Espresso has some pretty cool physics. But it’s also just lovely to watch in slow motion. This video offers a look at the making of an espresso shot at 120 frames per second (though you can also enjoy a 1000 fps version here). Watching the film form, expand, and break up at the beginning and end of the video is my favorite, but watching how the occasional solid coffee grains make their way into and down the central jet is really interesting also. (Video and image credit: YouTube/skunkay; via Open Culture)

Tag: flow visualization

How Particles Affect Melting Ice

When ice melts in salt water, there’s an upward flow along the ice caused by the difference in density. But most ice in nature is not purely water. What happens when there are particles trapped in the ice? That’s the question this video asks. The answer turns out to be relatively complex, but the researchers do a nice job of stepping viewers through their logic.

Large particles tend to fall off one-by-one, which doesn’t really affect the buoyant upward flow along the ice. In contrast, smaller particles fall downward in a plume that completely overwhelms the buoyant flow. That strong downward flow makes the ice ablate even faster. (Video and image credit: S. Bootsma et al.)

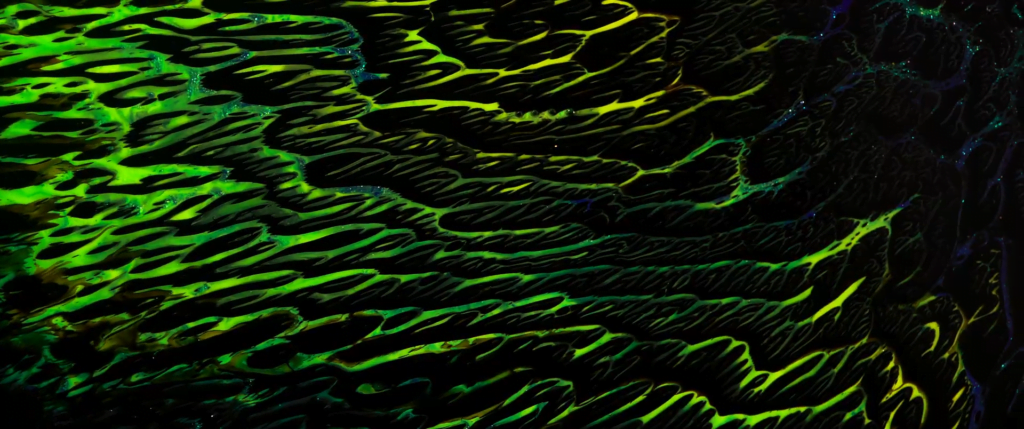

Baltic Bloom

June and July brings blooming phytoplankton to the Baltic Sea, seen here in late July 2025. On-the-water measurements show that much of this bloom was cyanobacteria, an ancient type of organism among the first to process carbon dioxide into oxygen. These organisms thrive in nutrient- and nitrogen-rich waters. Here, they mark out the tides and currents that mix the Baltic. Zoom in on the full image, and you’ll see dark, nearly-straight lines across the swirls; these are the wakes of boats. (Image credit: M. Garrison; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Salty Swirls

Flamingos soar over swirls of salt and algae in a lake in Kenya’s Rift Valley. Shaped by winds, currents, physics, and chemistry these eddies reflect the motion of the water, evaporation patterns, and more. Without more information, it’s hard to say exactly what shapes the pattern, but it does appear reminiscent of a Kelvin-Helmholtz instability in places. (Image credit: B. Hayden/IAPOTY; via Colossal)

Glacier Timelines

Over the past 150 years, Switzerland’s glaciers have retreated up the alpine slopes, eaten away by warming temperatures induced by industrialization. But such changes can be difficult for people to visualize, so artist Fabian Oefner set out to make these changes more comprehensible. These photographs — showing the Rhone and Trift glaciers — are the result. Oefner took the glacial extent records dating back into the 1800s and programmed them into a drone. Lit by LED, the drone flew each year’s profile over the mountainside, with Oefner capturing the path through long-exposure photography. When all the paths are combined, viewers can see the glacier’s history written on its very slopes. The effect is, fittingly, ghost-like. We see a glimpse of the glacier as it was, laid over its current remains. (Image credit: F. Oefner; video credit: Google Arts and Culture)

