The Seoul Aquarium is now home to an enormous crashing wave, courtesy of design company d’strict. Check out several different views of the anamorphic illusion in their video above. There’s no word on the techniques used to generate the animation, but it’s certainly a cool visual! (Image and video credit: d’strict; via Colossal)

Tag: waves

Captured by Waves

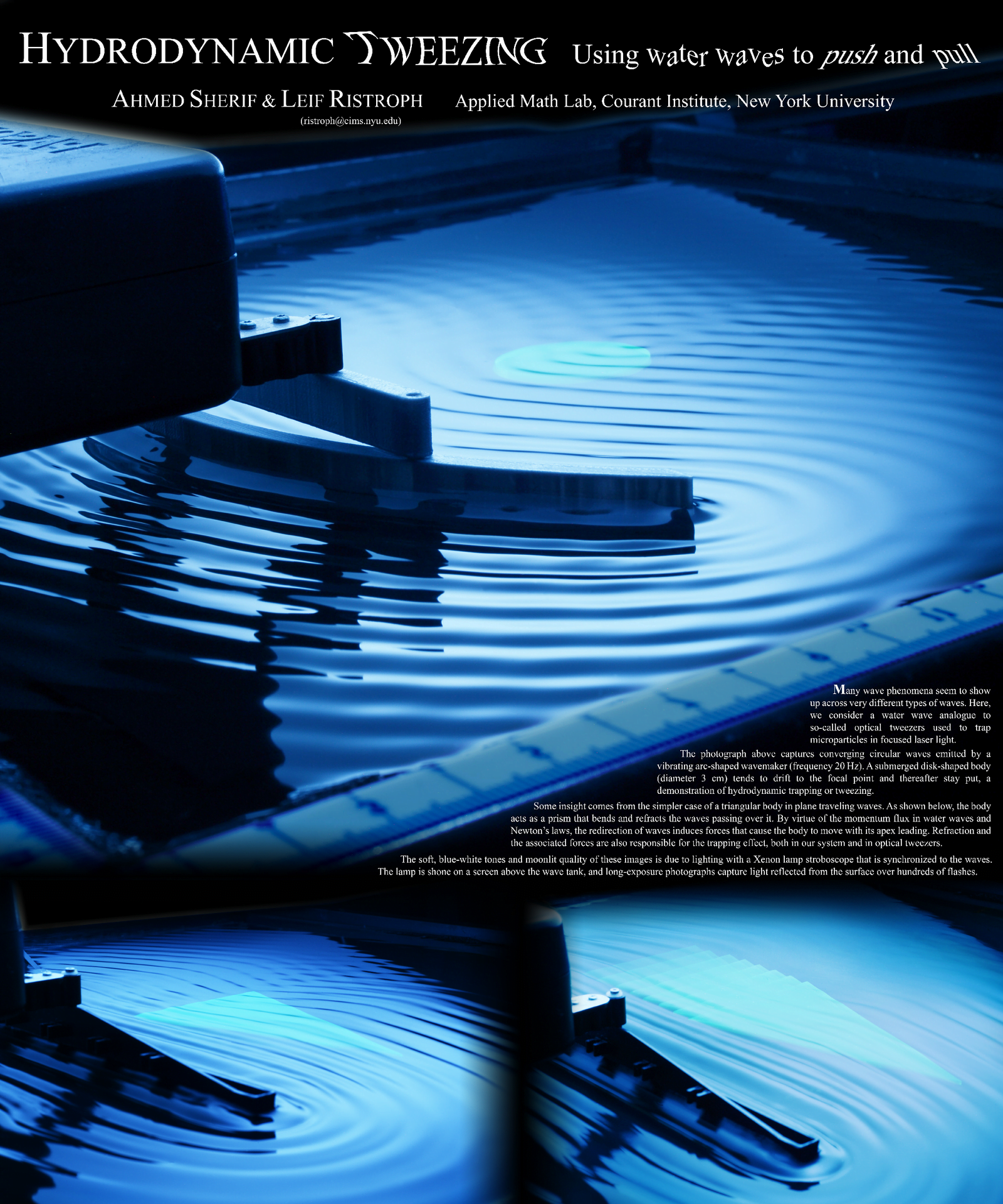

Acoustic levitation and optical tweezers both use waves — of sound and light, respectively — to trap and control particles. Water waves also have the power to move and capture objects, as shown in this award-winning poster from the 2019 Gallery of Fluid Motion. The central image shows a submerged disk, its position controlled by the arc-shaped wavemaker at work on the water’s surface. The complicated pattern of reflection and refraction of the waves we see on the surface draws the disk to a focal point and holds it there.

