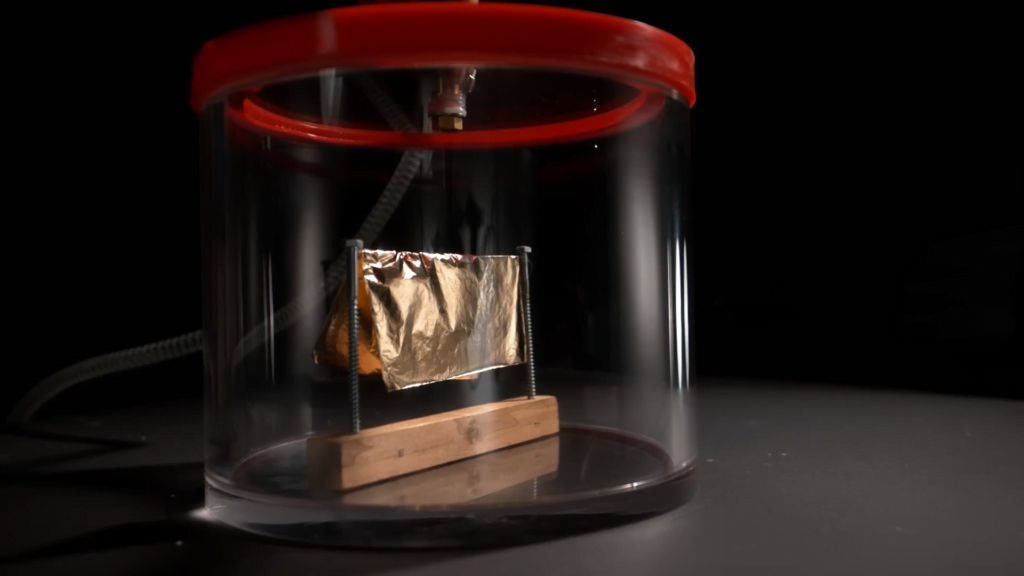

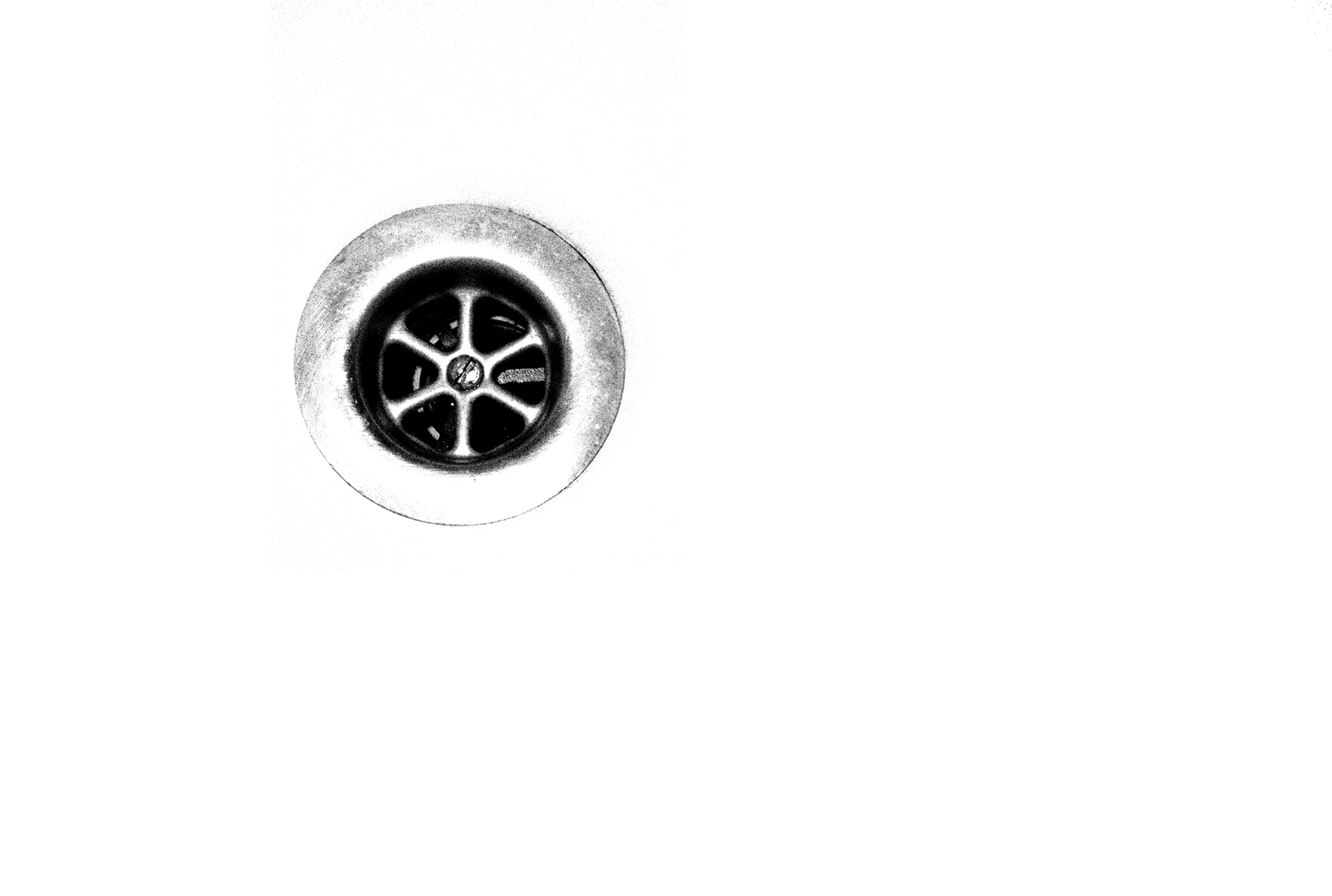

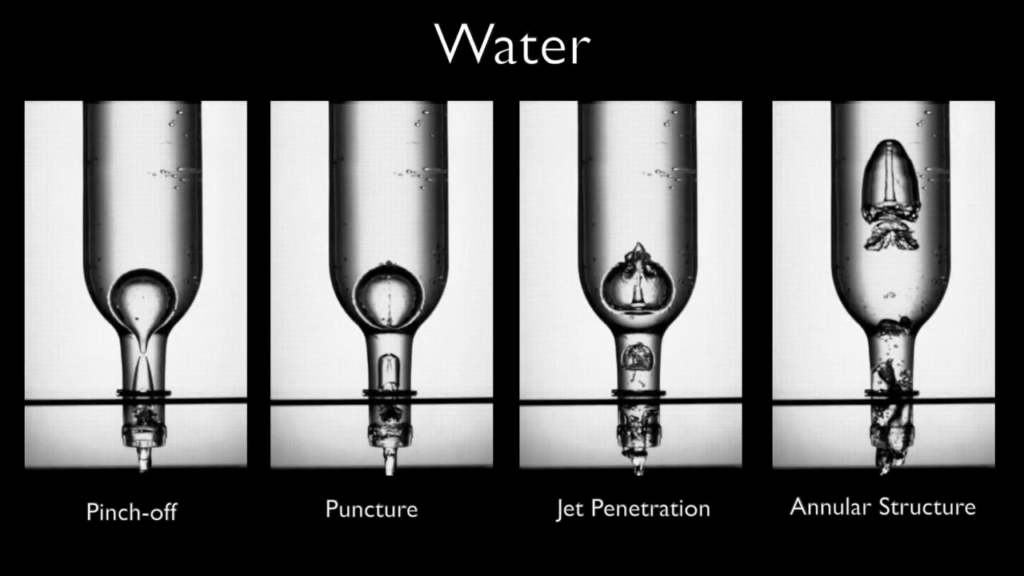

In competition diving, athletes chase a rip entry, the nearly splash-less dive that sounds like paper tearing. Part of a successful rip dive comes in the impact, where divers try to open a small air cavity with their hands that their entire body then enters. But the other key component happens below the surface, where divers bend at the hips once underwater. This maneuver enlarges the air cavity underwater and disrupts the formation of a jet that would typically shoot back upwards. Done properly, the result is an entry with little to no splash at the surface and a panel full of pleased judges. (Image credits: top – A. Pretty/Getty Images, other – E. Gregorio; research credit: E. Gregorio et al.; via Science News; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Related topics: Rip entry physics, how pelicans dive safely, and how boobies plunge dive

This post marks the end of our Olympic coverage for this year’s Games, but if you missed any previous entries, you can find them all here.