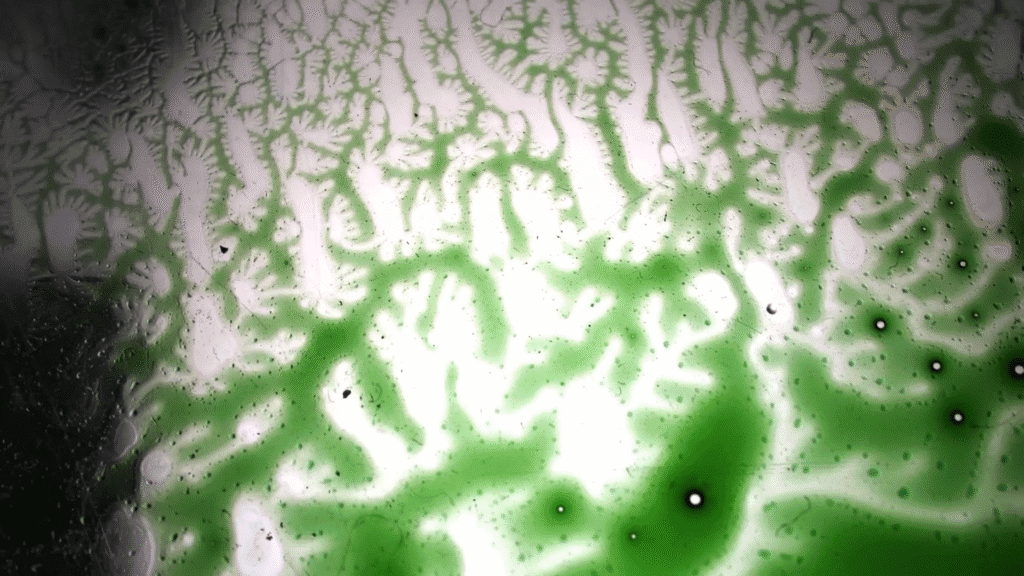

Fractal Fingers

As bizarre as the branching fractal fingers of the Saffman-Taylor instability look, they’re quite a common phenomenon. In his video, Steve Mould demonstrates how to make them by sandwiching a viscous liquid like school glue between two acrylic sheets and then pulling them apart. The more formal lab-version of this is the Hele-Shaw cell, which he also demonstrates. But you may have come across the effect when pealing up a screen protector or in dealing with a cracked phone screen. In all of these cases, a less viscous fluid — specifically air — is forcing its way into a more viscous fluid, something that it cannot manage without the fluid interface fracturing. (Video and image credit: S. Mould)

