Artist Alberto Seveso returns to his colorful ink plumes (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), but this time with a twist. Here, Seveso took ink injected in water and digitally altered it, adding texture and shaping the ink to mimic the shapes of coral reefs. The results are stunning, though I confess a few of them remind me of mushrooms or organs more than reefs. (Image credit: A. Seveso; via Colossal)

Tag: plumes

Dust Storms

Hot, dry berg winds swept down from the Namibian highlands and sent these plumes of dust flying out to the Atlantic coast. Another plume — white instead of brown — marks salt dust from the Etosha Pan salt flat. The dust and salt become aerosol particles in the atmosphere — seeds for raindrops to form. Coastal towns sometimes need construction equipment to deal with the drifting sand from these storms, but these storms are small compared to Saharan dust storms. Those storms are so large that their dust influences the weather on the other side of the Atlantic. (Image credit: W. Liang; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Modeling Wildfires With Water

Turbulence over a burning forest can carry embers that spread the wildfire. To understand how wildfire plumes interact with the natural turbulence found above the forest canopy, researchers modeled the situation in a water flume. Dowel rods acted as a forest, with turbulence developing naturally from the water flowing past. For a wildfire, the researchers used a plume of warmer water, which buoyancy lofted into the turbulence over their model forest.

The experiment used to model wildfire flows. Dowel rods represent the forest and a plume of warm water (right side; distorting the background) represents the wildfire. The dark device in the foreground is a probe used to measure turbulence. The flow over the forest canopy naturally forms side-by-side rolls of air rotating around a horizontal axis. As the buoyant plume rises, it can be torn apart by these rollers, as well as carried downstream. Varying the turbulence, they found, did not affect the average trajectory of the plume. But the more intense the turbulence, the greater the vertical fluctuations in the plume. Those large variations, they concluded, could lift more embers into stronger winds that distribute them further and spread a fire faster. (Image credit: wildfire – M. Brooks, experiment – H. Chung and J. Koseff; research credit: H. Chung and J. Koseff; via APS Physics)

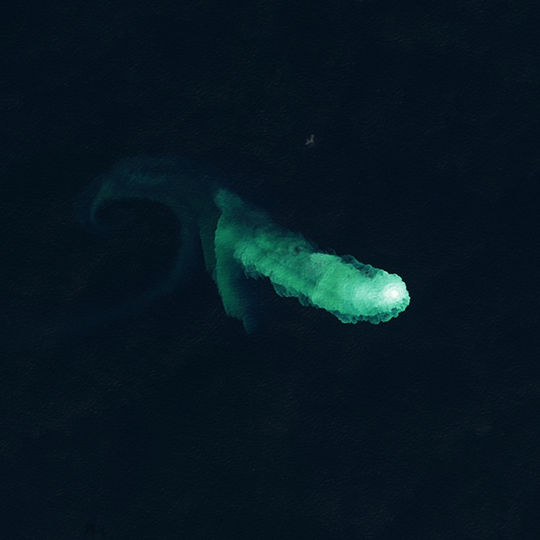

Submarine Volcano

This pale green plume signals the activities of Kaitoku, an underwater seamount near Japan. Periodic activity picked up there in August 2022 and continued into the new year. The rising plume likely consists of superheated acidic seawater mixed with particulates, sulfur, and rock fragments. Underwater volcanoes like this one are thought to account for up to 80 percent of our planet’s volcanic activity. (Image credit: L. Dauphin; via NASA Earth Observatory)