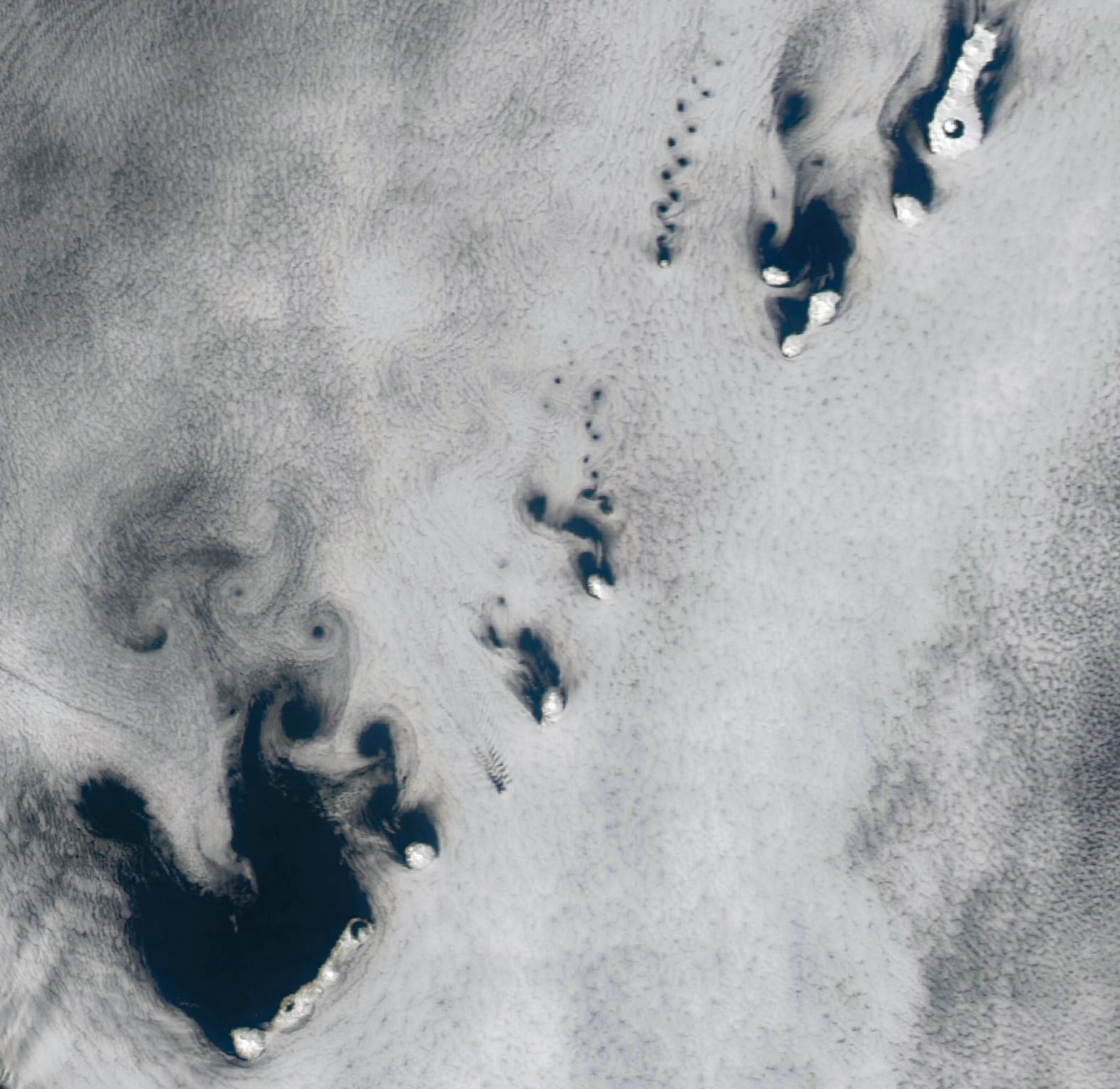

A Variety of Vortices

Winds parted around the Kuril Islands and left behind a string of vortices in this satellite image from April 2025. This pattern of alternating vortices is known as a von Karman vortex street. The varying directions of the vortex streets show that winds across the islands ranged from southeasterly to southerly. Notice also that the size of the island dictates the size of the vortices. Larger islands create larger vortices, and smaller islands have smaller and more frequent vortices. (Image credit: M. Garrison; via NASA Earth Observatory)