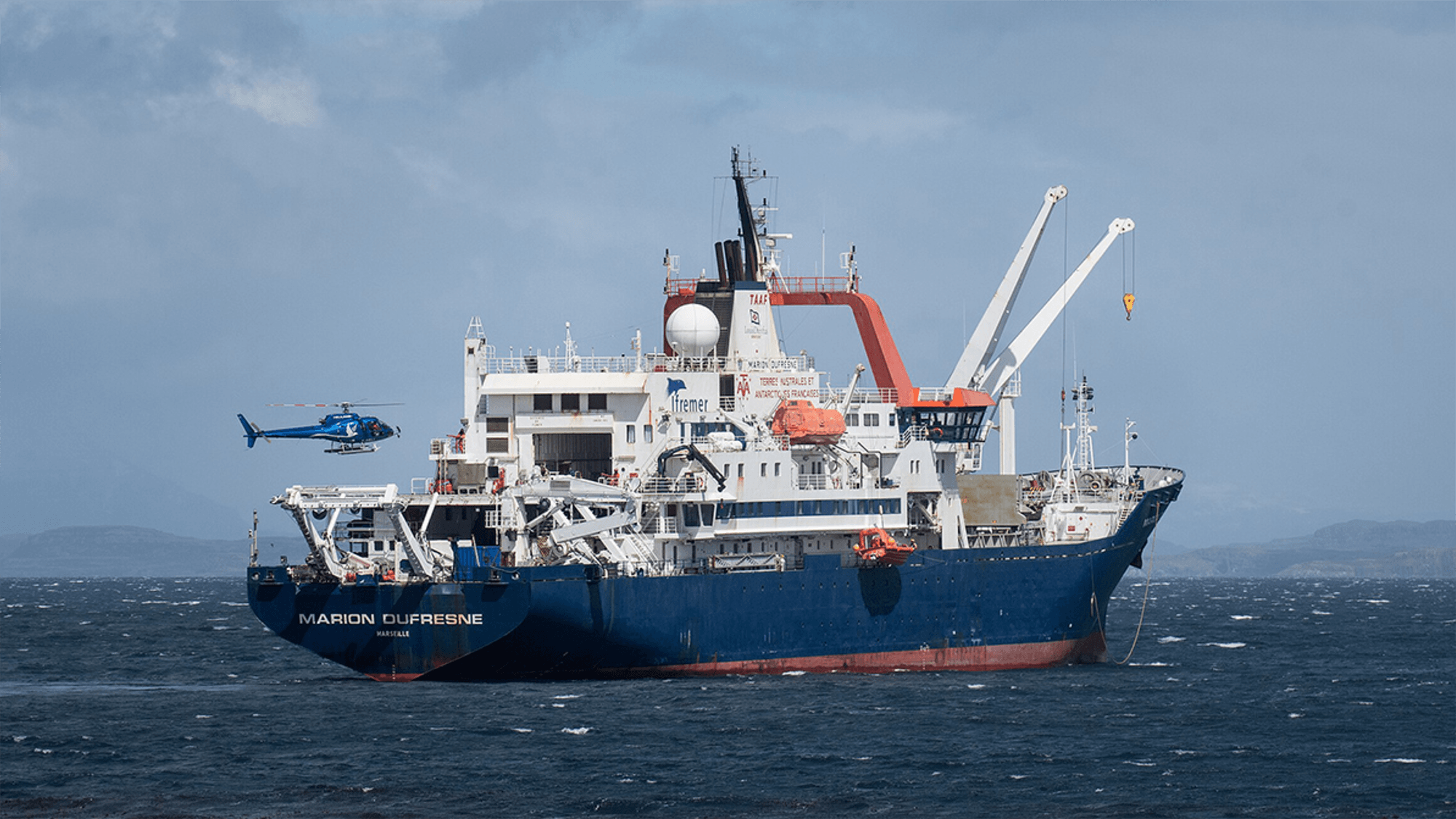

Mapping the Mozambique Channel

The Mozambique Channel boasts some of the world’s most turbulent waters, driven by eddies hundreds of kilometers wide. Eddies of this size — known as mesoscale — determine regional flows that influence local biodiversity, sediment mixing, and how plastic pollution moves. To better understand the region, scientists measured a mesoscale dipole from a research vessel.

Illustration of flows in the Mozambique Channel. The anticyclonic ring in dark blue rotates counterclockwise and consists of largely uniform water (labeled Ring: R1). To the south, in green, a cyclonic eddy rotates in a clockwise sense (labeled Cyclone: C1). This area is chlorophyll-rich and has varying salinity levels. Between the two is a filament of chlorophyll-rich water being drawn from the near-shore region (labeled Filament: F1). The dipole consisted of a large anticyclonic ring (shown in dark blue) that rotated counterclockwise and a smaller cyclonic eddy (shown in green) that rotated clockwise. Between these eddies lay a central jet moving up to 130 centimeters per second that drew material out from the shoreline. In the anticyclonic ring, researchers found largely uniform waters with little chlorophyll. The cyclonic eddy, in contrast, was high in chlorophyll and had large variations in salinity. Those smaller-scale variations, they found, helped to drive vertical motions of up to 40 meters per day.