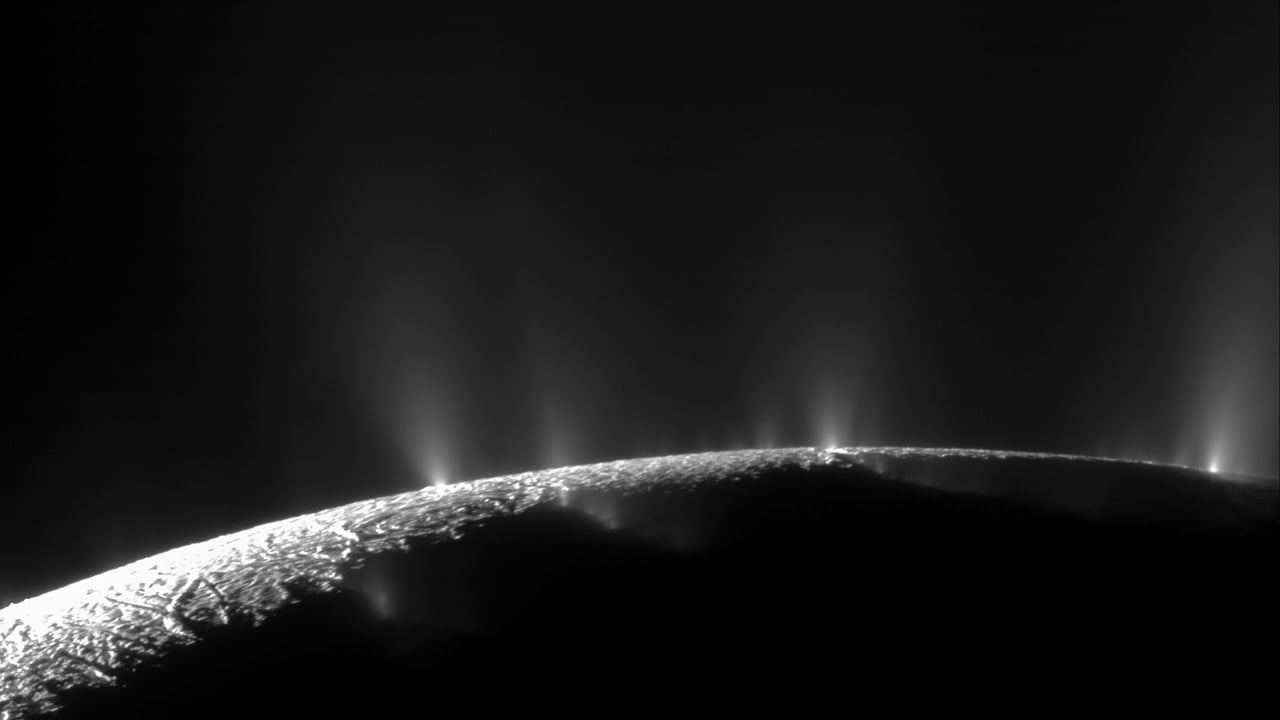

Founts of Enceladus

In its exploration of Saturn, Cassini discovered that the moon Enceladus is home to icy eruptions. Beneath its shell of ice, Enceladus has a global ocean of salty liquid water. The average thickness of the ice is 20 kilometers, putting the ocean seemingly out of reach — except at the moon’s southern pole, where icy plumes of ocean water jet out.

Here, where the ice is thinnest, the tidal forces Enceladus experiences from Saturn and its fellow moon Dione break through the ice. As the cracks open and close, liquid from the ocean sprays out, freezing into plumes that Cassini measured. Plans are underway for new missions that prioritize further sampling of Enceladus’ ocean. For now, we can only imagine what hides in its interior ocean. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI; for more, see M. Manga and M. Rudolph)

