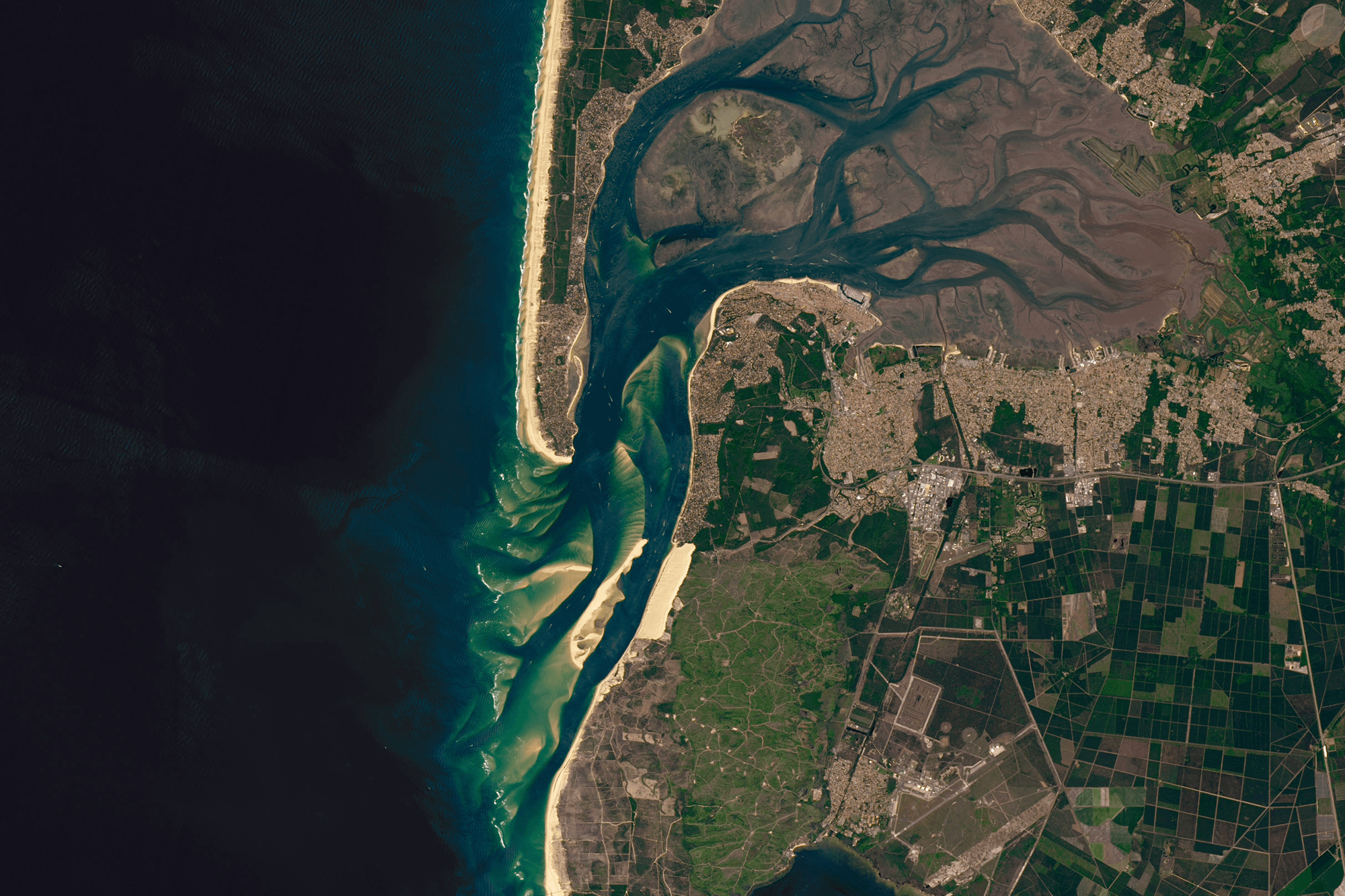

Taken from a Cessna aircraft, photographer J. Fritz Rumpf’s image of a Brazilian landscape appears abstract. But it captures a serpentine river and surrounding dunes, dyed brown by decaying plant matter and sculpted by the forces of wind and current. This shot is part of a portfolio that won him the title of 2025 International Landscape Photographer of the Year. (Image credit: J. Rumpf; via ILPOTY)