In situ measurements like these help scientists understand how energy flows through different scales in the ocean and how that energy helps transport nutrients, sediment, and pollution regionally. Such measurements also help us to refine ocean models that enable us to predict this transport and how regions will change as climate patterns shift. (Image credit: ship – A. Lamielle/Wikimedia Commons, eddies – P. Penven et al.; research credit: P. Penven et al.; via Eos)

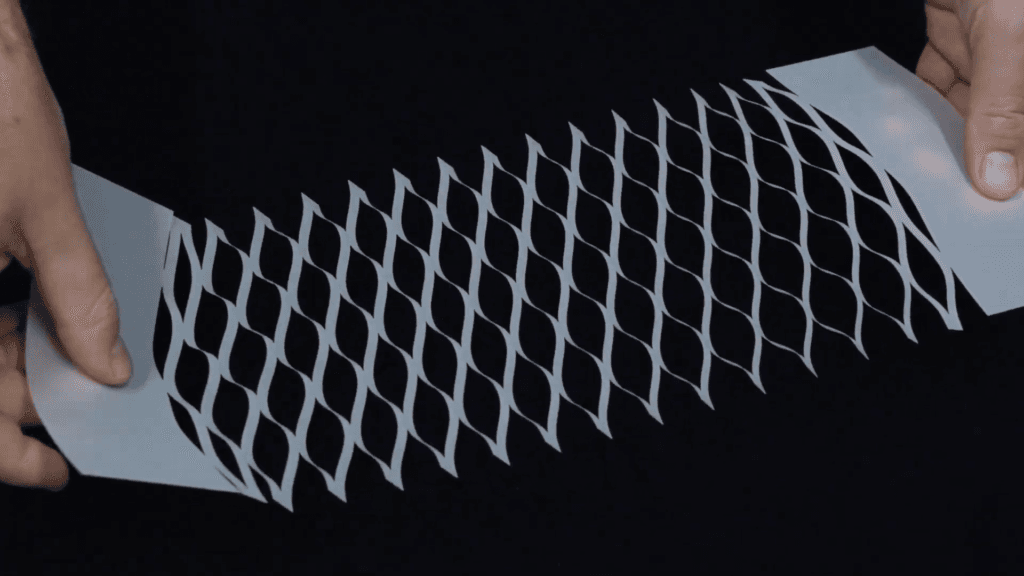

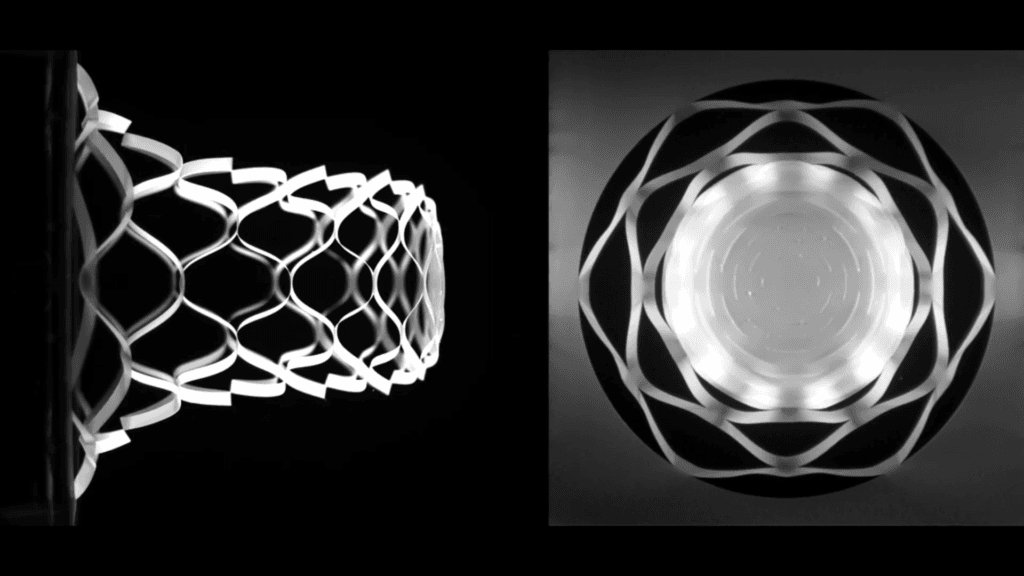

