Viewing fluids through a macro lens makes for an incredible playground. In “Galaxy Gates”, Thomas Blanchard and the artists of Oilhack explore a colorful and dynamic landscape of paint, oil, and glitter. The nucleation of holes and the breakdown of sheets to filaments and droplets plays a major role in the visuals. The surface layer is constantly peeling away to reveal what’s going on underneath. In many cases this initial motion settles into a field of oil-rimmed droplets floating like planets against a colorful galactic backdrop. Watch carefully in the second half of the video, and you can even catch a few instances of a stretched ligament of fluid breaking into a string of satellite drops, like at 1:51. Check out some of Blanchard’s previous work here and here. (Video credit: Oilhack and T. Blanchard; GIFs and h/t to Colossal)

Tag: miscibility

Acrylic and Oil

Photographer Alberto Seveso is well-known for ink in water art, some of which FYFD has featured previously (1, 2, 3). More recently, he’s been experimenting with alternative methods, dropping fluids like acrylic paint into sunflower oil. The effect is quite different but no less beautiful. Because the paint and oil are immiscible, the boundaries between the two fluids are much more clearly defined and highlighted in an iridescent sheen. Instead of appearing like billowing waves of silk, the paint forms abstract and alien shapes driven by gravity, inertia, and density differences. For many more great examples, check out Seveso’s website. (Photo credit: A. Seveso)

Self-Propelling Drops

Droplets of acetone deposited on a bath of warm water can float along on a Leidenfrost-like vapor layer. The droplets are self-propelling, too, thanks to interactions between the acetone and water. Acetone can dissolve in water, and when acetone vapor beneath the drop gets absorbed into the water bath, it lowers the local surface tension. That drop in surface tension creates a pull in the direction of a higher surface tension; this is what is known as the Marangoni effect. Because of that flow in the direction of higher surface tension, the acetone drop accelerates away. (Image credit: S. Janssens et al., source)

“Oil Spill”

In “Oil Spill” artist Fabian Oefner explores the shapes and colors of oil floating atop water. An old adage tells us that oil and water don’t mix, but this is not perfectly true. Especially in low concentrations, oil can mix slightly with water, which is why the edges of Oefner’s creations become fuzzy and break down. For the most part, though, the thin layer of oil spreads across the water’s surface, its slight variations in thickness casting the different iridescent colors we observe – just the same as a soap bubble’s iridescence. The colorful patterns are a snapshot of motion in the oil; in some places it radiates outward, pulled by the stronger surface tension of water. In other places it forms plumes and swirls that may be the result of temperature variations or other disquiet motion in the surrounding water or air. (Image credits: F. Oefner)

Colors in Macro

Milk, acrylic paints, soap, and oil – all relatively common fluids, but together they form beautiful mixtures worth leaning in to enjoy. Variations in surface tension between the liquids cause much of the motion we see. Soap, in particular, has a low surface tension, which causes nearby colors to get pulled away by areas with higher surface tension, behavior also known as the Marangoni effect. Adding oil creates some immiscibility and lets you appreciate both the coalescence and fragmentation of the fluids. And finally, there’s one of my favorite sequences, where bubbles start popping in slow motion. As the bubble film ruptures, fluid pulls away, breaking into ligaments and then a spray of droplets as the bubble disintegrates. (Video credit: Macro Room; via Gizmodo)

“Memories of Paintings”

In “Memories of Paintings,” Thomas Blanchard gives us an up-close view of fluids and mixing. It’s a calming and curious video made from combinations of paint, oil, oat milk, and soap. The fluids feather and intertwine, driven by differences in surface tension. Paint gets encapsulated by immiscible oil to create little islands of color that float and dance against the background. It’s a fun journey through effects that we witness daily but rarely take the time to watch. (Video credit: T. Blanchard; via Gizmodo)

Daily Fluids, Part 3

A lot of the fluid dynamics in our daily lives centers around the preparation and consumption of food. (And in its digestion afterward, but that’s another story!) Here are a few examples of fluid dynamics you might not have realized you’re an expert on:

Low Reynolds Number Flows

This is a fancy way of discussing the motion of syrup, honey, and other thick and viscous fluids we interact with in our lives. These flows are typically slow moving and exhibit some neat properties like coiling or being possible to unstir.

Immiscible Fluids

Oil and water don’t mix, a fact anyone familiar with salad dressings or marinades is well aware of. The way around this is to shake them up! This disperses droplets of the oil within the water (or vinegar or whatever) to create an emulsion. While not truly mixed, it does make for more pleasant eating.

