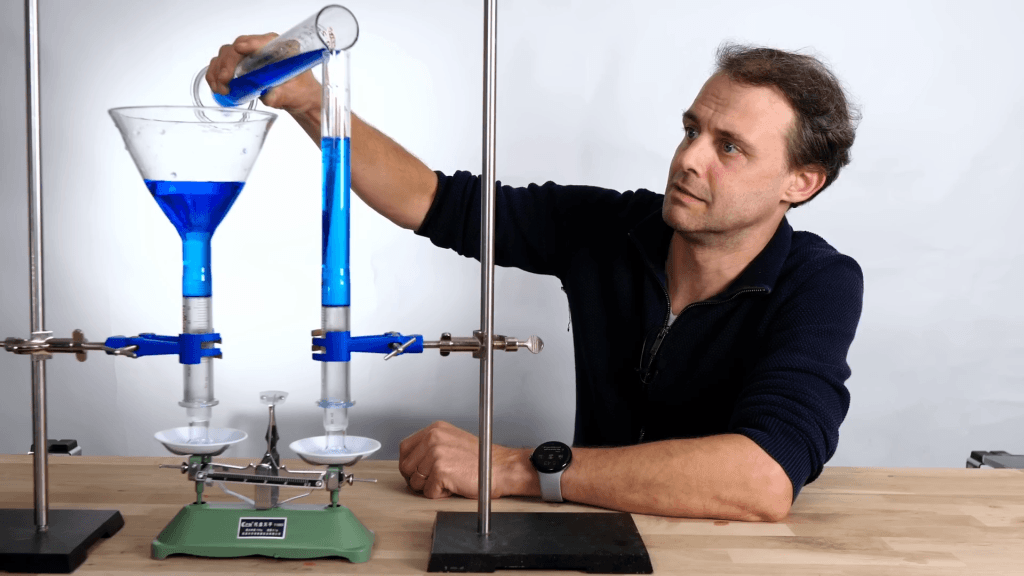

Engineering classes often discuss hydrostatics–the physics of non-moving water–before they cover fluid dynamics and its flows. But hydrostatics is plenty challenging on its own, as Steve Mould demonstrates in this video looking at how hydrostatic pressure depends on depth (and, not, as our intuition might suggest, on shape). As always, he has some nice countertop-scale demos to go with it. (Video and image credit: S. Mould)

Tag: hydrostatics

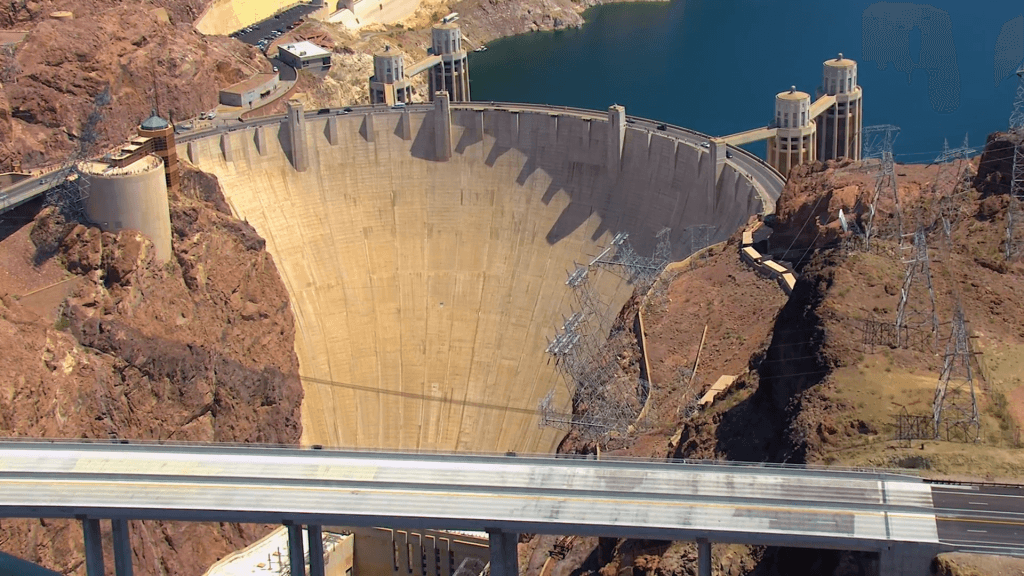

The Forces on an Arch Dam

Although they’re iconic, arch dams like the Hoover Dam are relatively unusual. In this Practical Engineering video, Grady looks at the forces a dam needs to withstand and where and why an arch dam is useful. It’s a good reminder that even water that (for the most part) isn’t moving is still a challenge to deal with. (Video and image credit: Practical Engineering)