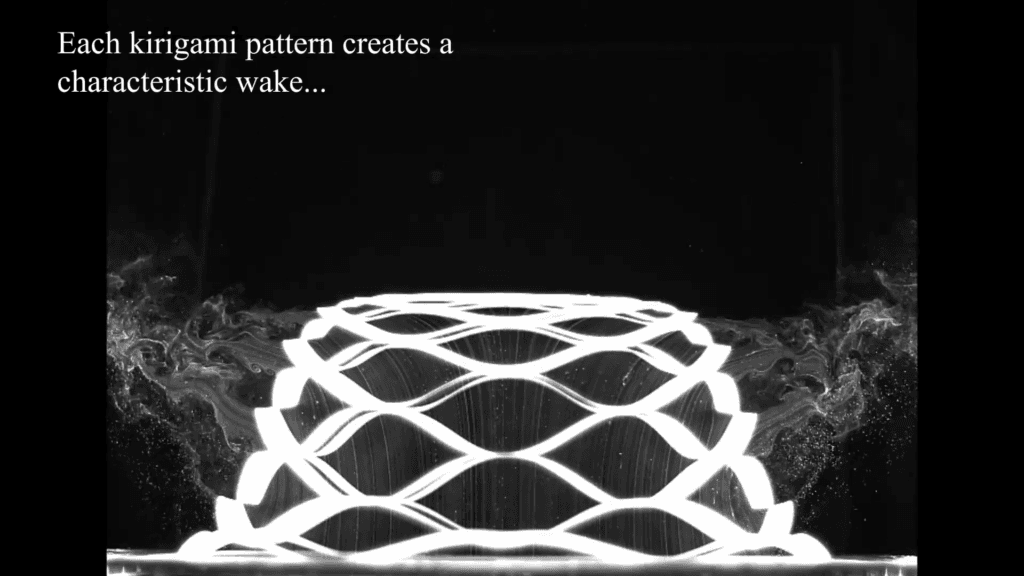

Kirigami in the Flow

Kirigami is a paper art that combines folding and cutting to create elaborate shapes. Here, researchers use cuts in thin sheets of plastic and explore how the sheets transform in a flow. Depending on the configuration of cuts, the sheets can stretch dramatically in the flow, creating complex, dynamic, and beautiful wakes. I feel like there must be some applications out there that would benefit from kirigami-induced mixing. (Video and image credit: A. Carleton and Y. Modarres-Sadeghi)

