By now you’ve probably come across some blog posts and news articles about a new pre-print study looking at the aerodynamics of running and the potential exposure to exhaled droplets. And you may also have seen articles questioning the accuracy and validity of such simulations. I’ve had several readers submit questions about this, so I dug into both the research and the criticisms, and here are my thoughts:

Is this study scientifically valid?

I’ve seen a number of complaints that since this paper hasn’t been peer-reviewed, we shouldn’t trust anything about it. That seems like an unreasonable overreaction to me considering how many studies receive press attention prior to their actual peer-reviewed publication. This is not a random CFD simulation produced by someone who just downloaded a copy of ANSYS Fluent. This work comes from a well-established group of engineers specializing in sports aerodynamics, and long-time readers will no doubt recognize some of their previous publications. Over the past decade, Blocken and his colleagues have become well-known for detailed experimental and simulation work that indicates larger aerodynamic effects in slipstreams than what we generally recognize.

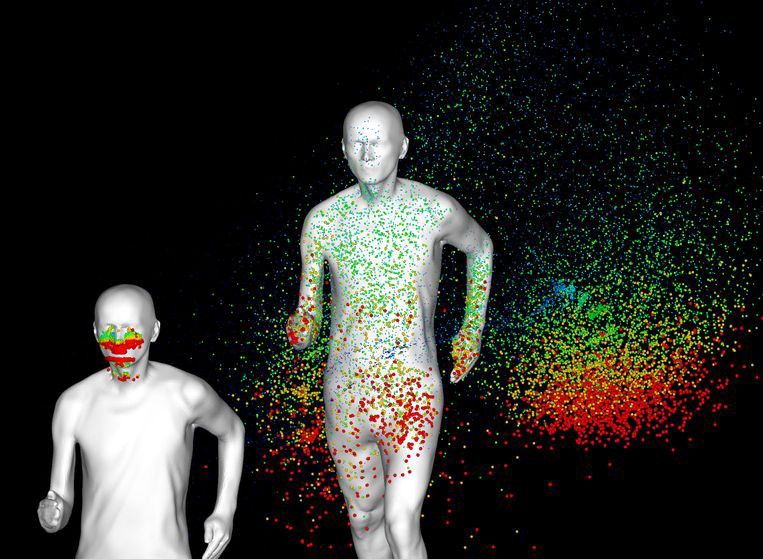

In this paper, they lay out previous (biological) studies related to SARS and droplet exhalation; they use those papers and several wind tunnel studies to validate computational models of droplet evaporation and runner aerodynamics; and then they use those inputs to simulate how a cloud of exhaled droplets from one runner affects someone running alongside, behind, or in a staggered position relative to the first runner.

In other words, their work includes all the components one would expect of a scientific study, and it makes scientifically justifiable assumptions with regard to its methods. (That’s not, mind you, to say that no one can disagree with some of those choices, but that’s true of plenty of peer-reviewed work as well.) All in all, yes, this is a scientifically valid study, even if it has not yet undergone formal peer-review*.

Can simulations actually tell us anything about virus transmission?

One complaint I’ve seen from both biologists and engineers is that simulations like these don’t actually capture the full physics and biology involved in virus transmission. While I agree with that general sentiment, I would point out two important facts:

1) Blocken et al. acknowledge that this is not a virology study and confine their scientific results to looking at what happens physically to droplets when two people are moving relative to one another. Whether those droplets can transmit disease or not is a question left to biological researchers.

2) Most medical and biological research also does not account for the physics of droplet transmission and transport. For the past century, this research has focused almost exclusively on droplet sizes, with the assumption that large droplets fall quickly and small droplets persist a little longer. To my knowledge, some of the only work done on the actual physics of the turbulent cloud produced by coughing or sneezing comes from Lydia Bourouiba’s lab at MIT. And, to me, one of the fundamental conclusions from her work is that droplets (especially small ones) can persist a lot longer and farther than previously assumed. Can those droplets facilitate transmission of COVID-19? The general consensus I’ve seen expressed by medical experts is no, but, to my knowledge, that is based on opinion and assumption, not on an actual scientific study.

The bottom line

In my opinion, there’s a big disconnect right now between the medical/biological community and the engineering community. To truly capture the physics and biology of COVID-19 transmission requires the expertise and cooperation of both. Right now both sides are making potentially dangerous assertions.

Honestly, based on what I know about aerodynamics, I am personally skeptical as to whether 6 ft of physical separation is truly enough; whether it is or not seems to depend on how transmissible the novel coronavirus is through small droplets, which, again, to my knowledge, is unestablished.

Should we leave more distance than 6ft between us when exercising outdoors? Absolutely. Aerodynamically, it makes perfect sense that following in someone’s slipstream would put you inside their droplet cloud, which needs time and space to disperse. Personally, I’ve sidestepped the question entirely by doing all my cycling indoors while quarantined.

tl;dr: There are a lot of open questions right now about COVID-19 transmission and what qualifies as safe distancing, but it’s smarter to err on the side of more distancing. Don’t hang close to others when running or cycling outdoors.

(Image and research credit: B. Blocken et al.; submitted by Corky W. and Wendy H.)

*I will add that, with my training, I have and do occasionally peer-review studies such as this one, and I read the full paper with the same sort of critical eye I would turn to a paper I was asked to review.