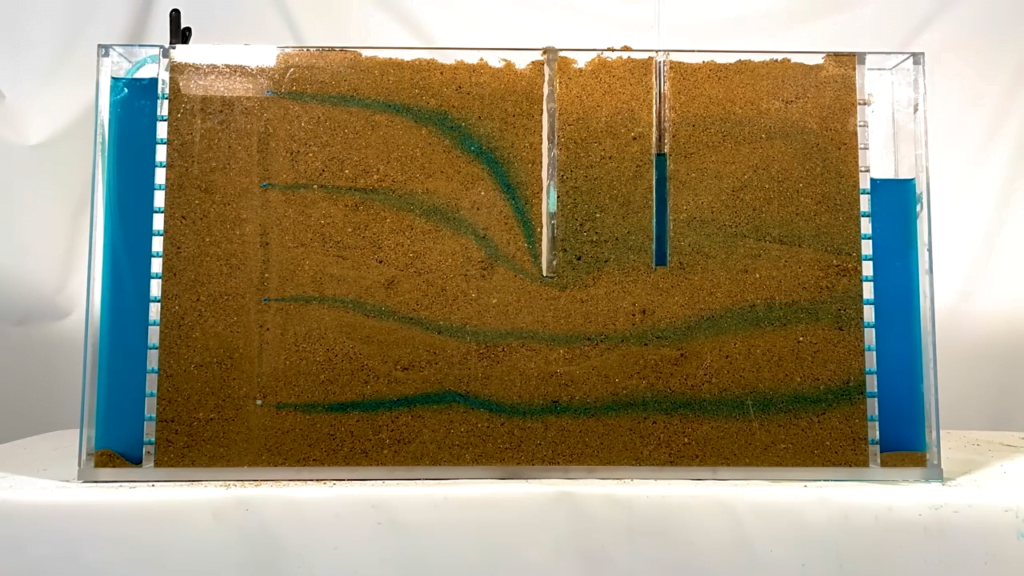

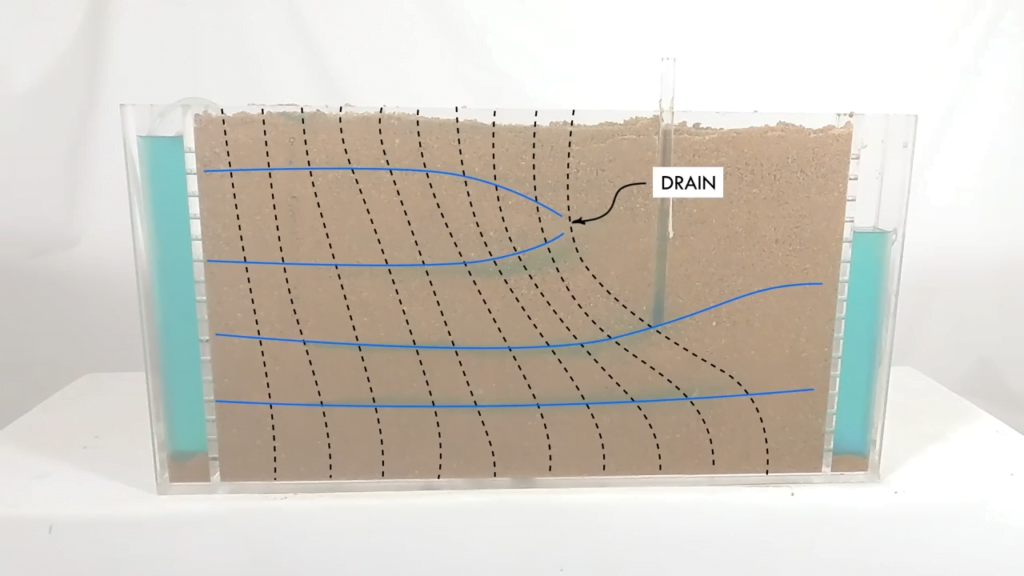

Groundwater-Structure Interactions

Groundwater can sometimes wind up in unexpected places, given the way it interacts with subsurface structures. In this Practical Engineering video, Grady discusses the paths that groundwater takes around structures and how civil engineers account for groundwater-related forces on dams and other buildings. As always, he illustrates with excellent model demos, allowing viewers to see groundwater interactions for themselves. (Image and video credit: Practical Engineering)

