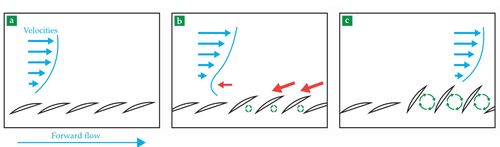

We’ve seen previously just how fluid dynamically impressive sharks are on the outside, but today’s study demonstrates that they’re just as incredible on the inside. Researchers used CT scans of more than 20 shark species to examine the structure of their intestines. Sharks have spiral intestines that come in four different varieties; two of those types look like a stacked series of funnels (either pointing upstream or downstream). These funnel-filled spirals, the researchers found, are incredibly good at creating uni-directional flow without any moving parts, much like a Tesla valve does. The spiral structure also seems to slow down digestion, which may factor into the shark’s ability to go long periods between meals. Incredibly, the fossil record indicates that spiral intestines — in some form — evolved in sharks about 450 million years ago — before mammals even existed! Clearly we engineers are way behind sharks when it comes to controlling flows!

(Image credit: top – D. Torobekov, scan – S. Leigh; research credit: S. Leigh et al.; via NYTimes; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)