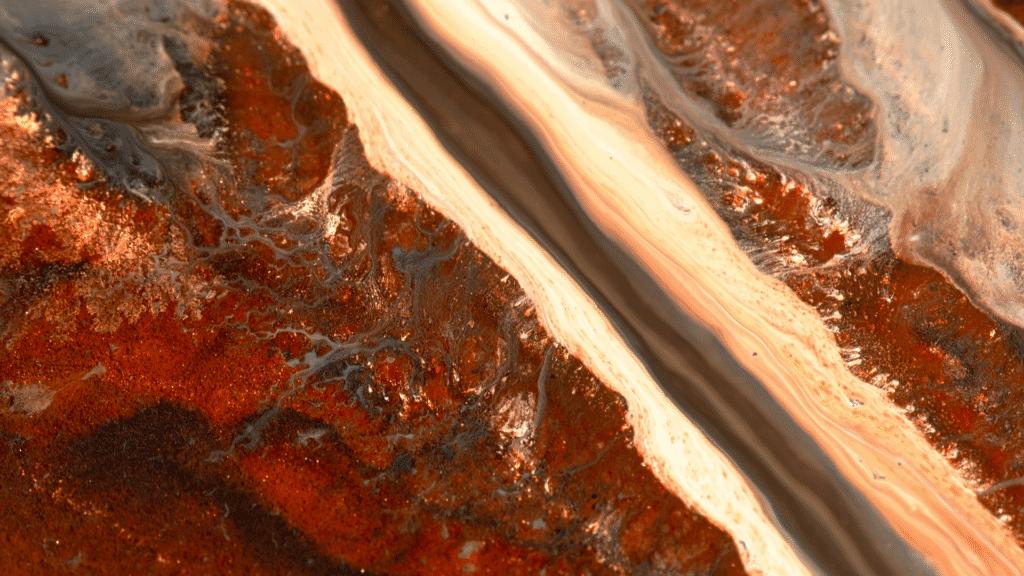

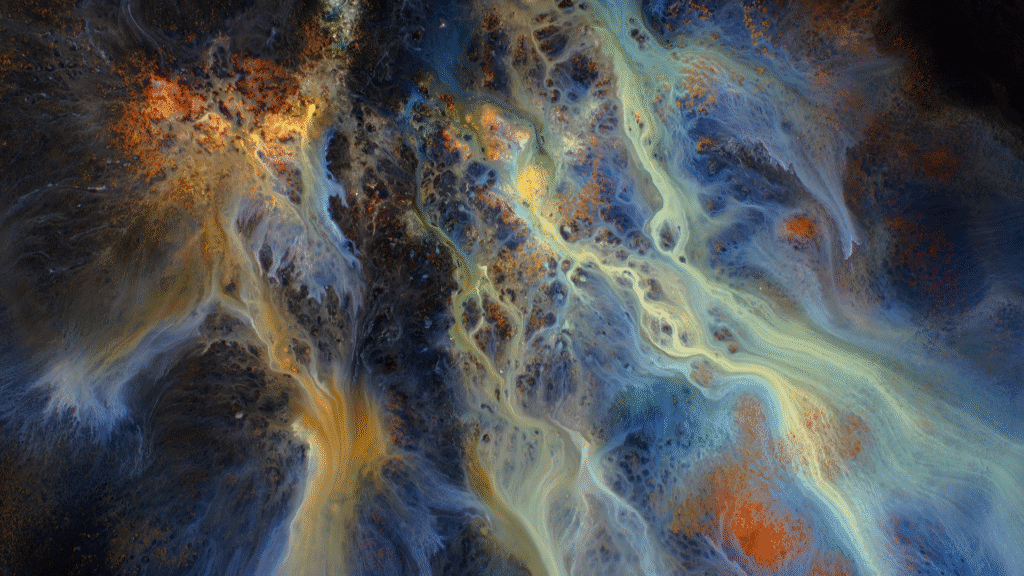

Creating Liquid Landscapes

Artist Roman De Giuli excels at creating what appear to be vast landscapes carved by moving water. In reality, these pieces are small-scale flows, created on paper. Now, De Giuli takes us behind the scenes to see how he creates these masterpieces — layering, washing, burning, and repeating to build up the paperscape that eventually hosts the flows we see recorded. The work is meticulous and slow, and the results are incredible. De Giuli’s videos never fail to transport me to a calmer, more pristine version of our world. I can’t wait to see the new series! (Video and image credit: R. De Giuli)

Escape From Yavin 4

In an ongoing tradition, let’s take another look at some Star Wars-inspired aerodynamics. This year it’s the TIE fighter’s turn. Here, researchers simulate the spacecraft trying to escape Yavin 4’s atmosphere at Mach 1.15. The research poster’s blue contours show pressure contours, with darker colors connoting higher pressures. The bright low pressure region immediately behind the craft suggests a difficult, high-drag ascent and a turbulent, subsonic wake despite the craft’s supersonic velocity. (Image credit: A. Martinez-Sanchez et al.)

Quietening Drones

A drone’s noisiness is one of its major downfalls. Standard drones are obnoxiously loud and disruptive for both humans and animals, one reason that they’re not allowed in many places. This flow visualization, courtesy of the Slow Mo Guys, helps show why. The image above shows a standard off-the-shelf drone rotor. As each blade passes through the smoke, it sheds a wingtip vortex. (Note that these vortices are constantly coming off the blade, but we only see them where they intersect with the smoke.) As the blades go by, a constant stream of regularly-spaced vortices marches downstream of the rotor. This regular spacing creates the dominant acoustic frequency that we hear from the drone.