Kugel Fountains

At science museums and tourist attractions around the world, visitors can spin the multi-tonne spheres of kugel fountains with the brush of their hand. The secret of the sphere’s mobility is aquaplaning – the same phenomenon that can cause cars to lose traction in wet conditions. In these fountains, the massive sphere sits in a precisely-shaped cup, with their surfaces separated by a thin layer of water. The entire system acts like a hydrostatic bearing, which allows the sphere to move freely. But even a relatively small disruption can destroy the effect, as happened to the Science Museum of Virginia’s original Grand Kugel after it cracked. (Image credit: E. Roberts; via Atlas Obscura; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

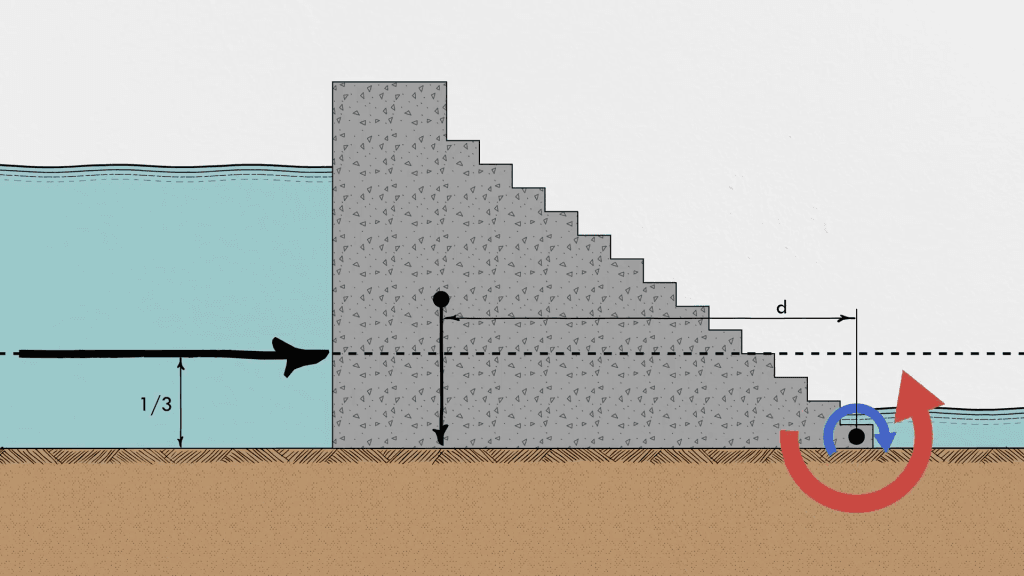

Dam Failure

In a recent video, Practical Engineering tackles an important and often-overlooked challenge in civil engineering: dam failure. At its simplest, a levee or dam is a wall built to hold back water, and the higher that water is, the greater the pressure at its base. That pressure can drive water to seep between the grains of soil beneath the dam. As you can see in the demo below, seeping water can take a curving path through the soil beneath a dam in order to get to the other side. When too much water makes it into the soil, it pushes grains apart and makes them slip easily; this is known as liquefaction. As the name suggests, the sediment begins behaving like a fluid, quickly leading to a complete failure of the dam as its foundation flows away. With older infrastructure and increased flooding from extreme weather events, this is a serious problem facing many communities. (Video and image credit: Practical Engineering)

Pascal’s Barrel Follow-Up

Pascal’s Law tells us that pressure in a fluid depends on the height and density of the fluid. This is something that you’ve experienced firsthand if you’ve ever tried to dive in deep water. The deeper into the water you swim, the greater the pressure you feel, especially in your ears. Go deep enough and the pressure difference between your inner ear and the water becomes outright painful.

In the video demonstration above, you’ll see how a tall, thin tube containing only 1 liter of water is able to shatter a 50-liter container of water. Not only does this show just how powerful height is in creating pressure in a fluid, but it shows how a fluid can be used to transmit pressure over a distance – one of the fundamental principles of hydraulics! (Video credit: K. Visnjic et al.; submitted by Frederik B.)

