It didn’t take long for an aerodynamic controversy to crop up in this year’s Tour de France. At the 14km individual time trial, riders from Team Sky wore custom Castelli skinsuits with integrated dot-like patterns on their upper arms (shown above). By the next day, a sports scientist with a competing team cried foul play, claiming that these fabrics could have given Team Sky as much as 25 seconds’ advantage over other riders. The Sky team finished with 4 out of the top 10 places on the time trial, and their leader, three-time Tour winner Chris Froome, finished some 35 seconds ahead of his expected competitors for the yellow jersey.

Vortex generators explained

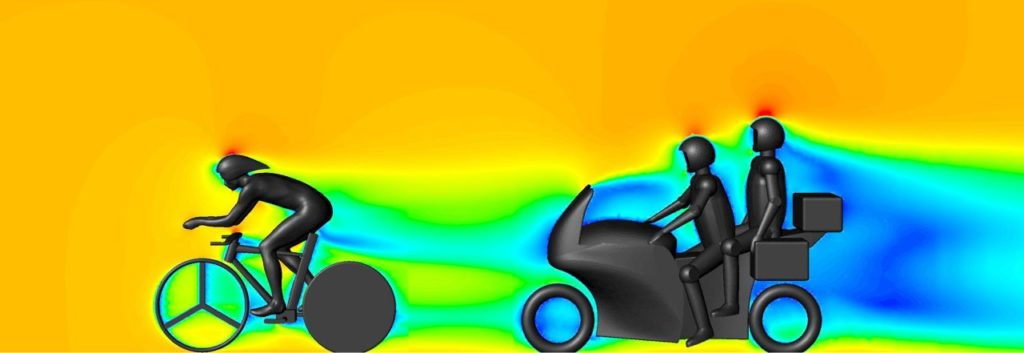

So how could a few dots make a measurable difference? These protrusions are vortex generators meant to modify flow around a cyclist. Humans are not aerodynamic and what typically happens when air flows over a cyclist’s arms is shown in the flow visualization above: the air follows the curve of the arm part way, then it separates from the body, leaving a region of recirculation that increases drag. Vortex generators can help prevent or delay that drag-inducing flow separation by adding extra energy and turbulence to the air near the arm’s surface. Because turbulent boundary layers can follow a curve longer before separating, this helps reduce the drag by reducing the recirculation zone.

About that time savings

Aerodynamically speaking, those vortex generators can make a difference, but the question is, how much? In his complaint, Grappe cites a 2016 paper by L. Brownlie et al. that wind-tunnel tested different vortex generator patterns for use in running apparel. The speeds tested included those relevant to cycling. The specific numbers Grappe quotes aren’t directly relevant, however:

As noted above, race garments that contain VG provide reductions in Fd of between 3.7 and 6.8% compared to equivalent

advanced race apparel developed for the 2012 London Olympics which in turn provided substantially lower drag than

conventional race apparel.

the effectiveness of 5, 10 and 15 cm wide strips of VG applied to each flank of a sleeveless singlet revealed that the 5 cm wide

strips provided between 3.1 and 7.1% less Fd than the 10 cm wide strips and between 1.9 and 4.3% less Fd than the 15 cm wide

strips.

Here Brownlie et al. are specifically describing the savings for running apparel, which uses vortex generators in very different places than you would on a cyclist. Note the second quote even refers to a sleeveless singlet, so the vortex generators measured are definitely not in the same place as these skinsuits!

The bottom line

I fully expect that vortex generators give a marginal aerodynamic edge, which is why Sky and other teams have already been using them in competition. But I hesitate to declare that the savings is as high as 5-7%, and I have no way to verify Grappe’s subsequent claims that this translates to 18-25 seconds in the time trial. Those are numbers he gives without citing what model is being used to translate drag gains into time.

In the end, what is needed is clarification of the rules. As they stand, one rule seems to allow the skinsuits because the vortex generators are integrated into the fabric, whereas another states clothing is forbidden “to influence the performances of a rider such as reducing air resistance”. Those two stances seems contradictory, and, for now, the race officials’ verdict to allow the suits stands.

If you want to learn more about aerodynamics and cycling, be sure to check out my latest FYFD video. (Image credits: B. Tessier/Reuters; Getty Images; L. Brownlie et al. 2009; h/t to W. Küper)