Toilet Plumes

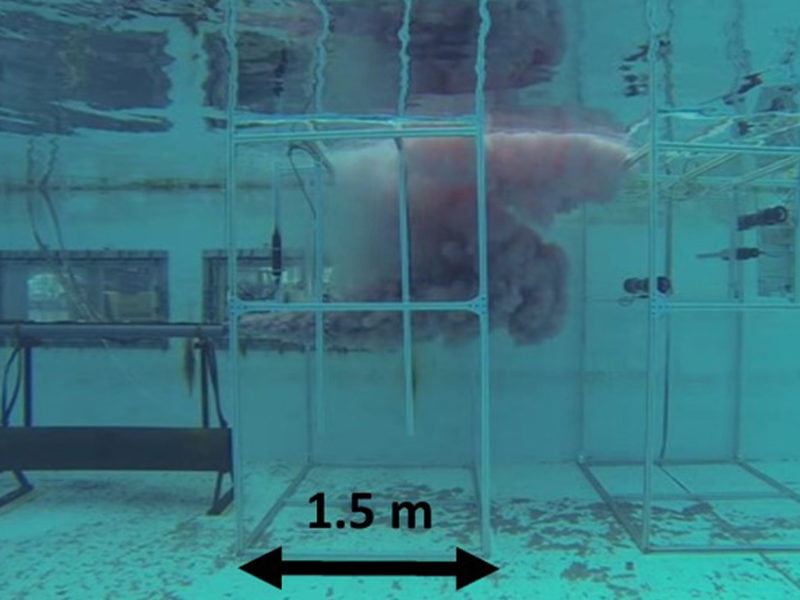

Toilet flushes are gross. We’ve seen it before, though not in the same detail as this study. Here, researchers illuminate the spray from the flush of a typical commercial toilet, like those found in many public restrooms. They found that flushing generates a plume of droplets that reaches 1.5 meters in under 8 seconds, producing many thousands of droplets across a range of sizes.

The experiments were conducted in a ventilated lab space, and the flushes involved only clean water — no fecal matter or toilet paper — so they don’t perfectly mimic the confines of a public toilet stall. But the implications are still pretty gross. Without a lid to contain the flush’s spray, these energetic toilets are spraying droplets capable of carrying COVID, influenza, and other nastiness all over our bathrooms. (Image and research credit: J. Crimaldi et al.; via Gizmodo)