Animation of wingtip vortices coming off a drone rotor with blades of different lengths. This causes interactions between the vortices, which helps disrupt the drone’s noise. To counter that, the company Wing uses a rotor with blades of different lengths (bottom image). This staggers the location of the shed vortices and causes some later vortices to spin up with their downstream neighbor. These interactions break up that regular spacing that generates the drone’s dominant acoustic frequency. Overall, that makes the drone sound quieter, likely without a large impact to the amount of lift it creates. (Image credit: The Slow Mo Guys)

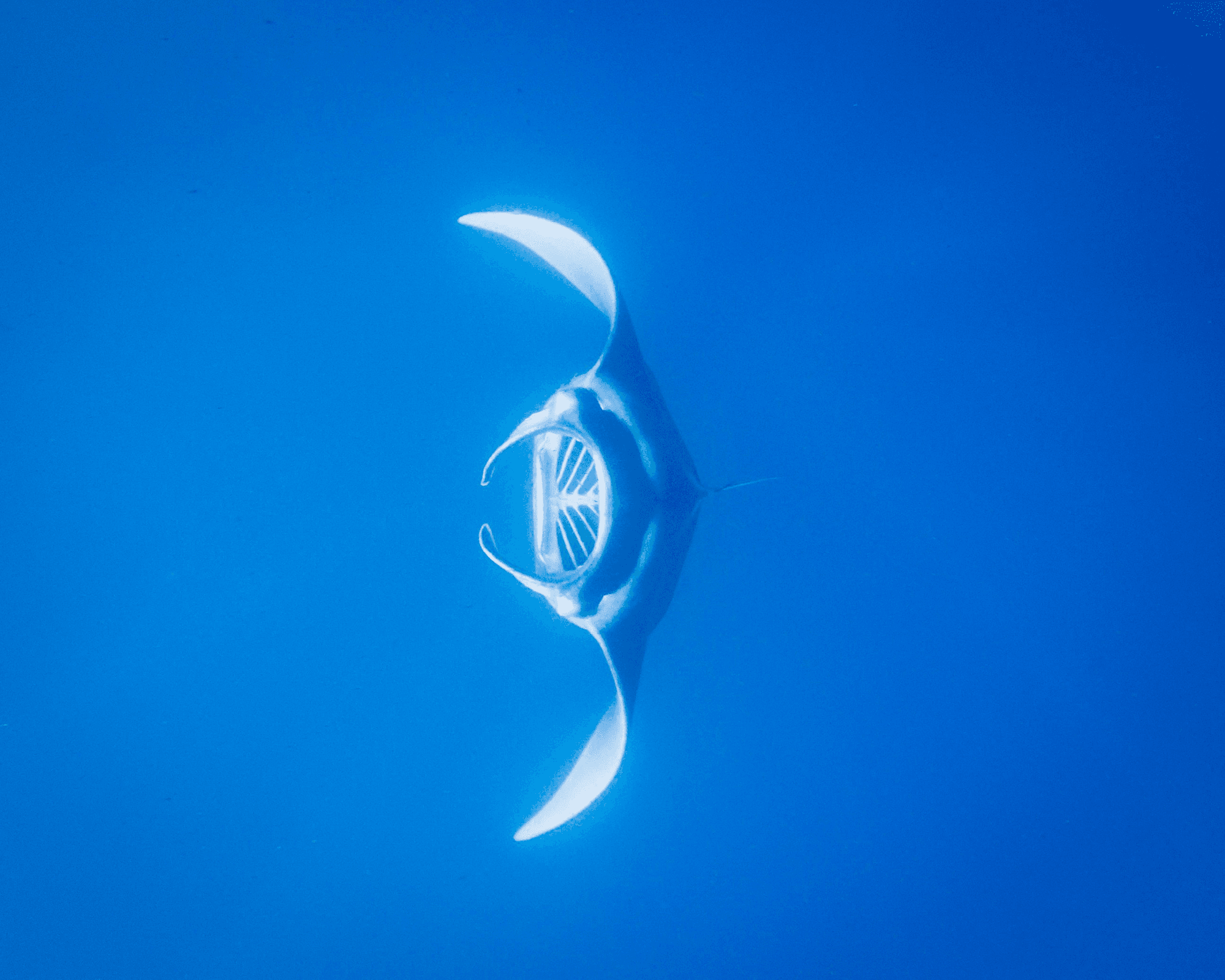

Filtering Like a Manta Ray

As manta rays swim, they’re constantly doing two important — but not necessarily compatible — things: getting oxygen to breathe and collecting plankton to eat. That requires some expert filtering to send food particles toward their stomach and oxygen-rich water to their gills. Manta rays do this with a built-in filter that resembles an industrial crossflow filter. Researchers built a filter inspired by a manta ray’s geometry, and found that it has three different flow states, based on the flow speed. At low speeds, flow moves freely down the filter’s channels; in a manta, this would carry both water and particles toward the gills. At medium speeds, vortices start to form at the entrance to the filter channels. This sends large particles downstream (toward a manta’s digestive system) while water passes down the channels. At even greater speeds, each channel entrance develops a vortex. That allows water to pass down the filter channels but keeps particles out. (Image credit: manta – N. Weldingh, filter – X. Mao et al.; research credit: X. Mao et al.; via Ars Technica)

Depending on the flow speed, a manta-inspired filter can allow both water and particles in or filter particles out of the water.

