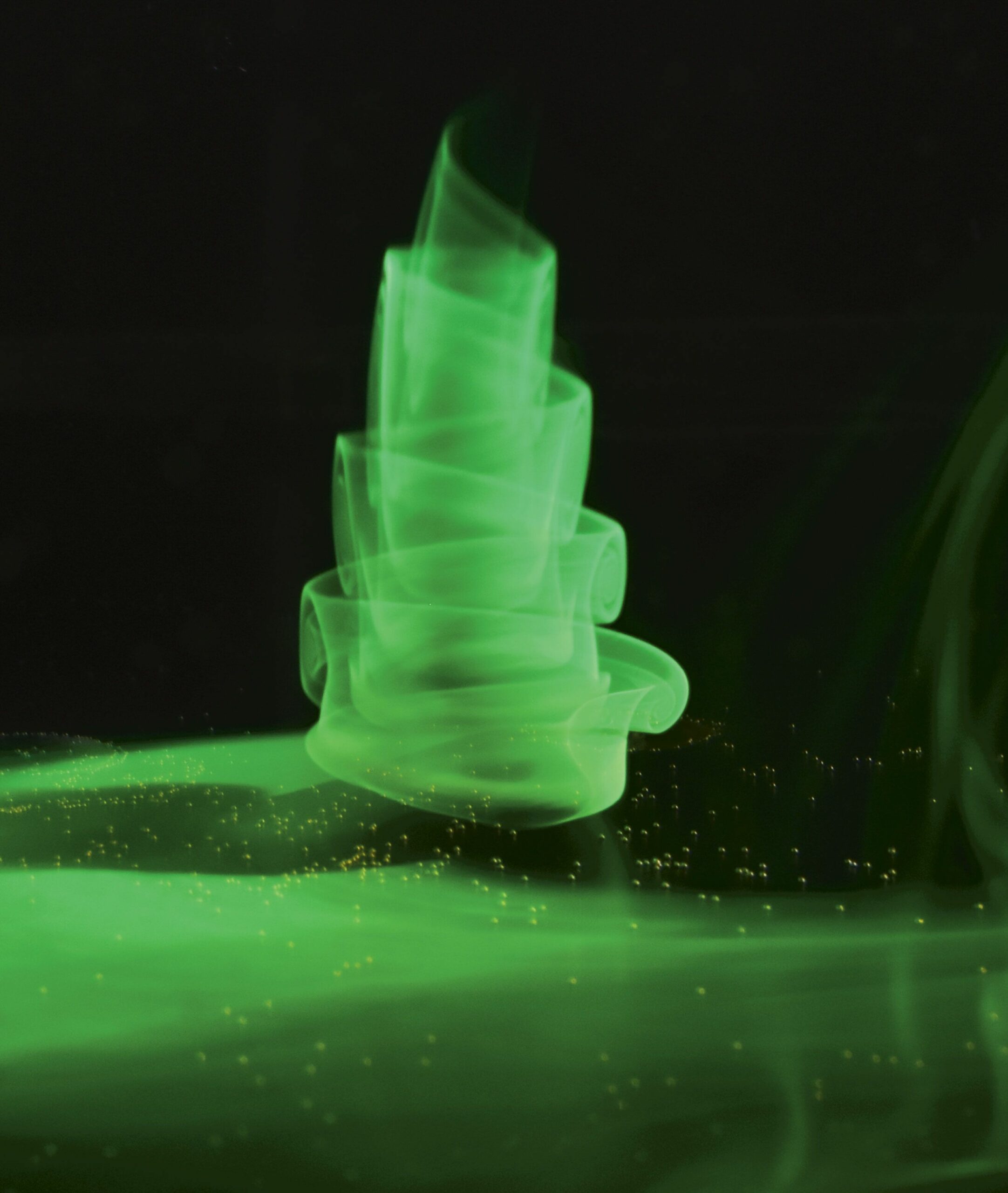

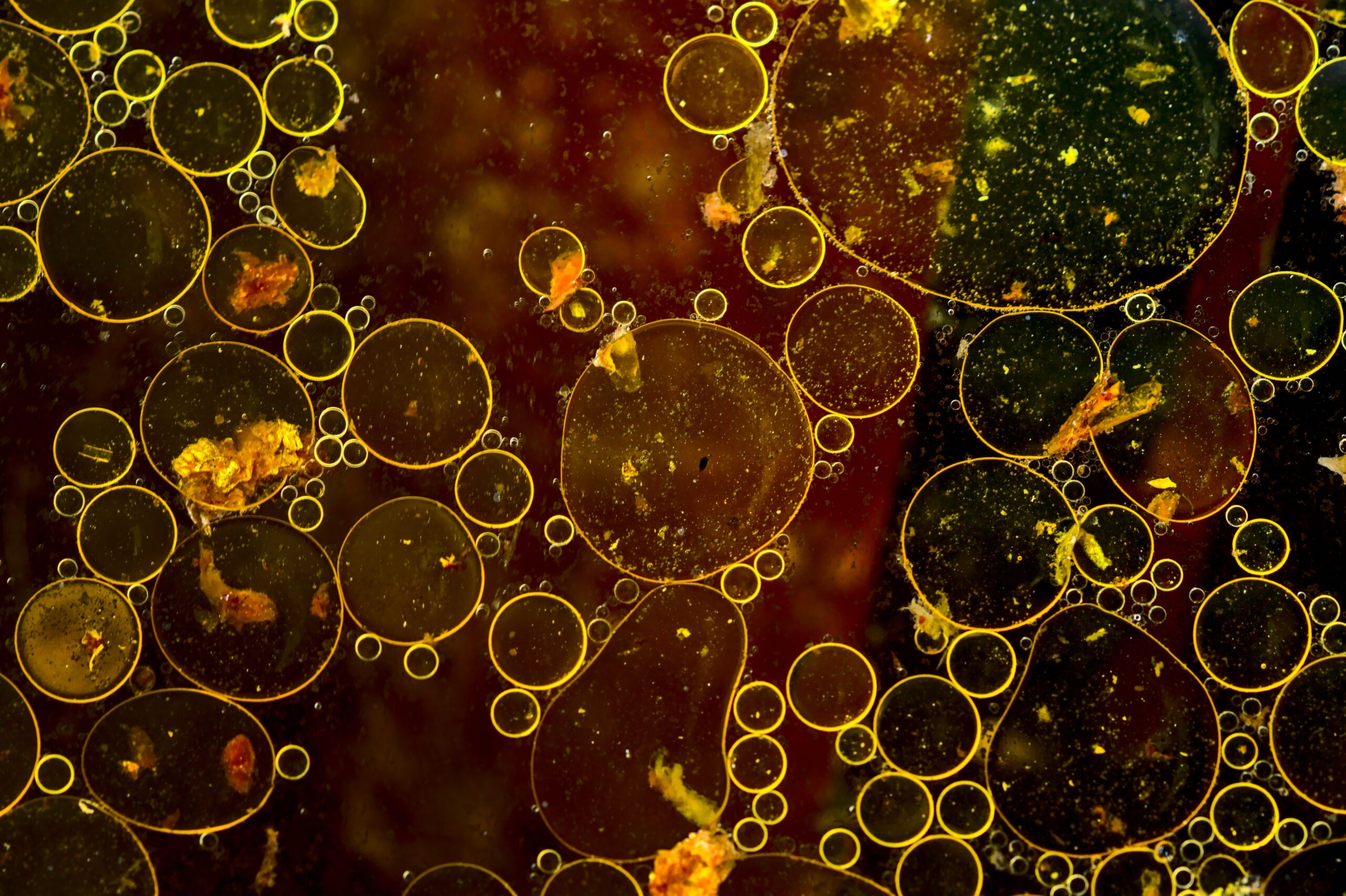

If you’ve ever stirred a cup of tea with loose leaves in it, you’ve probably noticed that the leaves tend to swirl into the center of the cup in a kind of inverted whirlpool. At first, this behavior can seem counter-intuitive; after all, a spinning centrifuge causes denser components to fly to the outside. In this video, Steve Mould steps through this phenomenon and how the balance of pressures, velocities, densities, and viscosity cause the effect. (Note that Mould uses the term “drag,” but what he’s really referring to is the boundary layer across the bottom of the container. But who wants to explain a boundary layer in a video when they can avoid it?) (Video and image credit: S. Mould)