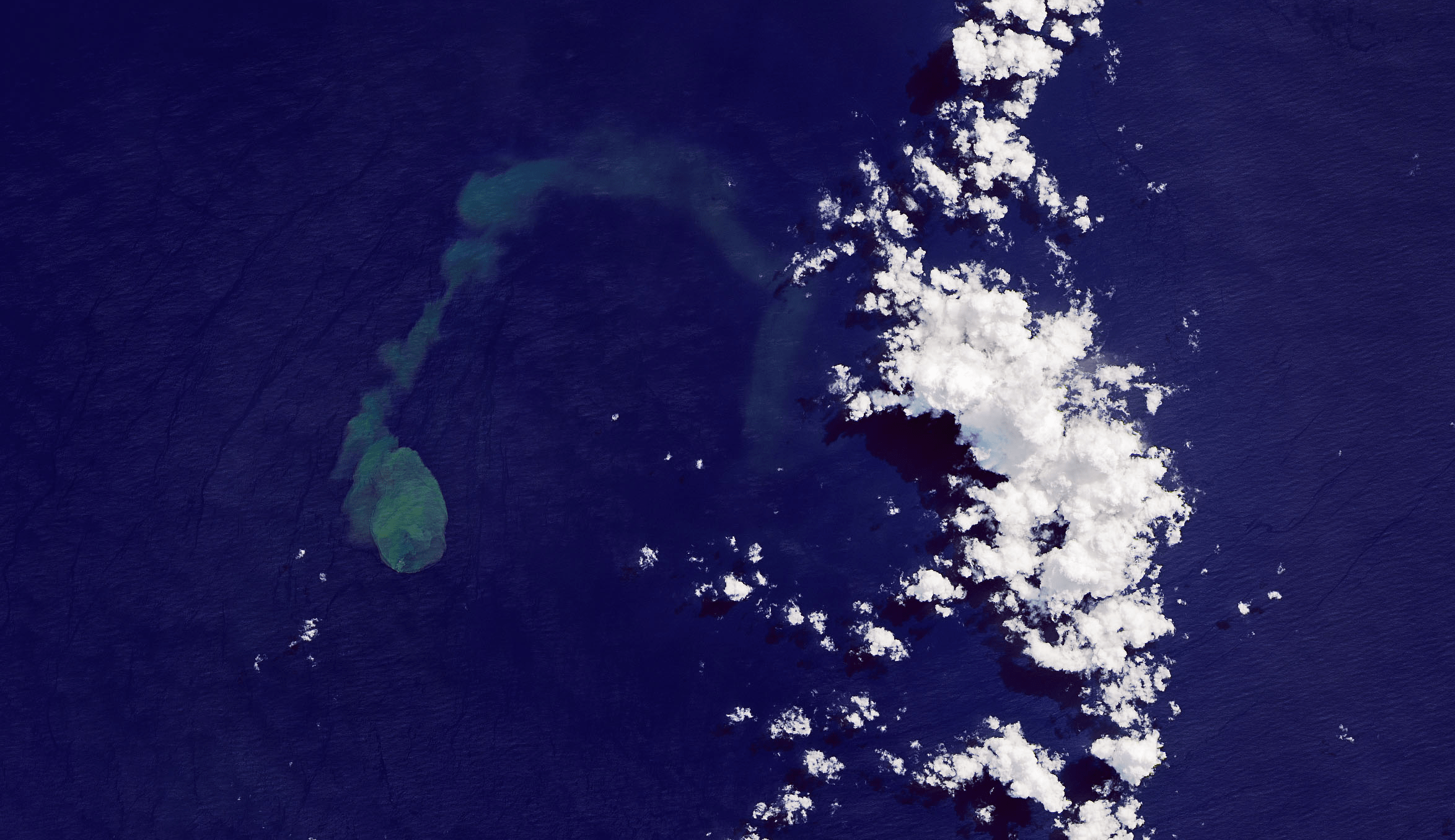

Submarine Eruptions

The green-blue plume on the left of this satellite image is an eruption from Kavachi, an underwater volcano in the Solomon Islands. Kavachi’s crest is currently estimated to lie 20 meters below the surface, with its base at a depth of 1.2 kilometers. Eruptions are quite common at the volcano, but that doesn’t stop wildlife — like hammerhead sharks! — from making the crater their home. Over the last century, Kavachi’s eruptions have repeatedly formed small islands at the surface, but they were quickly eroded away by wave action. (Image credit: J. Stevens/NASA/USGS; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Oil in Water

In the decade since the Deepwater Horizons oil spill, scientists have been working hard to understand the intricacies of how liquid and gaseous hydrocarbons behave underwater. The high pressures, low temperatures, and varying density of the surrounding ocean water all complicate the situation.

Released hydrocarbons form a plume made up of oil drops and gas bubbles of many sizes. Large drops and bubbles rise relatively quickly due to their buoyancy, so they remain confined to a relatively small area around the leak. Smaller drops are slower to rise and can instead get picked up by ocean currents, allowing them to spread. The smallest micro-droplets of oil hardly rise at all; instead they remained trapped in the water column, where currents can move them tens to hundreds of kilometers from their point of release. (Image and research credit: M. Boufadel et al.; via AGU Eos; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Landings Beyond Earth

With planning for manned and unmanned missions to the Moon, Mars, and many asteroids underway, engineers are using numerical simulations to understand how spacecraft thrusters interact with planetary surfaces. Most practical data for this problem comes from the Apollo program and is of limited use for current missions. Recreating a Martian landing on Earth isn’t straightforward, either, given our higher gravity. Thus, supercomputers and numerical simulation are the best available tool for understanding and predicting how the plumes from a spacecraft’s thrusters will interact with a surface and what kind of blowback the spacecraft will need to withstand. (Video credit: U. Michigan Engineering; research credit: Y. Yao et al.; submission by Jesse C.)