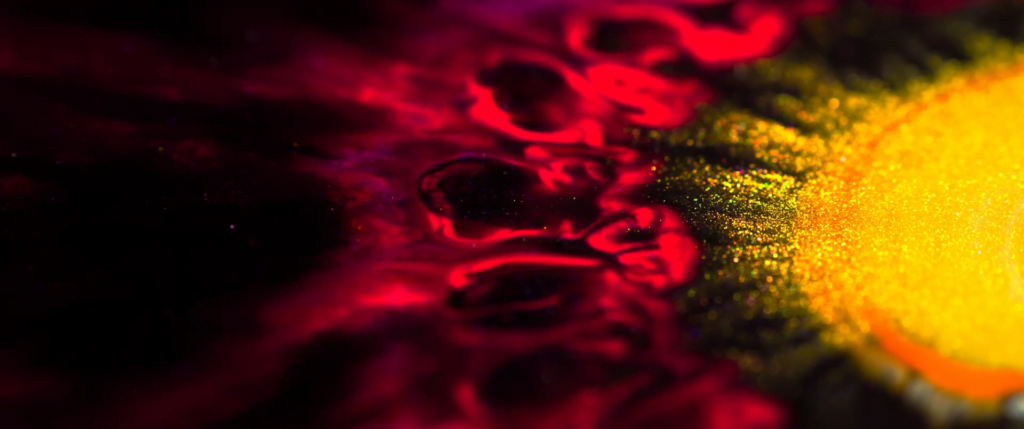

“Creation”

Videographer Vadim Sherbakov’s short film “Creation” is full of glittery vistas created under a macro lens. Shifting, particle-seeded flows shimmer in bright colors. Glistening deltas shift and form, and Marangoni flows generate feathers and tree-like dendritic arms. Macro flows never cease to fascinate. (Video and image credit: V. Sherbakov; via Colossal)

