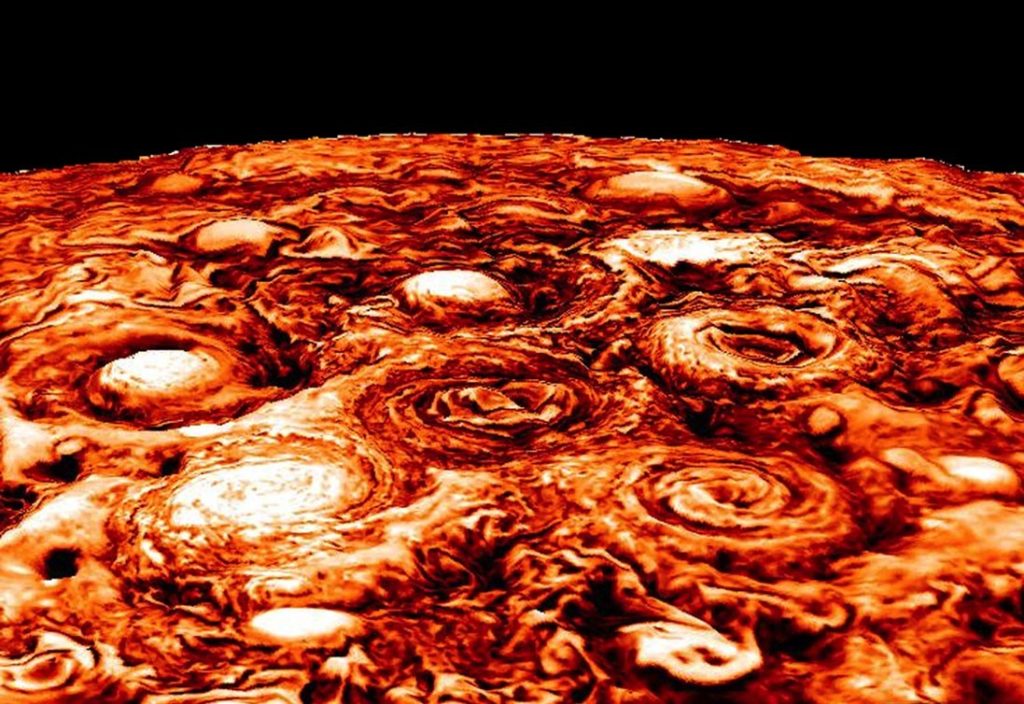

Jupiter’s atmosphere is full of enduring mysteries, and its poles are no exception. Instruments aboard the Juno spacecraft have gotten a better look at Jupiter’s North and South poles than any previous mission, and what they’ve found raises even more questions. Both of Jupiter’s poles feature a central cyclone ringed by other, similarly-sized cyclones. The North pole has eight outer cyclones (top image), while the South pole has five (bottom image), shown above in infrared. Despite being close enough that their spiral arms intersect, the cyclones don’t seem to be merging into something like Saturn’s polar hexagon. For now, scientists don’t know how this arrangement formed or why it persists, but the longer Juno can study the vortices up close, the more we’ll learn. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM; research credit: A. Adriani et al.; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Tag: planetary science