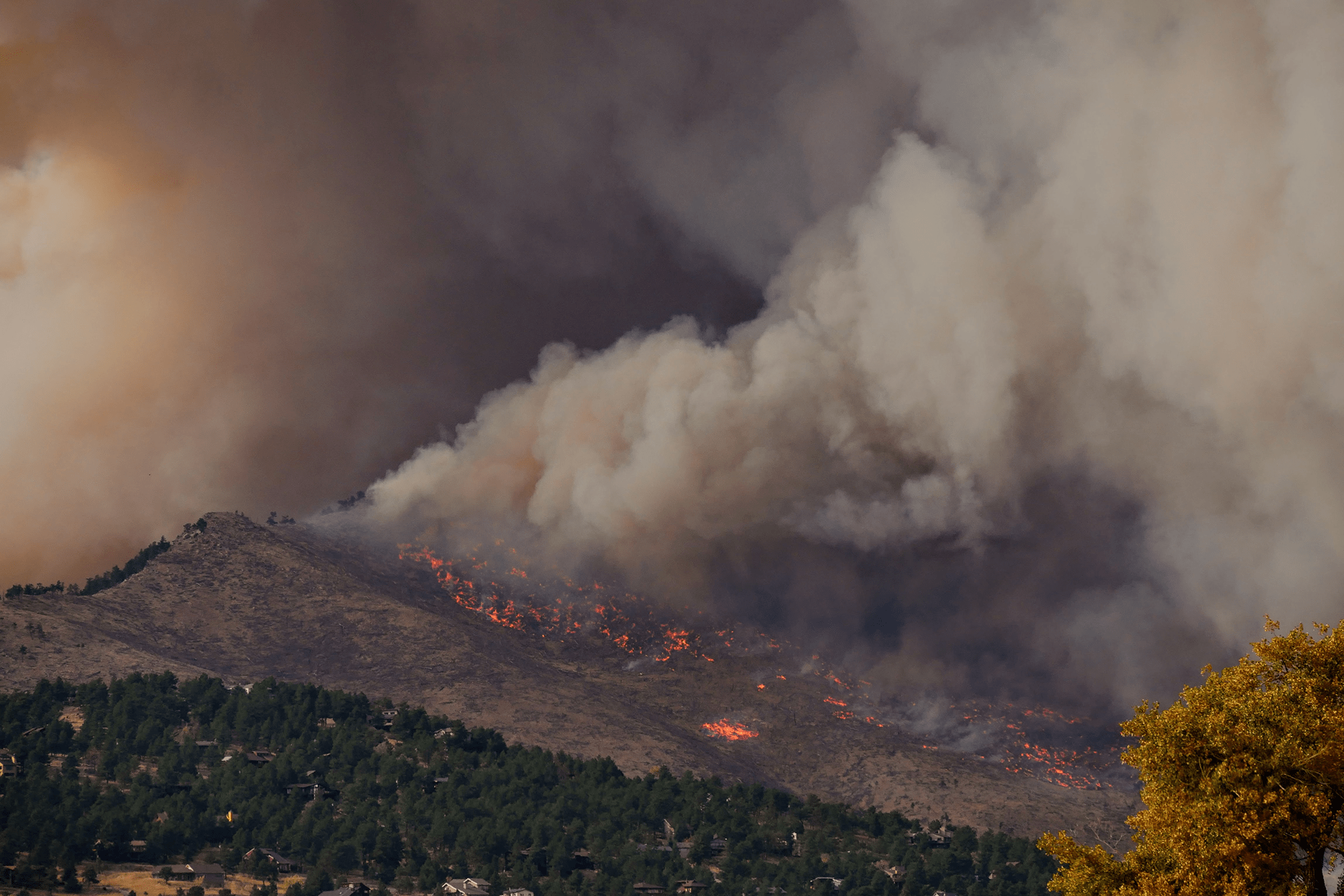

Stratospheric Effects of Wildfires

Australia’s bushfires from earlier this year are offering new insights into how pyrocumulonimbus clouds can affect our stratosphere. A massive, uncontrolled blaze between December 29th and January 4th generated a towering, turbulent cloud of smoke like the one shown above.

Using meteorological data, a new study shows this enormous cloud initially rose to 16 km in altitude, then began a months-long trek that circled the globe. The smoke plume ultimately stretched to over 1,000 km wide and reached a record altitude of over 31 km. Inside the plume, concentrations of water vapor and carbon monoxide were several hundred percent higher than normal stratospheric air.

Researchers found the plume extremely slow to dissipate, possibly due to strong rotational winds surrounding it. This is the first time scientists have observed these shielding winds, and work is still underway to determine how and why they formed. (Image credit: M. Macleod/Wikimedia Commons; research credit: G. Kablick III et al.; via Science News; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)