When instabilities exist in laminar flow, they do not always lead immediately to turbulence. In this video, a viscous fluid fills the space between two concentric cylinders. As the inner cylinder rotates, a linear velocity profile (as viewed from above) forms; this is known as Taylor-Couette flow. If any tiny perturbations are added to that linear profile–say there is a nick in the surface of one of the cylinders–the flow will develop an instability. In this type of flow, an exchange of stabilities will occur. Rather than transitioning to turbulence, the fluid develops a stable secondary flow–the toroidal vortex highlighted by the dye in the video. If the rotation rate is increased further other instabilities will develop.

Tag: flow visualization

Aircraft Contrails

[original media no longer available]

Under the right atmospheric conditions, condensation can form, even at low speeds, as moist air is accelerated over airplane wings. This acceleration causes a local drop in pressure and temperature, which can cause water vapor in the air to condense. The condensation can sometimes get pulled into the wingtip vortices shed off of the wings, tail, and ailerons of an aircraft, as in the video above, making the aerodynamics of the airplane visible to the naked eye.

Shuttlecock Flow Viz

The flow around a shuttlecock is visualized in a water channel using fluorescent dye illuminated by laser light ultraviolet LEDs. Note the recirculation zone on the upper shoulder. Experimenters can match flow characteristics in water to that in air by matching the Reynolds numbers. (Photo credit: Rob Bulmahn)

Updated, thanks to information from the photographer. Thanks!

Flow Viz of a Locust

Smoke visualization in a wind tunnel reveals the airflow over a flying locust. Researchers are unraveling the aerodynamics of insect flight in order to produce better Micro Air Vehicles (MAVs) and miniature flying robots. #

Smoke Visualization on an F-16

Flow around an F-16XL Scamp model is visualized using smoke illuminated by laser sheets. Lasers are common equipment in fluids laboratories; they’re useful for flow visualization and for many velocimetry techniques.

Aerodynamics with Bill Nye and Samuel L. Jackson

Bill Nye, Samuel Jackson, golf balls, Reynolds number, dimples, and boundary layers. It doesn’t get much better than this. – Khristopher O (submitter)

It definitely beats Jackson’s other foray into aerodynamics! The dimples on a golf ball cause turbulent boundary layers, which actually decrease drag on the ball and make it fly farther. Why bluff bodies experience a reduction in drag as speed (and thus Reynolds number) increases was a matter of great confusion for fluid mechanicians early in the twentieth century, but it’s not too hard to see why it happens with some flow visualization.

On the top sphere, the laminar boundary layer separates from the sphere just past its shoulder. This results in a pressure loss on the backside of the sphere and, thus, an increase in drag. On the bottom sphere, a trip-wire placed just before the shoulder causes a turbulent boundary layer, which separates from the sphere farther along the backside. This late separation results in a thinner wake and a smaller pressure loss behind the sphere, thereby reducing the overall drag when compared to the laminar case. (Photo credit: An Album of Fluid Motion)

Shock Waves

Flow visualization really can be considered a form of art. Though we fluid mechanicians are looking for physics, we’re quite aware of the beauty of what we study. The clips in this video mostly show transient shockwave behavior, including lots of shock reflection and even a few instabilities. It’s unclear what the speeds are, aside from faster than sound; the medium is air.

Flow Visualization

[original media no longer available]

This video gives a neat introduction to some common and uncommon techniques used to visualize fluid flows.

