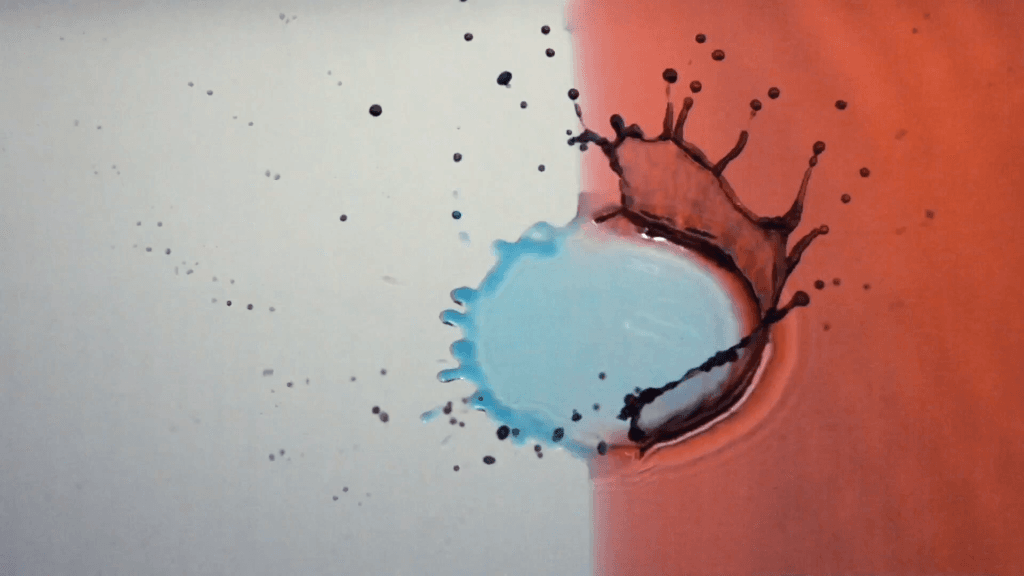

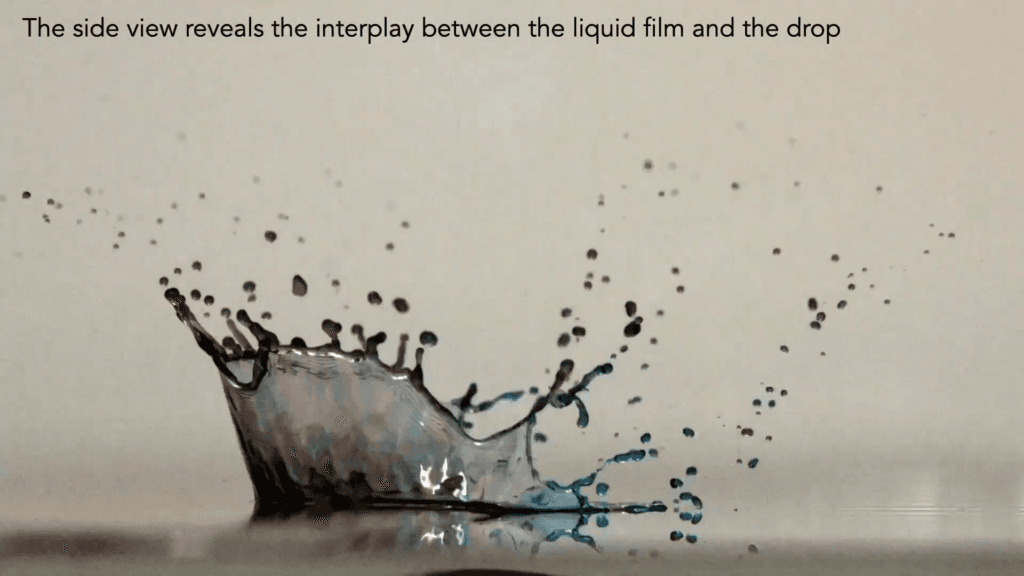

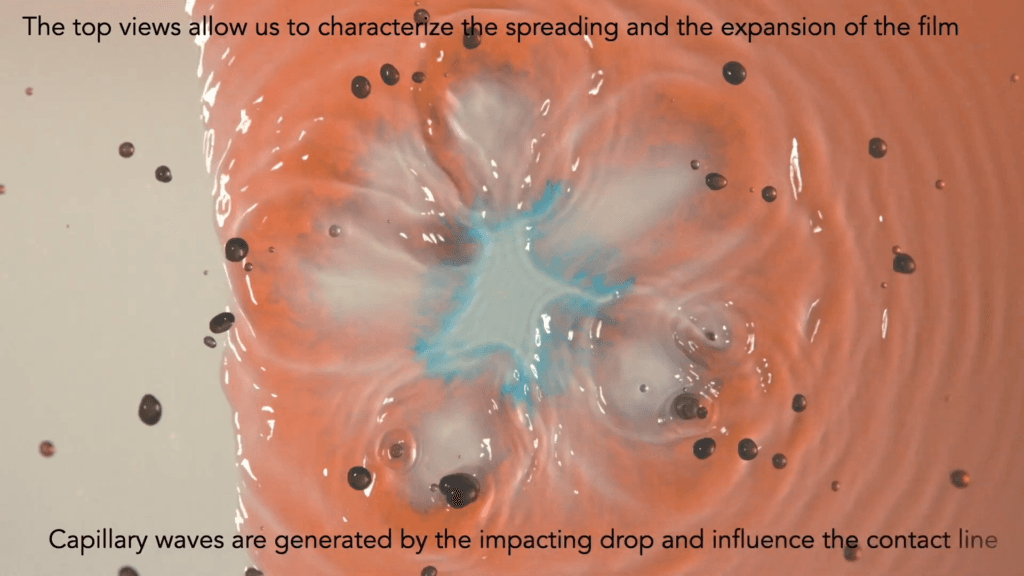

Drops impacting a dry hydrophilic surface flatten into a film. Drops that impact a wet film throw up a crown-shaped splash. But what happens when a drop hits the edge of a wet surface? That’s the situation explored in this video, where blue-dyed drops interact with a red-dyed film. From every angle, the impact is complex — sending up partial crown splashes, generating capillary waves that shift the contact line, and chaotically mixing the drop and film’s liquids. (Video and image credit: A. Sauret et al.)

