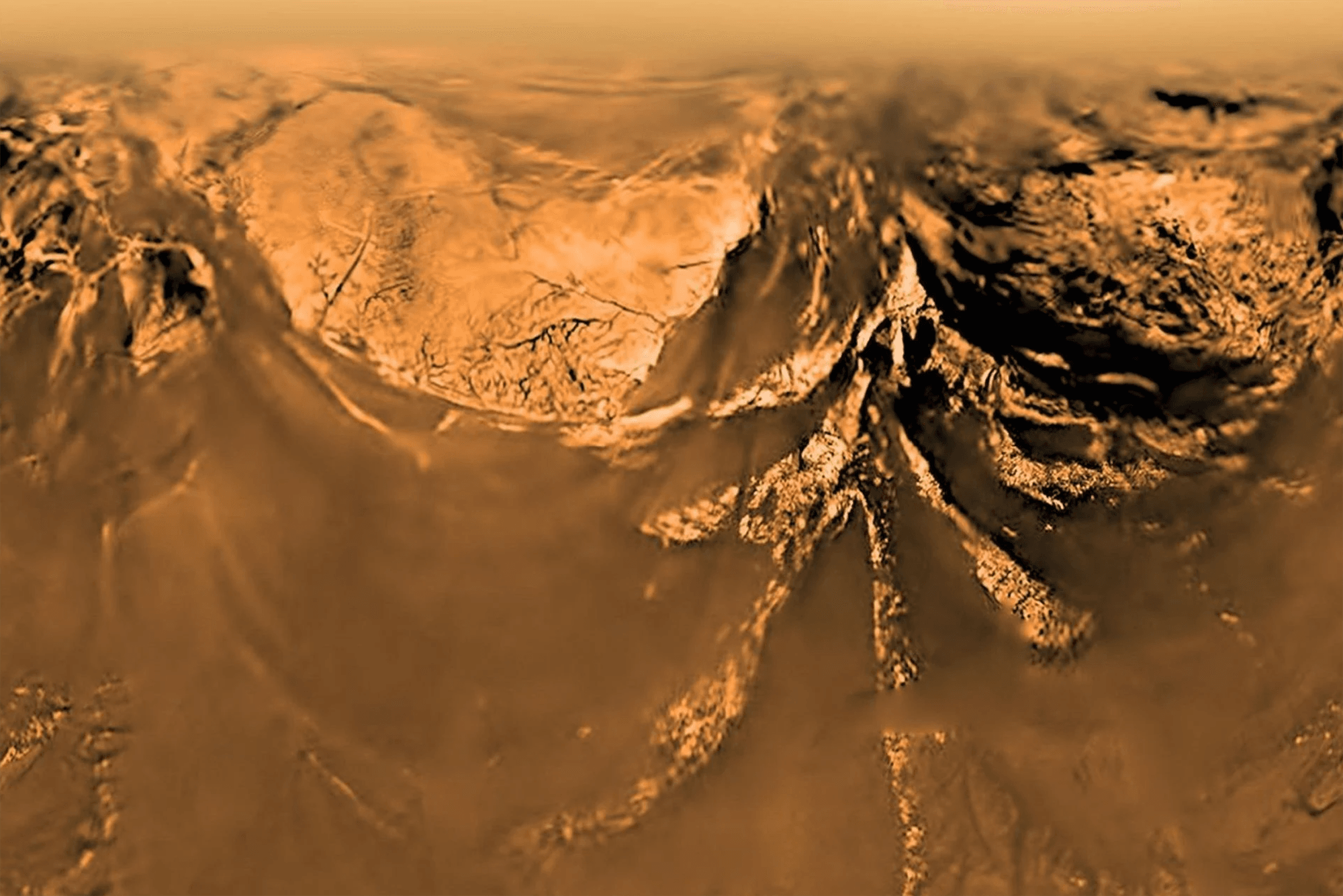

Scientists are still debating exactly what shifts nature from chemical and physical reactions to living cells. But vesicles — small membrane-bound pockets of fluid carrying critical molecules — are a commonly cited ingredient. Vesicles help cluster important organic molecules together, increasing their chances of combining in the ways needed for life. Now scientists are suggesting that Titan, Saturn’s moon, could form vesicles of its own.

On Earth, molecules known as amphiphiles feature a hydrophilic (water-loving) end and a hydrophobic (water-fearing) one. When dispersed in water, amphiphiles crowd at the surface, placing their hydrophilic end in the water and their hydrophobic end outward toward the air. On Titan, the Cassini mission revealed organic nitrile molecules that behave similarly with methane rather than water.