Juno’s Citizen Science

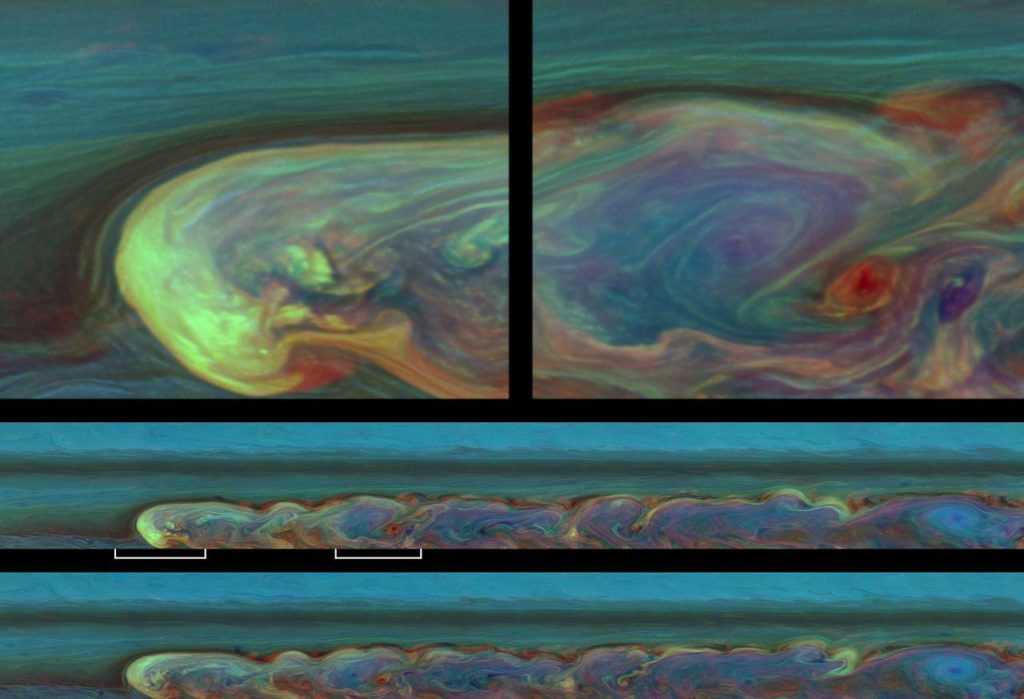

The Juno mission’s JunoCam has been producing stunning photos each time the spacecraft swoops past Jupiter. The instrument has a planning team, but its primary use is for citizen scientists, who have been suggesting images to take each orbit and have been processing those images. Most of the photos we see are like the one on the left above – photos that have been heavily color-enhanced to highlight details. The image on the right shows what Jupiter would look like to the human eye. Look closely, and you’ll catch many of the same colors and shapes in both photos.

At a recent conference, a member of JunoCam’s team presented scientific results that have come from the instrument, including analysis of Jupiter’s polar storm systems (8 vortices for the north pole and 5 for the south), tantalizing hints at Jovian equivalents to earthly cloud types, and more. She also announced a new Analysis page where members of the public can both see the science in progress and participate first-hand! (Image credit: NASA / SwRI / MSSS / G. Eichstädt / S. Doran; NASA / JPL-Caltech / SwRI / MSSS / B. Jónsson; via E. Lakdawalla; submitted by jshoer)

Forming Craters

Asteroid impacts are a major force in shaping planetary bodies over the course of their geological history. As such, they receive a great deal of attention and study, often in the form of simulations like the one above. This simulation shows an impact in the Orientale basin of the moon, and if it looks somewhat fluid-like, there’s good reason for that. Impacts like these carry enormous energy, about 97% of which is dissipated as heat. That means temperatures in impact zones can reach 2000 degrees Celsius. The rest of the energy goes into deforming the impacted material. In simulations, those materials – be they rock or exotic ices – are usually modeled as Bingham fluids, a type of non-Newtonian fluid that only deforms after a certain amount of force is applied. An everyday example of such a fluid is toothpaste, which won’t extrude from its tube until you squeeze it.

The fluid dynamical similarities run more than skin-deep, though. For decades, researchers looked for ways to connect asteroid impacts with smaller scale ones, like solid impacts on granular materials or liquid-on-liquid impacts. Recently, though, a group found that liquid-on-granular impacts scale exactly the way that asteroid impacts do. Even the morphology of the craters mirror one another. The reason this works has to do with that energy dissipation mentioned above. As with asteroid impacts, most of the energy from a liquid drop impacting a granular material goes into something other than deforming the crater region. Instead of heat, the mechanism for dissipation here is the drop’s deformation. The results, however, are strikingly alike.