On the bottom right, a composite image shows the same effect in action on a submerged triangular disk driven by a straight wavemaker. As the waves pass over the object, they’re refracted, and that change in wave motion creates a flow that pulls the object along until it settles at the wave’s focus. (Image and research credit: A. Sherif and L. Ristroph)

Testing Waves in High Gravity

Where waves crash and meet, turbulence is inevitable. But exactly how large waves interact — whether in the ocean, in plasma, or the atmosphere — is far from understood. A new experiment is teasing out a better physical understanding by tweaking a variable that’s been hard to change: gravity.

To do so, the researchers conduct their experiments in a large-diameter centrifuge (shown above) where they can create effective gravitational forces as high as 20 times Earth’s gravity. This increases the range of frequencies where gravity-dominated waves occur by an order of magnitude.

By studying this extended frequency range, the authors found something unexpected: the timescales of wave interactions did not depend on wave frequency, as predicted by theory. Instead, those interactions were dictated by the longest available wavelength in the system, a parameter set by the size of the container. It will be interesting to see if future work can confirm that result with even larger containers. (Image credit: ocean waves – M. Power, others – A. Cazaubiel et al.; research credit: A. Cazaubiel et al.; via APS Physics; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

The Best of FYFD 2019

2019 was an even busier year than last year! I spent nearly two whole months traveling for business, gave 13 invited talks and workshops, and produced three FYFD videos. I also published more than 250 blog posts and migrated all 2400+ of them to a new site. And, according to you, here are the top 10 FYFD posts of the year:

- The perfect conditions make birdsong visible

- Pigeons are impressive fliers

- The water anole’s clever method of breathing underwater

- 100 years ago, Boston was flooded with molasses

- The BZ reaction is some of nature’s most beautiful chemistry

- The labyrinthine dance of ferrofluid

- 360-degree splashes

- The extraordinary flight of dandelion seeds

- Dye shows what happens beneath a wave

- Bees do the wave to frighten off predators

Nature makes a strong showing in this year’s top posts with five biophysics topics. FYFD videos also had a good year: both my Boston Molasses Flood video and dandelion flight video made the top 10!

If you’d like to see more great posts like these, please remember that FYFD is primarily supported by readers like you. You can help support the site by becoming a patron, making a one-time donation, or buying some merch. Happy New Year!

(Image credits: birdsong – K. Swoboda; pigeon take-off – BBC Earth; water anole – L. Swierk; Boston molasses flood – Boston Public Library; BZ reaction – Beauty of Science; ferrofluid – M. Zahn and C. Lorenz; splashes – Macro Room; dandelion – N. Sharp; dyed wave – S. Morris; bees – Beekeeping International)

Reader Question: Cross Sea

Reader Matt G asks:

[What’s] going on here?

Why’s the pattern square? Just a special case of waves traveling in different directions, and this photo happened to catch some at right angles to one another?

You’re not far off, Matt! This is an example of cross sea, where wave trains moving in different directions meet. Like most ocean waves, these waves originated from wind moving over the water. As the wind blows, it transfers energy to the water, disturbing what would otherwise be a smooth surface and setting up a series of waves. Oftentimes, these waves can outlast the wind that generates them and travel over long distances of open water as a swell.

Cross seas occur when two of these wave systems collide at oblique angles. They’re most obvious in shallow waters like those seen here, where the depth makes their criss-cross pattern clearer. Another name for them is square waves, and although the pattern isn’t a perfect square, it’s usually fairly close. If the waves aren’t separated by a large angle, they’re more likely to merge than to create this sort of pattern.