Tag: dunes

La Grande Dune du Pilat

Southwest of Bordeaux in France stands Europe’s tallest sand dune, La Grande Dune du Pilat. Some 2.7 kilometers long and over 100 meters high, this dune took shape here over thousands of years. It moves inland a few meters every year as winds blowing from the Atlantic push sand up its shallow seaward side to the dune’s crest. There, sand will avalanche down the steeper leeward side, advancing the dune little by little. The dune’s accumulation has not been steady; during cooler and drier times, sand has collected there, but it took warmer and wetter climes to grow the forests that have helped stabilize the soil and build the dune higher. Humanity has played a role as well, at times introducing new tree species to stabilize the dune. (Image credit: W. Liang; via NASA Earth Observatory)

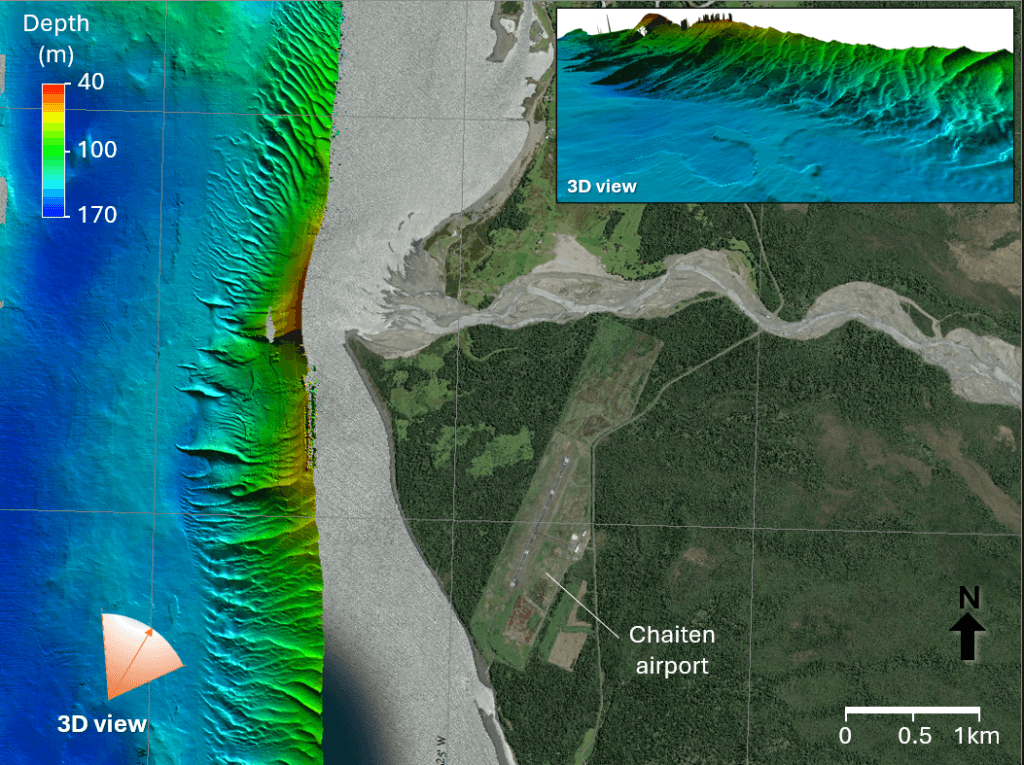

The Underwater Effects of Volcanoes

Although volcanoes are typically located in or near the ocean, we’ve spent relatively little effort studying how eruptions affect the marine environment. A recent research voyage aimed to change that by studying the Patagonian Sea near the site of the 2008 Chaitén eruption. Marked by massive ashfalls that, when mixed with heavy rains, created huge mudslides, the 2008 eruption was the Chaitén volcano’s first in 9,000 years.