For more on how asteroid impacts affect the moon and other bodies, check out Emily Lakdawalla’s write-up, which also includes lots of amazing sketches by James Tuttle Keane, who illustrates the talks he hears at conferences! (Image credits: J. Keane and B. Johnson; via the Planetary Society; additional research and video credit: R. Zhao et al., source; submitted by jpshoer)

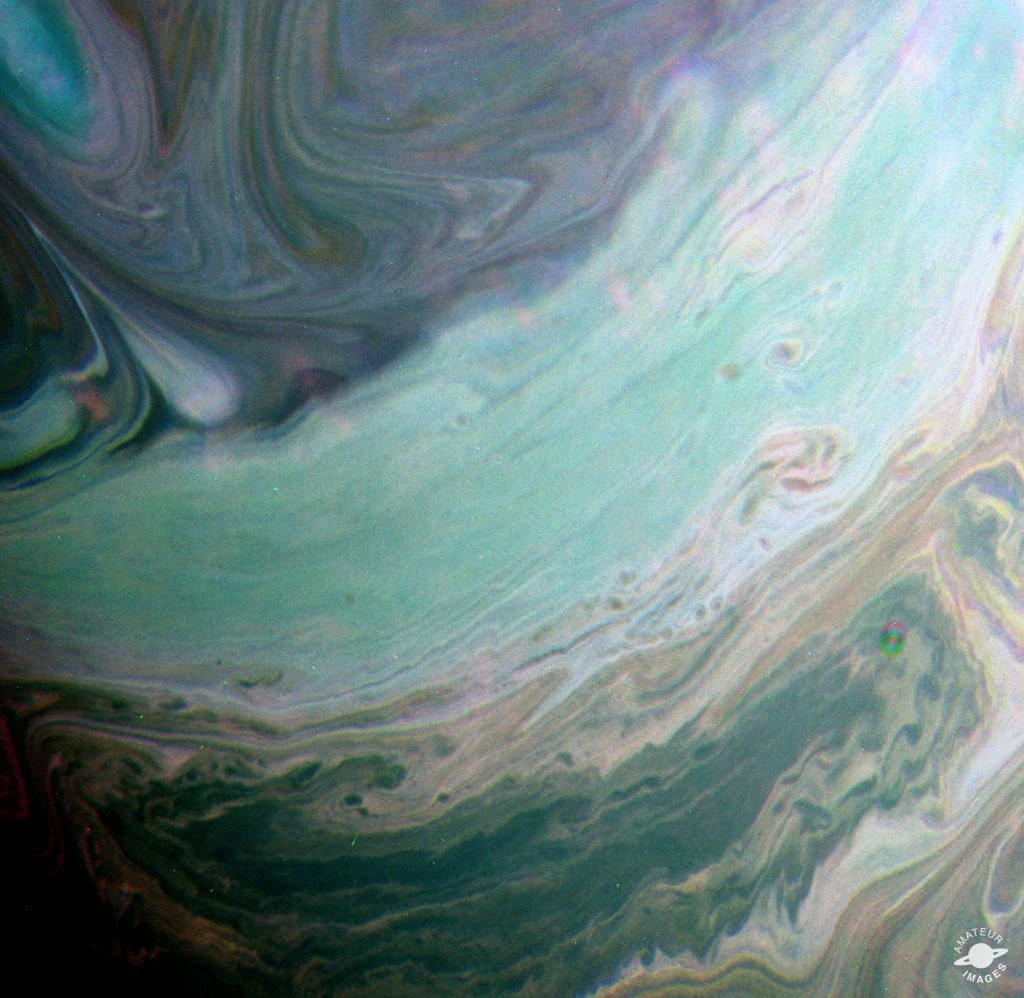

Jupiter’s Atmosphere

Jupiter’s atmosphere is fascinatingly complex and stunningly beautiful. This close-up from the Juno spacecraft shows a region called STB Spectre, located in Jupiter’s South Temperate Belt. The bluish area to the right is a long-lived storm that’s bordering on very different atmospheric conditions to the left. Shear from these storms moving past one another creates many of the curling waves we see in the image. These are examples of the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability, which generates ocean waves here on Earth, creates spectacular clouds in our atmosphere, and is even responsible for waves in galaxy clusters. Check out some of the other amazing images Juno has sent back of our solar system’s largest planet. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/R. Tkachenko; via Gizmodo)