Neat as cross seas look, they’re quite dangerous, both to ships and swimmers. Ships are built to tackle waves head-on and don’t fare well when they’re forced to take waves from the side. For swimmers, the danger is a little different. Cross seas create intense vorticity under the surface and can generate stronger than usual riptides that sweep the unwary out to sea. (Image credit: M. Griffon)

Diamond-Shaped Waves

Strong winds blowing across Lake Michigan created this diamond-shaped wave pattern after the incoming waves reflected off the breakwater on the right. The formal name for these waves are clapotis gaufré, meaning “waffled standing waves”. As seen in the animation above, the waves aren’t perfect standing waves; otherwise they would stay in one place rather than propagating toward shore. This happens because the angle of reflection is not exactly 90 degrees.

As neat as clapotis gaufré waves look, they’re a significant problem for the builders of coastal infrastructure. The waves generate vortices underwater that are extremely good at eroding underlying sediment. (Image and video credit: T. Wenzel; via EPOD; submitted by Vince D.)

Reader Question: Waves Breaking

As a follow-up to the recent waves post, reader robotslenderman asks:

What does it look like when the wave breaks? And why do waves sometimes push us back? Why are we able to ride them?

I wasn’t able to find an equivalent breaking wave version of that dyed wave – side note: readers with flumes, please feel free to make one and share it! – but here’s an undyed breaking wave for our reference.

Waves break, or get that white, frothy look, when they reach shallower water. In the previous post, the waves we saw were effectively deep-water waves, so they didn’t change in height as they rolled across the tank. Here there’s an incline to simulate a beach, which causes the water to slow down and steepen. That forms the characteristic curl of a plunging breaker, seen here.

At the beach, a wave runs out of water to pass through and all the energy that wave was carrying has to go somewhere. Some is lost as heat, some turns into the sound of that classic crashing wave, and a lot of it gets dissipated as turbulence that pushes us, sand, shells, and anything else its way.

As for why we can ride waves, there’s some special physics at play when it comes to surfing. To catch a wave, a surfer has to paddle hard to get up to the wave’s speed just as it reaches them. Too slow and the wave will just pass them by, leaving them bobbing more or less in place. (Image credit: T. Shand, source)

How Waves Travel

When playing in the surf, it’s easy to imagine that the incoming waves are a wall of water crashing into the shore. And, in a way they are, but probably less so than you imagine. Waves travel through a medium, whether it’s solid or fluid, but for the most part, they’re not translating the medium itself. You can see that in the animation above by watching the dye beneath the surface. The passing waves don’t cause much mixing in the dye, and though their passage distorts the underlying water, we see that everything returns more or less to its starting position once the wave has passed. (Image credit: S. Morris, source)

Doing the Wave

Not everything that behaves like a fluid is a liquid or a gas. In particular, groups of organisms can behave in a collective manner that is remarkably flow-like. From schools of fish to fire-ant rafts, nature is full of examples of groups with fluid-like properties.

One of the most mesmerizing examples are these giant honeybee colonies, which essentially do “the wave” to frighten away predators like wasps. Researchers are still trying to understand and mimic the way these groups coordinate such behaviors. Can even complicated patterns be generated by a simple set of rules an individual animal follows? That’s the sort of question active matter researchers investigate. Check out the video above to see a whole cliff’s worth of bee colonies shimmering. (Image and video credit: BBC Earth)

Transporting Droplets

Transporting droplets easily and reliably is important in many microfluidic applications. While this can be done using electric fields, those fields can impact biological characteristics researchers are trying to measure. As an alternative, a group of researchers have developed the concept of “mechanowetting,” a technique that uses surface tension forces to hold droplets on a traveling wave.

Now visually, it’s a bit tough to see what’s going on here. In the animations, it looks like the droplets are just sticking to a moving surface, but that’s an illusion. The surface the droplet is sitting on is fixed and unmoving. It’s a thin silicone film that covers a ridged conveyor belt. The belt underneath can (and does) move. This creates a traveling wave. Instead of that wave simply passing beneath the droplet, it triggers an internal flow and restoring force that helps the drop follow the wave. The effect is strong enough that small droplets are even able to climb up vertical walls or stick upside-down. (Image, research, and submission credit: E. de Jong et al.)