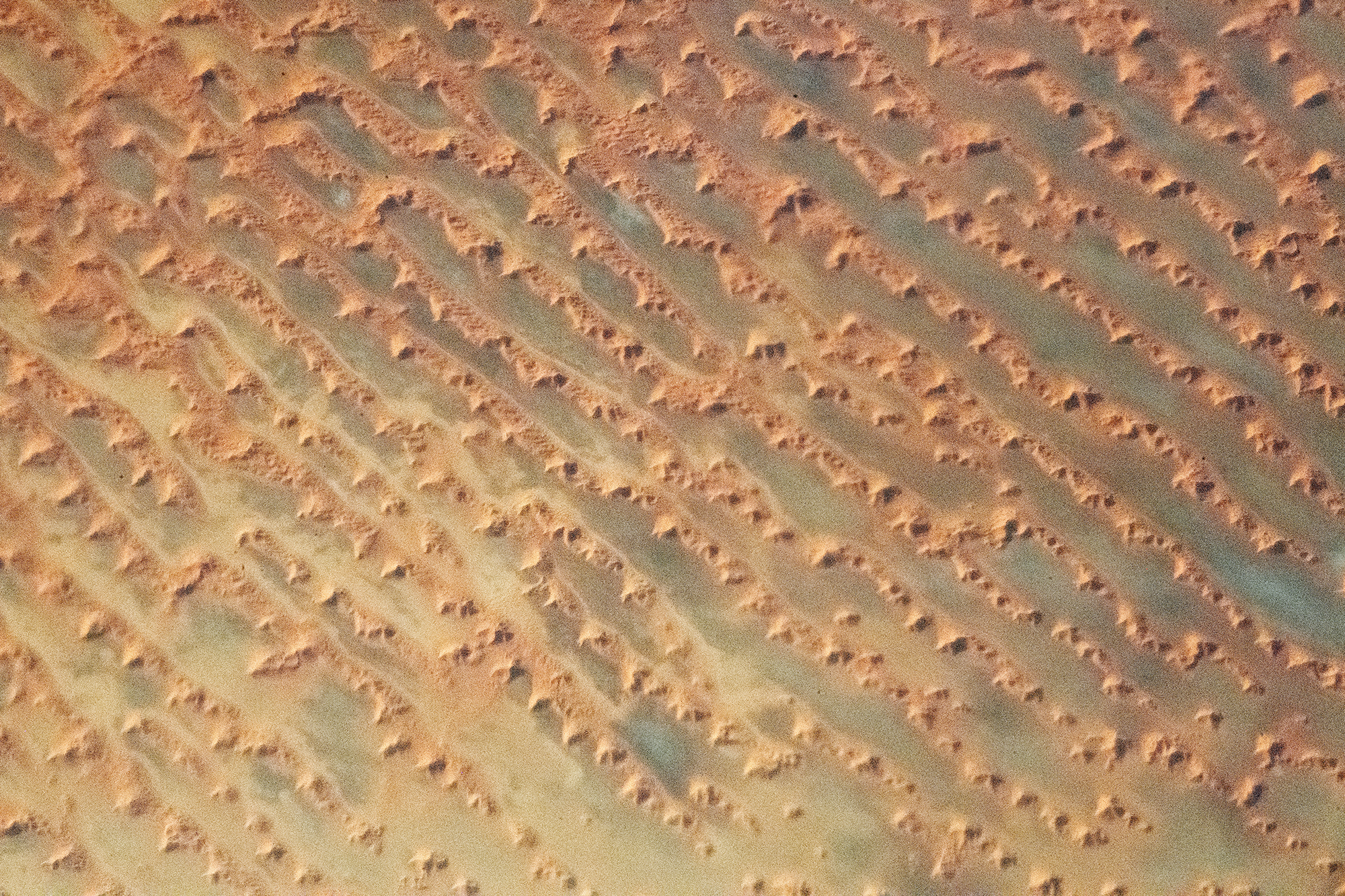

The researchers mapped the seafloor near the volcano, finding massive dunes shaped by strong currents. Using a remotely operated vehicle, the team surveyed and sampled the seafloor, collecting sediments reaching back some 15,000 years. They also located ash from the 2008 eruption over 24 kilometers from the volcano. With their data, they hope to understand both how the recent eruption changed the marine environment as well as how older eruptions affected the area. (Image credits: volcano – USGS, dunes – Schmidt Ocean Institute; see also Schmidt Ocean Institute; via Ars Technica)

Composite image showing the massive underwater dunes off the coast. P.S. – This Friday, January 24th from 12 to 1:30pm Eastern I’m moderating a panel discussion on the Traveling Gallery of Fluid Motion and how art and science can work together in public outreach. Register here to join. It’s free!