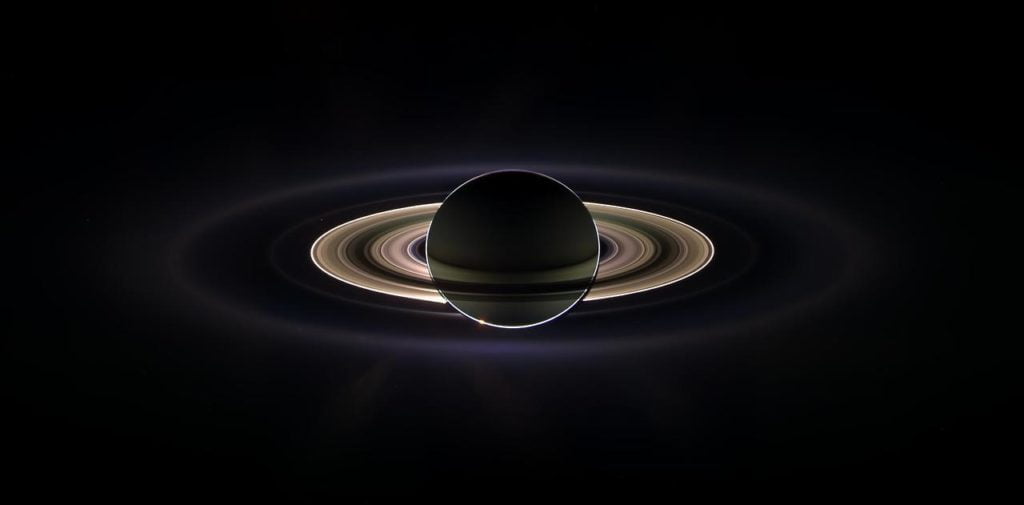

Farewell, Cassini!

Tomorrow one of the most prolific and beloved spacecraft missions will come to an end when the Cassini spacecraft makes its final plunge into Saturn. After nearly 20 years in space and 13 years orbiting Saturn, the Cassini mission is close to running out of fuel. To prevent the craft from contaminating one of Saturn’s moons – which its mission revealed may harbor the ingredients for life – mission operators are instead sending it on a fatal dive into the gas giant.

Cassini has and will continue to provide a trove of scientific insights about Saturn and its environs. It has given us front-row seats to a storm that wrapped around the entire planet. It shed new light on Saturn’s spectacular hexagonal polar vortex and showed us the beauty of auroras on other planets. Cassini also showed us that Saturn’s moon Titan has stable hydrocarbon lakes at its surface, fed by methane rains and driven by processes unfamiliar to terrestrial ones. It also gave us paths for future exploration by documenting plumes of water ejected from Enceladus’ icebound oceans.

Cassini also holds a special place in my heart. It launched while I was in middle school, reached Jupiter while I was in college, and collected data throughout my postgraduate research career. It was an inspiration for my undergraduate spacecraft mission design projects, and it provided fun and exciting fluid dynamical discoveries throughout my time writing FYFD. It’s my favorite mission (sorry, Mars rovers, New Horizons, Dawn, and Juno!) and likely to remain so for years to come.

