Streams of blue and yellow braid across Iceland’s volcanic landscape in this award-winning photo from Miki Spitzer. Glacial water shows an icy blue and sediments glisten in gold. Together, their interplay creates an arresting delta viewed from above. (Image credit: M. Spitzer; via WNPA)

Tag: glacier

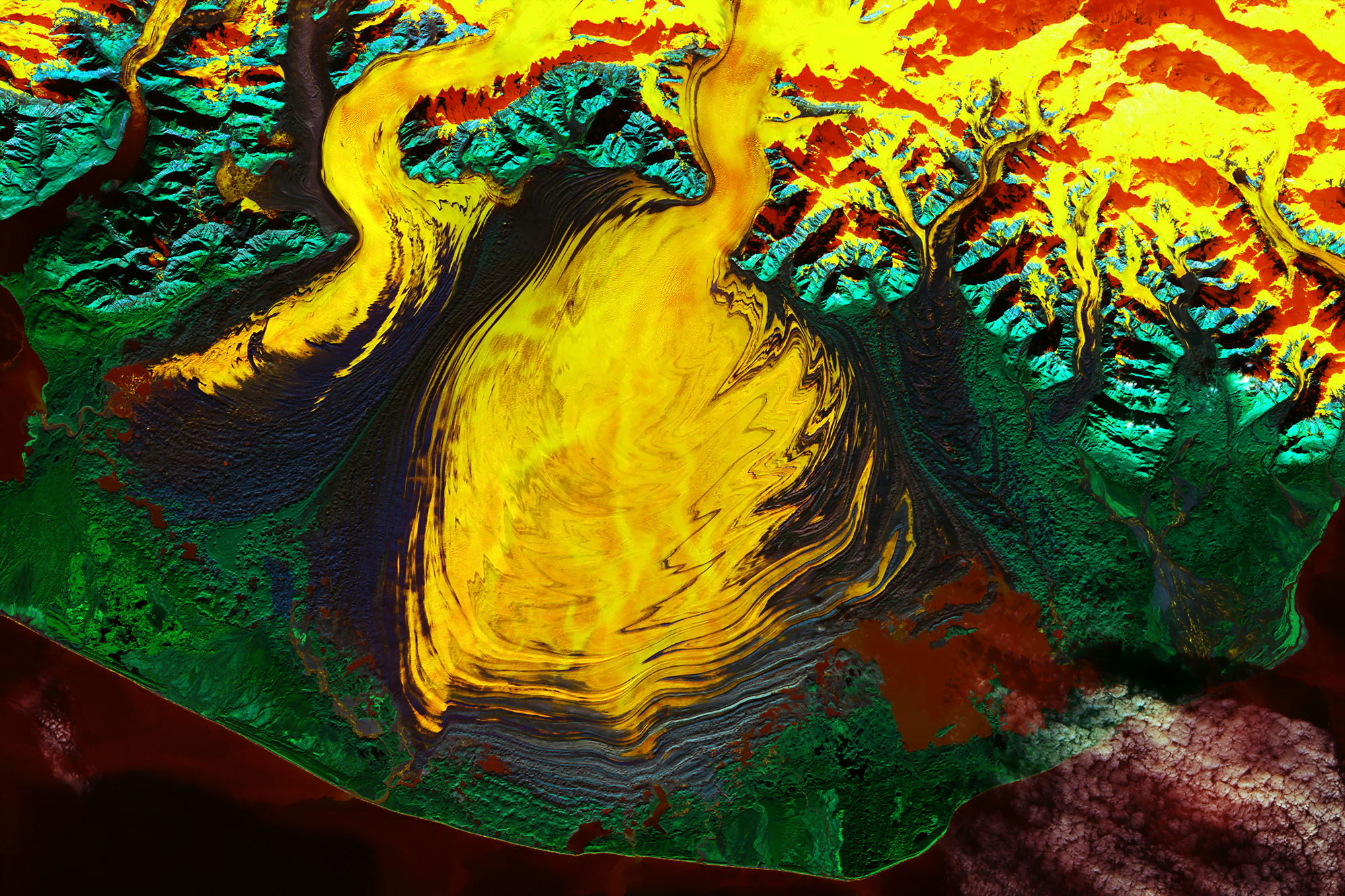

Fire in Ice

This false-color satellite image of Malaspina Glacier (Sít’ Tlein) is a riot of color. Composed of coastal/aerosol, near infrared, and shortwave infrared bands from Landsat 9, the colors highlight features otherwise hard to identify. Watery features appear in reds, oranges, and yellows; vegetation is green and rock appears in blue. The glacier covers more than 4000 square kilometers, an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. The dark lines atop the glacier are moraines, where rock, soil, and other debris has been scraped up along the glacier’s edge. Over time, changes in the glacier’s velocity cause the moraines to fold and shear, creating the zigzag pattern seen here. (Image credit: W. Liang; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Melting Ice Cap

This award-winning photo by Thomas Vijayan shows waterfalls of ice melt off the Austfonna ice cap. The third-largest glacier in Europe, Austfonna is located in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago. Like other glaciers, it sees rising temperatures and increased melting due to climate change. Vijayan highlights that melting with his focus on the many waterfalls slicing through the ice. All that meltwater contributes to changes in local salinity as well as rising sea levels worldwide. (Image credit: T. Vijayan; via Nature TTL POTY)