Wake of a Rising Sphere

This flow visualization shows the wake left by a freely rising sphere. Observations of rising and falling spheres date at least back to Newton, who observed that the inflated hog bladders he used “did not always fall straight down, but sometimes flew about and oscillated to and fro while falling”. That vibration is caused by the vortices seen here in the wake. There are actually four vortices shed per oscillation cycle–two primary vortices (marked P) and two secondary vortices (marked S). #

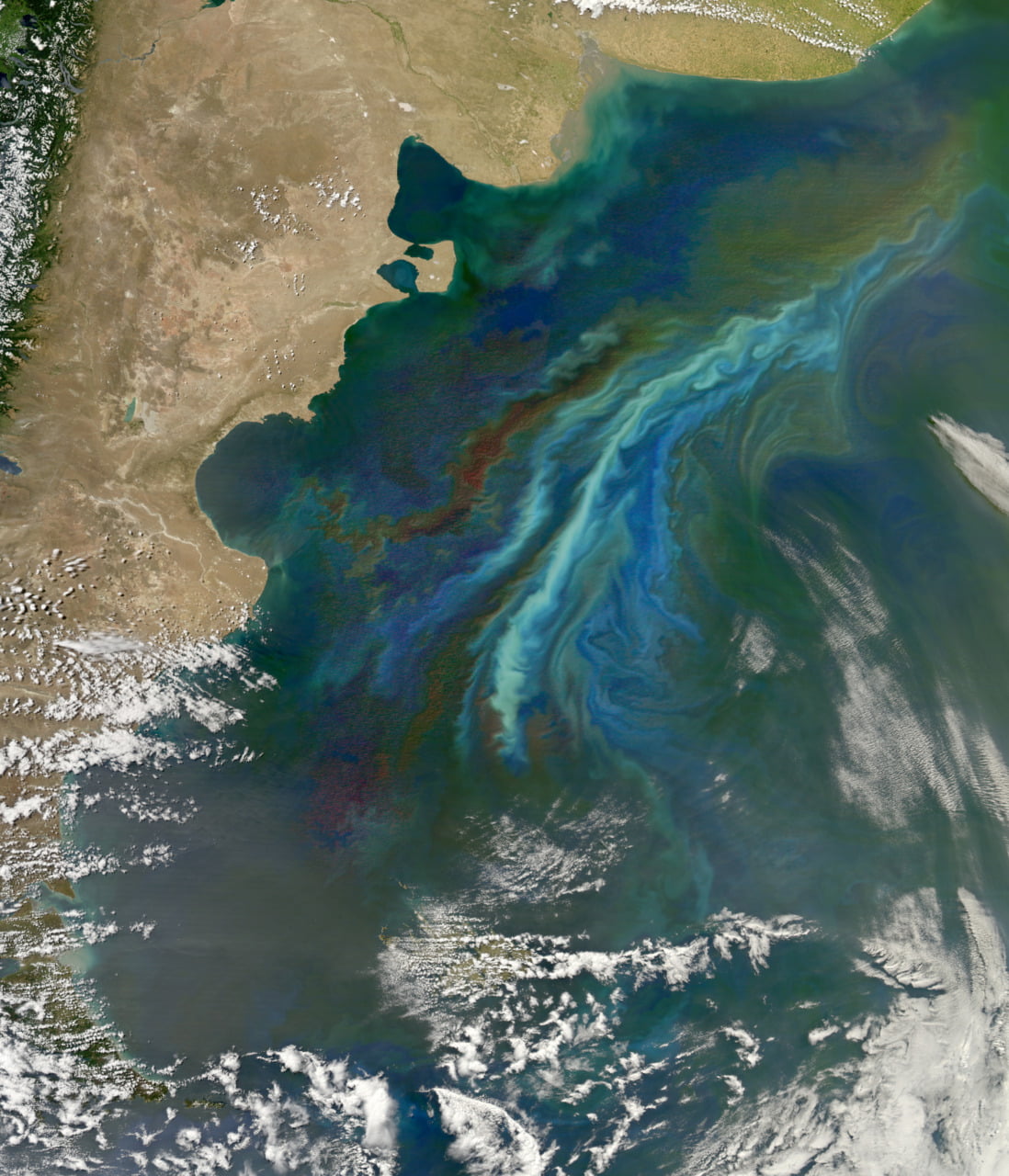

Turbulent Phytoplankton Eddies

Where warm and cold ocean currents collide, turbulent eddies form and pull up valuable nutrients from the ocean floor. Massive phytoplankton blooms ensue, effectively providing natural flow visualization for the process. #