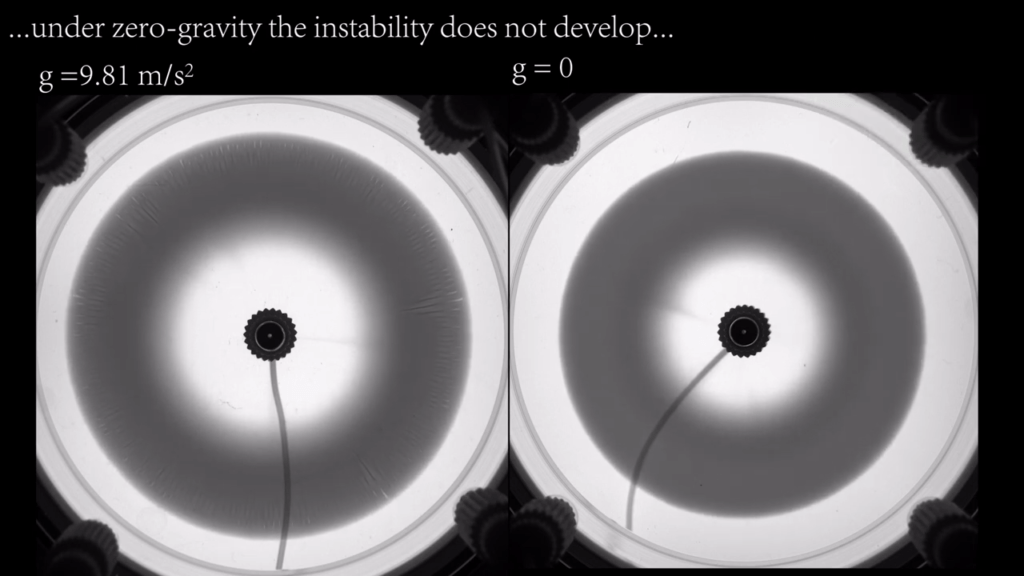

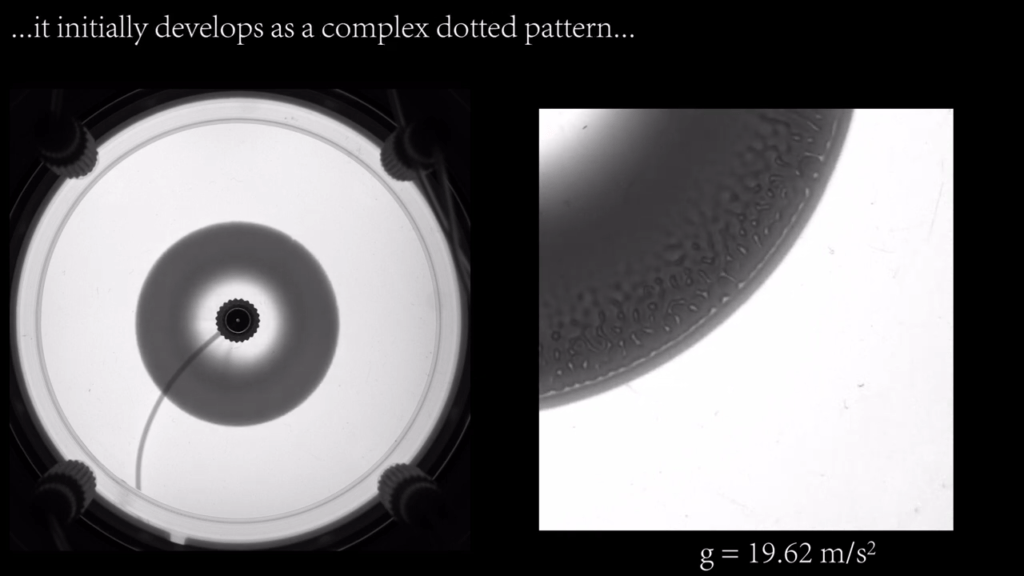

Their two-sided structure means that these molecules — like Earth’s amphiphiles — will gather at the surface of Titan’s liquids. When methane rain falls on the Titan’s seas, the impact creates aerosol droplets that slowly settle back to the liquid surface. When that happens, the droplet’s molecular monolayer and the lake’s monolayer meet, enclosing the droplet’s contents in a double-layer of molecules that prevent contact between the droplet and the lake.

Within that newly-formed vesicle, all kinds of molecules can bump shoulders, creating new opportunities for complex chemistry. (Image credit: Titan – ESA/NASA/JPL/University of Arizona, illustration – C. Mayer and C. Nixon; research credit: C. Mayer and C. Nixon; via Gizmodo)