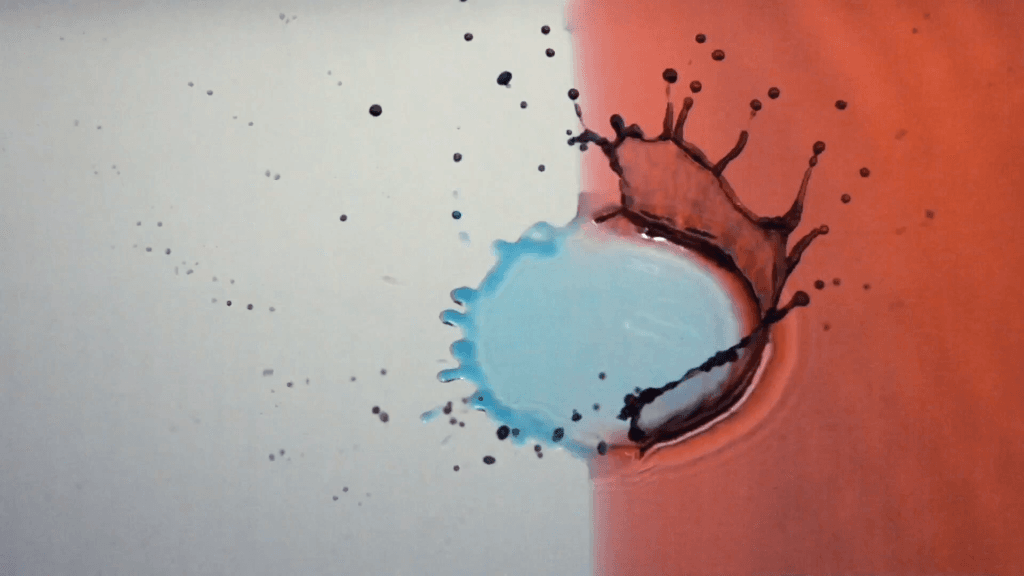

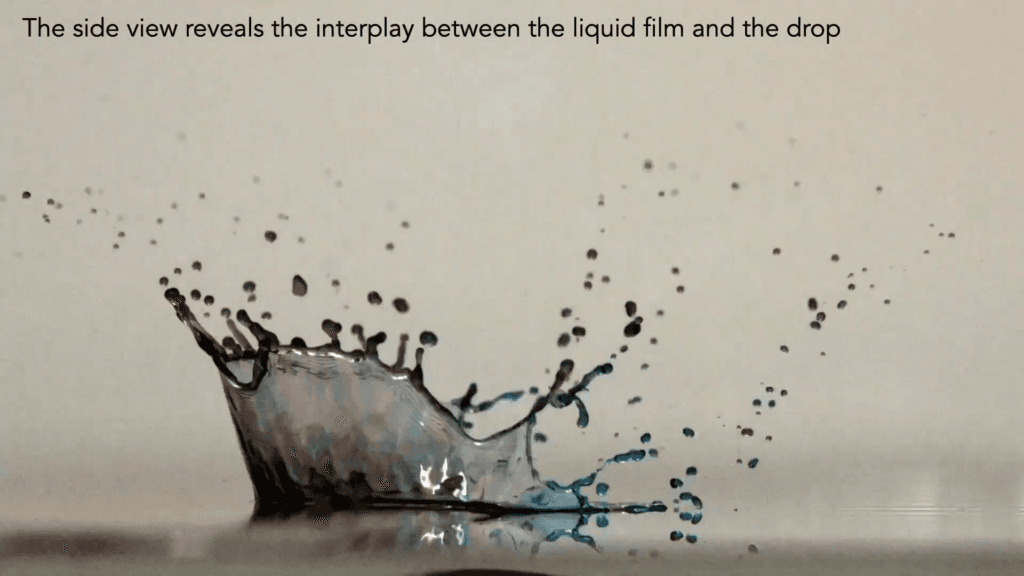

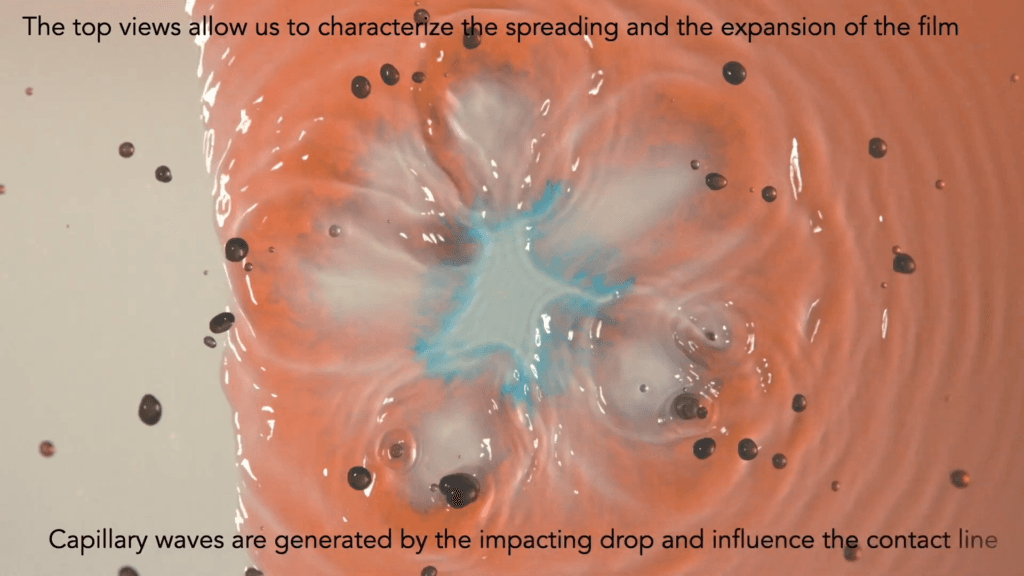

Drops on the Edge

Drops impacting a dry hydrophilic surface flatten into a film. Drops that impact a wet film throw up a crown-shaped splash. But what happens when a drop hits the edge of a wet surface? That’s the situation explored in this video, where blue-dyed drops interact with a red-dyed film. From every angle, the impact is complex — sending up partial crown splashes, generating capillary waves that shift the contact line, and chaotically mixing the drop and film’s liquids. (Video and image credit: A. Sauret et al.)

Salt Fingers

Any time a fluid under gravity has areas of differing density, it convects. We’re used to thinking of this in terms of temperature — “hot air rises” — but temperature isn’t the only source of convection. Differences in concentration — like salinity in water — cause convection, too. This video shows a special, more complex case: what happens when there are two sources of density gradient, each of which diffuses at a different rate.

The classic example of this occurs in the ocean, where colder fresher water meets warmer, saltier water (and vice versa). Cold water tends to sink. So does saltier water. But since temperature and salinity move at different speeds, their competing convection takes on a shape that resembles dancing, finger-like plumes as seen here. (Video and image credit: M. Mohaghar et al.)