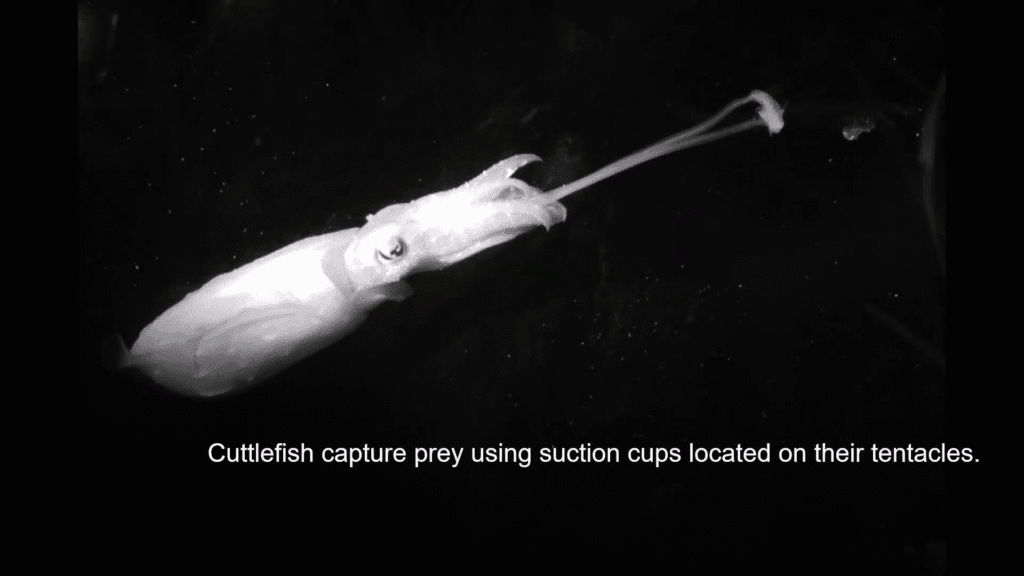

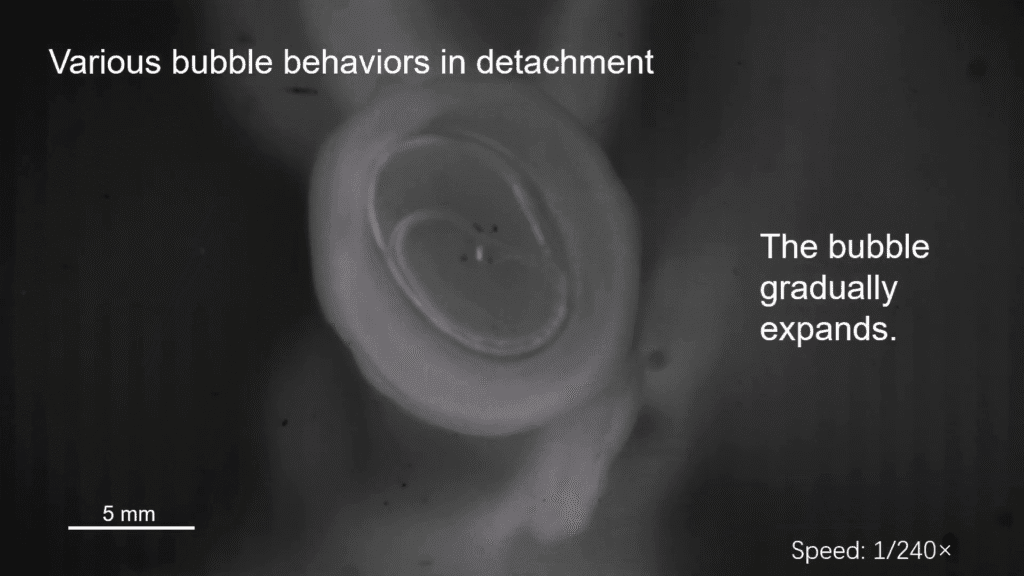

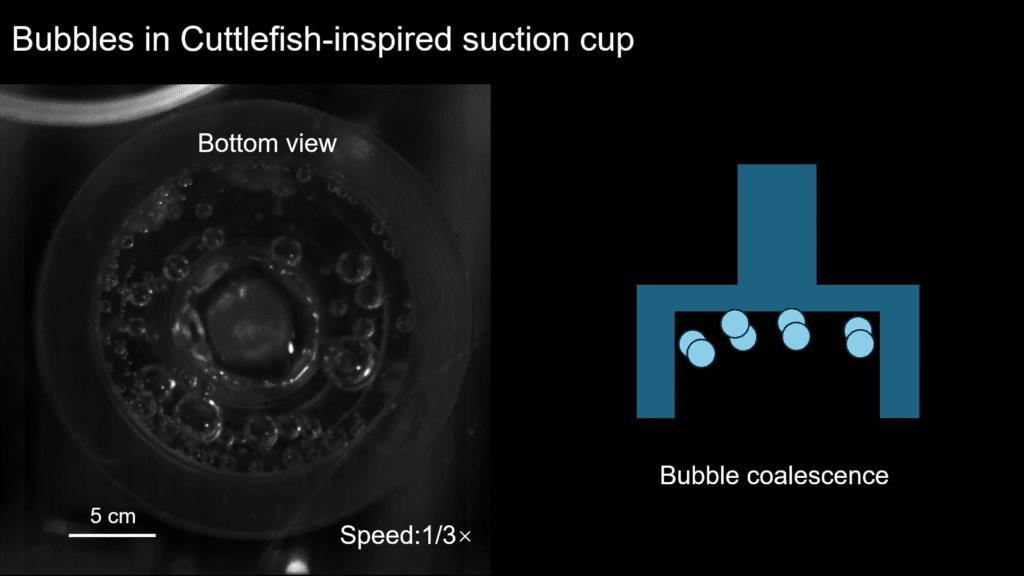

Inside Cuttlefish Suction

Cuttlefish, like many cephalopods, catch prey with their tentacles. Suction cups along the tentacle help them hold on. In this video, researchers share preliminary studies of what goes on inside these suction cups as they’re detached. The low pressures inside the suction cup cause water to vaporize, temporarily. As seen for both the cuttlefish and a bio-inspired suction cup, small bubbles form inside the attached cup, coalesce into larger bubbles, and then get destroyed in the catastrophic leak that occurs once part of the suction cup detaches. (Video and image credit: B. Zhang et al.)