So thank you, Cassini, and many thanks to all the scientists, engineers, and operators who’ve worked on the mission during the decades from its conception to completion. You did a hell of a job. Godspeed, Cassini! (Photo credits: NASA/JPL)

P.S. – Tonight I’ll be helping kick off the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony. You can tune into the live webcast here. The ceremony officially starts at 6 PM Eastern time, but I recommend tuning in early, especially if you want to catch my full spiel. – Nicole

The Winds of Mars

The Martian atmosphere is scant compared to Earth’s, but its winds still sculpt and change the surface regularly. The average atmospheric pressure on Mars is only 0.6% of Earth’s, and the density is similarly low at 1.7% of Earth’s. Despite this thinness, Martian winds are still substantial enough to shift sands on a daily basis, as shown above. These two images were taken one Martian day apart, showing how sand ripples moved and how the Curiosity rover’s tracks can be quickly obscured. Part of the reason Mars’ scant atmosphere is still so good at moving sand is that Martian gravity is roughly one-third of ours; if the sand is lighter, it doesn’t take as much force to move! (Image credit: NASA/JPL-CALTECH/MSSS)

A Real Tatooine

Since at least the release of “Star Wars”, we have wondered what life would be like on a circumbinary planet – a planet orbiting two stars. In the past few decades, we have discovered several such planets, but we are still in the early days of modeling the climate of these worlds. One recent study uses the stars of the Kepler 35 system, which are only slightly less luminous than our sun, to explore the climate of an Earth-like water planet.

According to the study, this fictional planet would maintain Earth-like habitability at a distance of 1.165–1.195 astronomical units from its suns’ center of gravity – just a little further out than our own orbital distance. Variables like the planet’s mean global surface temperature and precipitation vary with two distinct periods – the time required for the stars to orbit one another and the time it takes for the planet to orbit its stars. Both factors affect how much sunlight the planet receives. The planet’s climate response to these changes is complex and varies depending on location, but the overall variations observed in the climate are small. It does show, however, that places like Tatooine don’t have to be desert planets! (Image credit: Tatooine – Star Wars; Kepler 35 system – L. Cook; research credit: M. Popp and S. Eggl)

Perijove

The Juno spacecraft continues to send back incredible photos of Jupiter’s atmosphere. This video animates images from the sixth close pass of Jupiter to give you a sense of what Juno sees as it swoops by our system’s largest planet. The trajectory passes from the north pole to the south, showing Jupiter’s whitish zones, dark belts, and massive storms. Up close Jupiter looks like an Impressionist painting, all vortices and shear instabilities. The large white spots you see are enormous counterclockwise rotating vortices known as anticyclones – many of them larger than our entire planet. (Video credit: NASA / SwRI / MSSS / G. Eichstädt / S. Doran)

Gravity Waves on Mars

It may look like grainy, black and white static from a 20th-century television, but this animation shows what may be the first view of gravity waves seen from the ground on another planet. The animation was stitched together from photos taken by the Mars Curiosity rover’s navigation camera, and it shows a line of clouds approaching the rover’s position.

Gravity waves are common on Earth, appearing where disturbances in a fluid propagate like ripples on a pond. In the atmosphere, this can take the form of stripe-like wave clouds downstream of mountains; internal waves under the ocean are another variety of gravity wave. If these are, in fact, Martian gravity waves, they are likely the result of wind moving up and over topography, much like their Terran counterparts. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/York University; research credit: J. Kloos and J. Moores, pdf; via Science; h/t Cocktail Party Physics)

Ice Bridges

During winter, Canada’s Arctic Archipelago, home of the Northwest Passage, generally fills with sea ice. These ice bridges form in the long and narrow straits between islands. A new paper models ice bridge formation and break-up, showing that ice bridges can only form when ice floating in the strait is sufficiently thick and compact. To form a bridge, wind must first push the ice together and then frictional forces between individual pieces of ice must be large enough to resist wind or water driving them apart. As temperatures drop, the individual ice chunks can then freeze together into solid sheets until summer returns.

The existence of a critical thickness and density of the ice field for ice bridge formation has important implications for climate change. As Arctic temperatures warm for longer periods, these waters may no longer generate ice of sufficient thickness and quantity for ice bridges to form. Since ice bridges serve as important oases for marine mammals and sea birds and help isolate Arctic sea ice from warmer waters, their loss will have a profound impact on both Arctic ecology and global climate. (Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory; research credit: B. Rallabandi et al.; via Physics Buzz)