Icelandic Glacial Caves

Expedition guide and photographer Ryan Newburn captures the ephemeral beauty of the glacial caves he explores in Iceland. These caves are in constant flux, thanks to the run and melt of water. The scalloped walls are a sign of this process of melting and dissolution. The icicles, too, hint at ongoing melting and refreezing. Caves can appear and disappear rapidly; they’re a dangerous environ, but Newburn freezes them in time, letting the rest of us experience a piece of their majesty. See more of his images on his Instagram. (Image credit: R. Newburn; via Colossal)

Summer Melt

A warm summer in 2022 has resulted in record melting on Svalbard. Located halfway between the Norwegian mainland and the North Pole, more than half of Svalbard is normally covered in ice. But with glaciers in retreat and firn — a surface layer of compressed porous snow — melting, pale blue ice is getting direct exposure to the sun and warm air temperatures. The result has been melting 3.5 times larger than the average melt between 1981 and 2010. Look closely and you’ll find deep blue meltwater ponds dotting the ice, too. The run-off of meltwater has likely carried extra sediment into the surrounding waters, accounting for some of the paler water colors along the coast. (Image credit: J. Stevens/USGS; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Martian Glaciers

On Earth, glaciers slide on lubricating layers of water, leaving complex landscapes like fjords and drumlins in their wake. Mars — though once home to enormous ice masses — lacks those geological features. Scientists assumed, therefore, that Martian ice stayed frozen and unmoving. But a new study demonstrates that is not the case.

Researchers used computational modeling to simulate two identical glaciers: one under Earth-like conditions and one under the lower gravity of Mars. They found that Martian glaciers did indeed move, but Mars’s lower gravity, combined with better water drainage beneath the ice, meant that they moved exceedingly slowly. Martian glaciers did erode the landscape but into different features than on Earth. Instead of forming moraines and drumlins, a large Martian glacier would instead carve channels and eskar ridges, geological features found on Mars today. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-CalTech/Uni. of Arizona; research credit: A. Grau Galofre et al.; via AGU; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Columbia Glacier’s Retreat

In southeastern Alaska, the Columbia Glacier once stretched as far as Heather Island in Prince William Sound. After a long period of stability, the glacier began retreating in 1980 and currently sits more than 15 miles from its previous extent. This video explores the glacier’s evolution through false-color satellite imagery, which allows researchers to distinguish the glacier from sea ice, open water, exposed rocks, and nearby vegetation. Though rapid overall, the glacier’s retreat takes place in fits and starts, due to a combination of influences including climate change, sea and ice interactions, and the effects of local topography. (Video and image credit: NASA Earth Observatory)

False-color animation showing the retreat of Alaska’s Columbia Glacier since 1980.

Filming a Calving Glacier

The San Rafael Glacier, one of the fastest calving glaciers in the world, sits above a fjord in Patagonia. About 10 – 25 meters of the glacier is lost to calving every day. Here, filmmakers take you behind-the-scenes to show what it takes to film in such a remote, unpredictable, and dangerous environment. (Image and video credit: BBC Earth)

Recession at Taku Glacier

A glacier’s snowline marks the location where the amount of summer melting and accumulated snowmass are equal. If, over the course of a season, a glacier experiences more snowfall than melting, its snowline will advance. If melting outweighs accumulation, then the snowline will retreat to higher altitudes. Tracking the snowline gives scientists important data about how the glacier is changing.

And that change is typically slow. When glaciers stop advancing, their snowlines can remain unmoving for decades. Or, at least, they used to. In recent years, Alaska’s Taku Glacier was one of the only alpine glaciers holding out against the warming Arctic. Its slow advance stopped in 2013–the left image shows Taku in 2014–and researchers hoped the massive glacier would maintain its mass for a few decades at least. Instead, the glacier was retreating by 2018 and doing so with the highest mass loss ever recorded at the glacier. The 2019 image on the right shows the glacier’s visible losses.

For such a massive glacier–the largest in Juneau Icefield at nearly 1.5 km thick–to reverse fortunes so quickly is disturbing and serves as yet more evidence of climate change overriding natural cycles of advance and retreat. (Image credit: L. Dauphin/USGS; via NASA Earth Observatory)

As Ice Flows

The movement of glaciers is driven by gravity. The immense weight of the ice causes it to both slide downhill and deform – or creep. As glacier melting speeds up, scientists have debated how glacier flow will respond: will the loss of ice cause the glaciers to move more slowly since they have less mass, or will the increase in meltwater help lubricate the underside of glaciers and make them flow even faster?

By analyzing satellite image data of Asian glaciers collected between 1985 and 2017, researchers are finally answering that question. Their research shows that these glaciers are slowing down as they lose mass and speeding up as they gain mass. Nearly all – 94% – of the flow changes they observed can be accounted for solely from ice thickness and slope. This is valuable information as scientists continue to monitor and predict the changes we must expect as the world continues to warm. (Image credit: J. Stevens; research credit: A. Dehecq et al.; via NASA Earth Observatory)