Multiphase Flows

Multiphase flows are ones containing both liquid and gaseous states. Boiling is an example we often see in our daily lives, though carbonated beverages, water sprayers, and sneezes are other common ones.

Leidenfrost Effect

The Leidenfrost effect occurs when liquid is introduced to a surface that is much, much hotter than its boiling point. Part of the liquid instantly vaporizes, leaving droplets to skitter around on a thin vapor layer. This is most often seen around the stove and in skillets. (And, yes, it does qualify as a multiphase flow!)Tune in all week for more examples of fluid dynamics in daily life. (Image credit: S. Reckinger et al., source)

P.S. – I’m at VidCon (@vidconblr) this year! If you are, too, come say hi and get an FYFD sticker 😀

Emulsion Impact

Emulsions – mixtures of two immiscible fluids – are quite common; the oil and vinegar combination used in many salad dressings is one. The image sequence above shows the first 800 microseconds of the impact of a similarly emulsified droplet. The outer drop, seen on the left, consists of a water/glycerin mixture, and inside the drop are 20 smaller perfluorohexane droplets. These smaller droplets are denser and tend to settle toward the bottom of the outer drop. When the compound droplet hits a solid surface, it spreads in a spectacular starburst pattern that depends on the number and location of interior droplets. You can see a similar impact in motion here. (Image credit: J. Zhang and E. Li; source: C. Josserand and S. Thoroddsen)

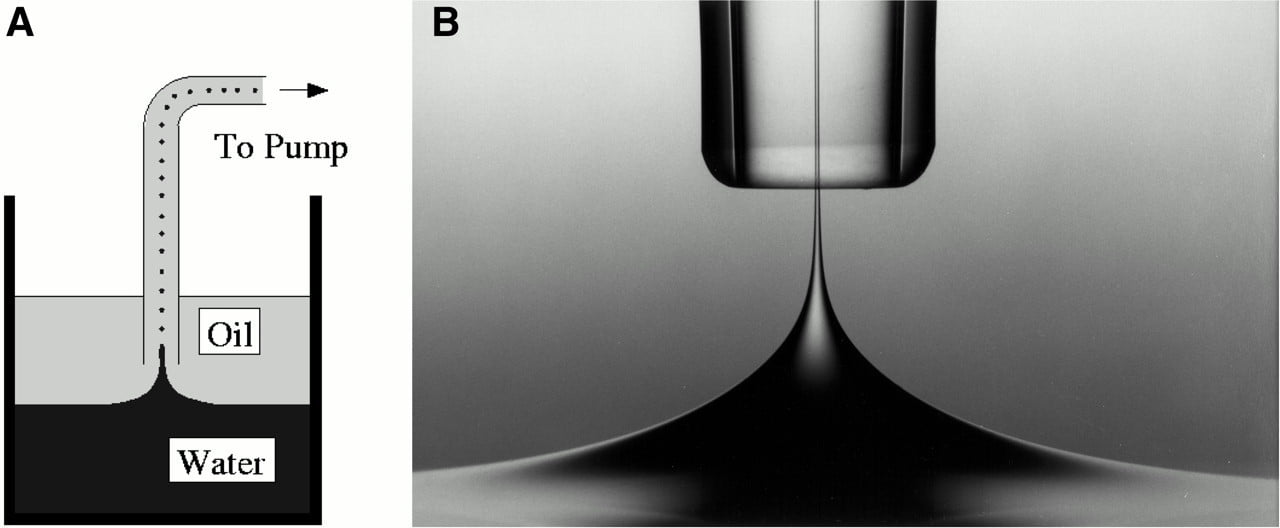

Selective Suction

A thin spout of water is drawn up through a layer of oil in the photo on the right. This simple version of the selective withdrawal experiment is illustrated in Figure A, in which a layer of viscous oil floats above a layer of water. A tube introduced in the oil sucks fluid upward. At low flow rates, only the oil will be drawn into the tube, but as the flow rate increases (or the tube’s height above the water decreases), a tiny thread of water will be pulled upward as well. The viscous outer fluid helps suppress instabilities that might break up the inner fluid, and their relative viscosities determine the thickness of the initial spout. In this example, the oil is 195 times more viscous than the water. (Photo credit: I. Cohen et al.)

“Pacific Light”

This lovely video from Ruslan Khasanov showcases the beautiful interplay of surface tension, diffusion, and immiscibility in common fluids. With soy sauce, oil, ink, soap, and a little gasoline, he creates a mesmerizing world of color and motion. It’s a great reminder of the wonders that populate our daily lives, if we just look closely enough to see them. (Video credit: R. Khasanov; via Wired; submitted by Trevor)