Reader @hoosierfordman77 writes:

“They’re pressurizing the line by using a syringe sealed to the tube. Of course, the volume of water in the tube added to this. But it was not the only source of pressure. Also explaining that pressure only has one vector as in the illustration using Hoover Dam is preposterous. Sir [sic] later stated correctly that pressure is evenly distributed through the inside of a container. If her demonstration was correct then the pressure of the water in lake Meade is not proportional to the volume of the lake…only proportional to its depth. Now I’ve not done testing but I do not believe a 100,000 acre lake that’s 1 foot deep would be held back by the walls of a kiddie pool that routinely handle that depth.” (emphasis added)

Hi, hoosierfordman77, thanks for your comment! It does seem counter-intuitive that pressure in a reservoir is proportional to depth, not volume, but it is correct. If you go swimming 1 meter below the water surface, the pressure you experience is the same whether you’re in a backyard pool or the Gulf of Mexico. And, yes, a 100,000 acre lake that’s 1 foot deep has a static pressure that could be withstood by a kiddie pool.

Now engineers don’t build it that way for a couple of reasons. 1) Pascal’s Law only describes hydrostatic forces – that is, the force experienced when the water is motionless. In reality, a dam would need to withstand not only the hydrostatic forces caused by the water’s depth but also any forces exerted when the water moves due to wind action, temperature differences, etc. And 2) after evaluating all of the expected forces a structure will endure, engineers add a factor of safety to make the structure strong enough to withstand forces above and beyond what is expected in ordinary or extraordinary operation.

As for the syringe, it only adds additional pressure to the line if they do not allow a gap for air in the line to escape. That can be a bit of a challenge, as they acknowledge in the video when they discuss the effects of air bubbles in the line. However, there is every indication that they were aware of this potential in their demonstration and did everything they could to ensure that it was not affecting the result. The fact remains, however, that extra pressure in the line is unnecessary – the 1 liter of water’s depth alone will shatter that container.

Pascal’s Barrel

Pascal’s Law tells us that pressure in a fluid depends on the height and density of the fluid. This is something that you’ve experienced firsthand if you’ve ever tried to dive in deep water. The deeper into the water you swim, the greater the pressure you feel, especially in your ears. Go deep enough and the pressure difference between your inner ear and the water becomes outright painful.

In the video demonstration above, you’ll see how a tall, thin tube containing only 1 liter of water is able to shatter a 50-liter container of water. Not only does this show just how powerful height is in creating pressure in a fluid, but it shows how a fluid can be used to transmit pressure over a distance – one of the fundamental principles of hydraulics! (Video credit: K. Visnjic et al.; submitted by Frederik B.)

The Pythagorean Cup

According to legend, Pythagoras invented a cup to prevent his students from drinking too greedily. If they overfilled the cup, it would immediately drain out all the fluid. The trick works thanks to a U-shaped tube in the center of the cup. As long as the liquid level is below the highest point in the U-tube, only the entrance side of the tube will be filled. As soon as the liquid level in the cup is higher, the weight of all that fluid forces liquid up and around the bend. This kicks off a siphoning effect that pulls all the fluid out. Coincidentally, this is the same way that toilet flushing works! Pulling the handle releases extra water into the bowl that raises the fluid level higher than the highest point in a U-bend. That establishes a siphon, which (provided nothing has clogged the pipe), empties the toilet bowl. (Video credit: Periodic Videos)

Crash Course Hydrostatics

Crash Course Physics has just put out an episode on fluids at rest (a.k.a. hydrostatics). For those who are unfamiliar, Crash Course is an educational YouTube channel that offers fun, instructional videos on a large and ever-growing array of topics. In this video, they tackle a lot of important basics for fluids, including the principles behind hydraulics, how to measure pressure, and how buoyancy works. It’s pretty densely packed, and, if you’re learning the concepts for the first time, you’ll probably pause and rewatch some segments, but even if you’re familiar with the topics, it’s a nice refresher. (Video credit: Crash Course Physics)

Perpetual Motion?

In the 17th century, scientist Robert Boyle proposed a perpetual motion machine consisting of a self-filling flask. The concept was that capillary action, which creates the meniscus of liquid seen in containers and is responsible for the flow of water from a tree’s roots upward against gravity, would allow the thin side of the flask to draw fluid up and refill the cup side. In reality, this is not possible because surface tension will hold it in a droplet at the end of the tube rather than letting it fall. In the video above, the hydrostatic equation is used to suggest that the device works with carbonated beverages (it doesn’t; the video’s apparatus has a hidden pump) because the weight of the liquid is much greater than that of the foam. Of course, the hydrostatic equation doesn’t apply to a flowing liquid! The closest one can come to the hypothetical perpetual fluid motion suggested by Boyle is the superfluid fountain, which flows without viscosity and can continue indefinitely so long as the superfluid state is maintained. (Video credit: Visual Education Project; submission by zible)