Junggar Basin Aglow

The low sun angle in this astronaut photo of Junggar Basin shows off the wind- and water-carved landscape. Located in northwestern China, this region is covered in dune fields, appearing along the top and bottom of the image. The uplifted area in the top half of the image is separated by sedimentary layers that lie above the reddish stripe in the center of the photo. Look closely in this middle area, and you’ll find the meandering banks of an ephemeral stream. Then the landscape transitions back into sandy wind-shaped dunes. (Image credit: NASA; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Complex Dunes

Sometimes landscapes have a beauty that’s hard to see from the ground. This astronaut’s photo shows a dune field in the sand seas of Saudi Arabia. Vast linear dunes line up along the direction of prevailing winds. Atop these dunes are more complex formations, star dunes, that are built up in the wake of changing winds. Built from three or more intersecting arms, the star dunes are steeper than the linear dunes they sit atop. Such complex dune fields — with multiple types of dunes — form in areas with especially abundant sands. (Image credit: NASA; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Dune Fields From Space

An astronaut captured this image of the Oyyl Dune Field in Kazakhstan from the International Space Station. To the south and east of the dune field (right and lower parts of image) there are fluvial floodplains, sources of sediment that feed the dunes. With sufficient wind and sand sources, the dune field has grown in a topographic low spot roughly 90 meters lower than the surrounding steppes. Dark specks scattered across the sands are clusters of vegetation, a sign that the dunes may get anchored rather than continue to shift in the wind. (Image credit: NASA; via NASA Earth Observatory)

How Dunes Form

On its face, the idea that sand and wind can come together to form massive mountainous dunes seems bizarre. But dunes — and their smaller cousins, ripples — are everywhere, not just on Earth but on other planetary bodies where fine particles and atmospheres interact. In this video, Joe Hanson gives a great overview of sand dynamics, beginning with what sand is, how it moves, and what it can ultimately form. It’s well worth a watch, even if you know a little about dunes already; I know I learned a thing or two! (Image and video credit: Be Smart)

Ice and Dunes

Although dunes are usually associated with scorching climates, they can form in any desert, including in the frozen steppes of western Mongolia. This sunrise photo, taken by an astronaut aboard the ISS, shows Ulaagchinii Khar Nuur. The ice-covered Khar Nuur Lake surrounds two islands, Big and Small Avgash, and cold dunes form textured streaks on either side. The low sun angle accentuates the dunes, making every rippling crest clear. (Image credit: NASA; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Dune Invasion

Migrating sand dunes can encounter obstacles both natural and manmade as they move. Dunes — both above ground and under water — have been known to bury roads, pipelines, and even buildings. A recent experimental study looks at which obstacles a dune will cross and which will trap it in place. Their set-up consists of a narrow channel built in a ring, essentially a racetrack for dunes. Flow is driven by a series of paddles that rotate opposite the tank’s rotation.

The team studied obstacles of different shapes and sizes relative to their dunes, and they found that dunes were generally able to cross obstacles that were smaller than the dune. Obstacles larger than the dune would trap it in place, and, for obstacles close to the same size as the dune, round obstacles were easier to cross whereas sharp-angled ones tended to trap the dune.

The idealized nature of their experiment means that their results aren’t immediately applicable to the complex dunes of the outside world, but the study will be an important touchstone for those predicting dune behavior through numerical simulation. Studies like those require experimental cases to validate their baseline simulations. (Image credit: top – J. Bezanger, figure – K. Bacik et al.; research credit: K. Bacik et al.; via APS Physics)