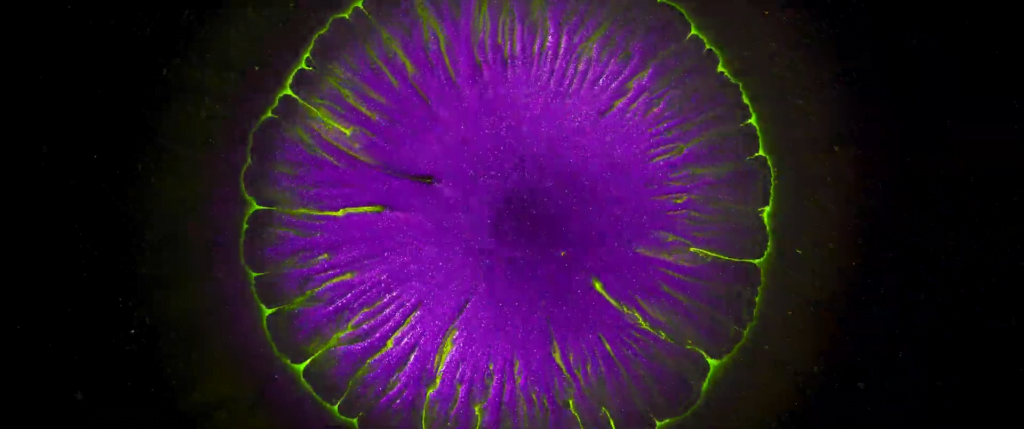

Glimpses of Coronal Rain

Despite its incredible heat, our sun‘s corona is so faint compared to the rest of the star that we can rarely make it out except during a total solar eclipse. But a new adaptive optic technique has given us coronal images with unprecedented detail.

These images come from the 1.6-meter Goode Solar Telescope at Big Bear Solar Observatory, and they required some 2,200 adjustments to the instrument’s mirror every second to counter atmospheric distortions that would otherwise blur the images. With the new technique, the team was able to sharpen their resolution from 1,000 kilometers all the way down to 63 kilometers, revealing heretofore unseen details of plasma from solar prominences dancing in the sun’s magnetic field and cooling plasma falling as coronal rain.

The team hope to upgrade the 4-meter Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope with the technology next, which will enable even finer imagery. (Image credit: Schmidt et al./NJIT/NSO/AURA/NSF; research credit: D. Schmidt et al.; via Gizmodo)

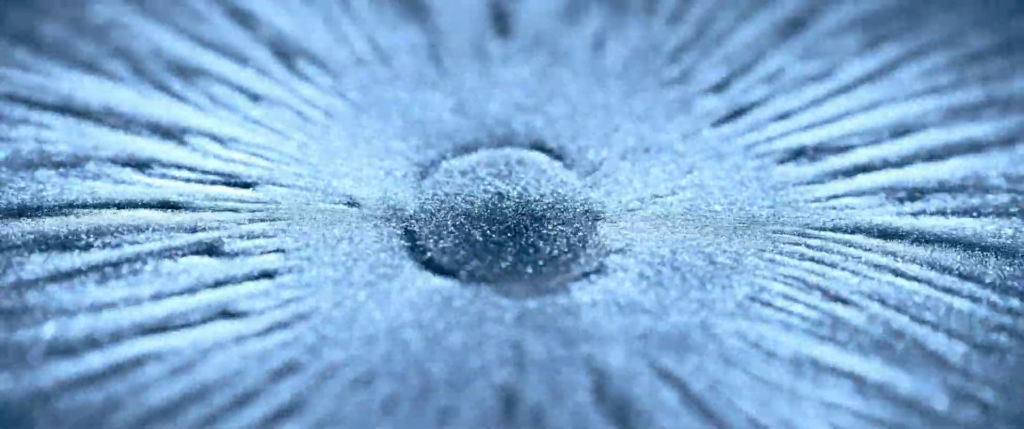

Bow Shock Instability

There are few flows more violent than planetary re-entry. Crossing a shock wave is always violent; it forces a sudden jump in density, temperature, and pressure. But at re-entry speeds this shock wave is so strong the density can jump by a factor of 13 or more, and the temperature increase is high enough that it literally rips air molecules apart into plasma.

Here, researchers show a numerical simulation of flow around a space capsule moving at Mach 28. The transition through the capsule’s bow shock is so violent that within a few milliseconds, all of the flow behind the shock wave is turbulent. Because turbulence is so good at mixing, this carries hot plasma closer to the capsule’s surface, causing the high temperatures visible in reds and yellows in the image. Also shown — in shades of gray — is the vorticity magnitude of flow around the capsule. (Image credit: A. Álvarez and A. Lozano-Duran)