Tag: wetting

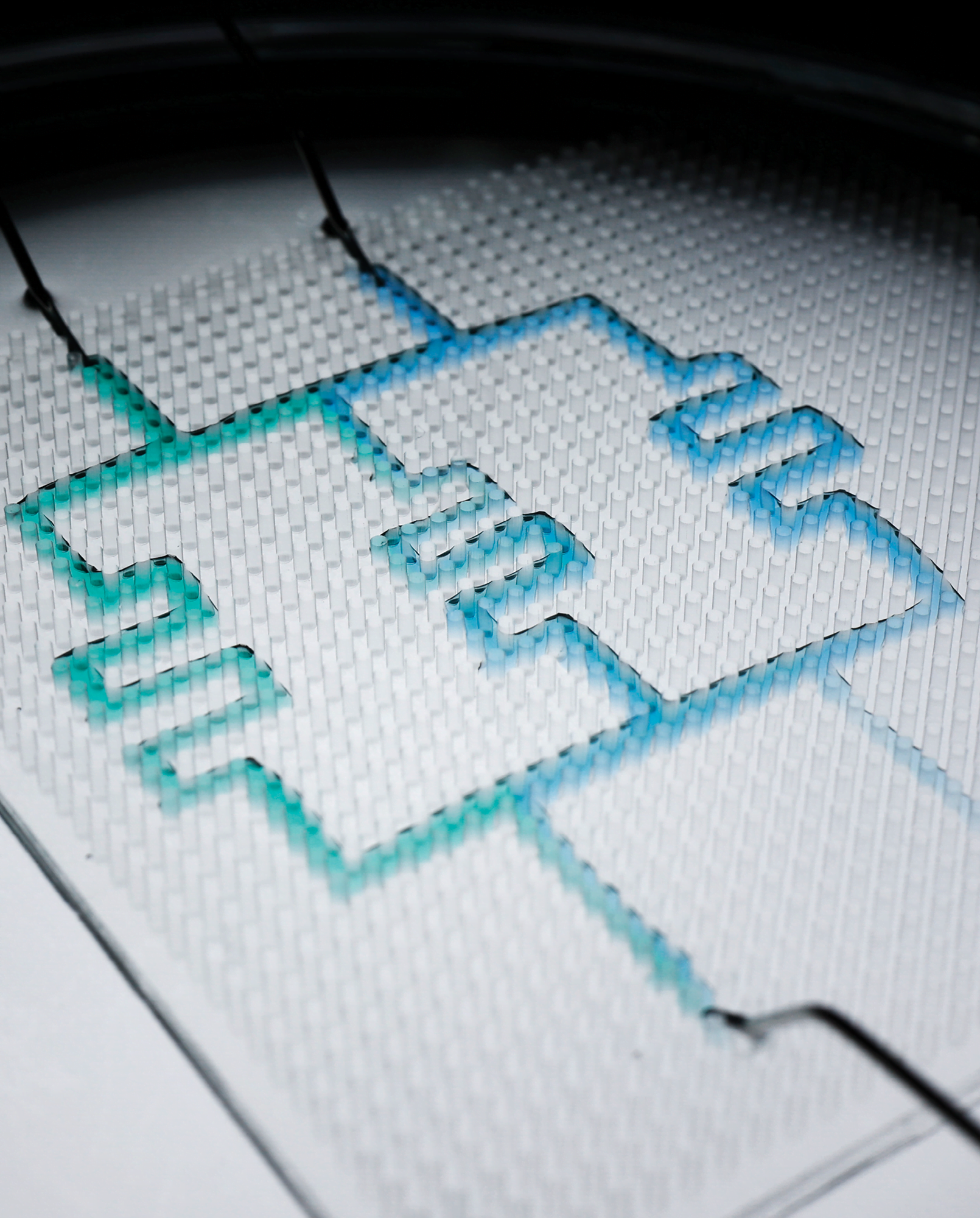

Making Reconfigurable Liquid Circuits

Microfluidic circuits are key to “labs on a chip” used in medical diagnostics, inkjet printing, and basic research. Typically, channels in these circuits are printed or etched onto solid surfaces, making it difficult to reconfigure them. A group in China developed an alternative design, inspired by reconfigurable toys like Lego blocks. Their set-up, shown above, uses a pillared surface immersed in oil. To create the channels, they pipette water — one droplet at a time — into the space between pillars. The combination of oil and pillars traps the drop. With multiple drops linked together, they get channels, like the ones above that mix two fluids. When the time comes to reconfigure the channels, they just pipette the water out and cut the channel with a sheet of coated paper. (Image and research credit: Y. Zeng et al.; via Physics Today)

Stopping The Drop

When a droplet falls on a mesh surface, some of the liquid can burst through the holes (top row). But subsequent drops have a harder time penetrating the prewetted mesh. After a few drops have impacted (rows 2-3), the wetted mesh can completely suppress penetration (rows 4-5). The authors found that the taller drops sitting atop the mesh were better at stopping penetration from an incoming drop. (Image and research credit: L. Xu et al.)

Spreading By Island

How does a droplet sinking through an immiscible liquid settle onto a surface? Conventional wisdom suggests that the settling drop will slowly squeeze the ambient fluid film out of the way, form a liquid bridge to the solid beneath, and spread onto the surface. But for some droplets, that’s not how it goes.

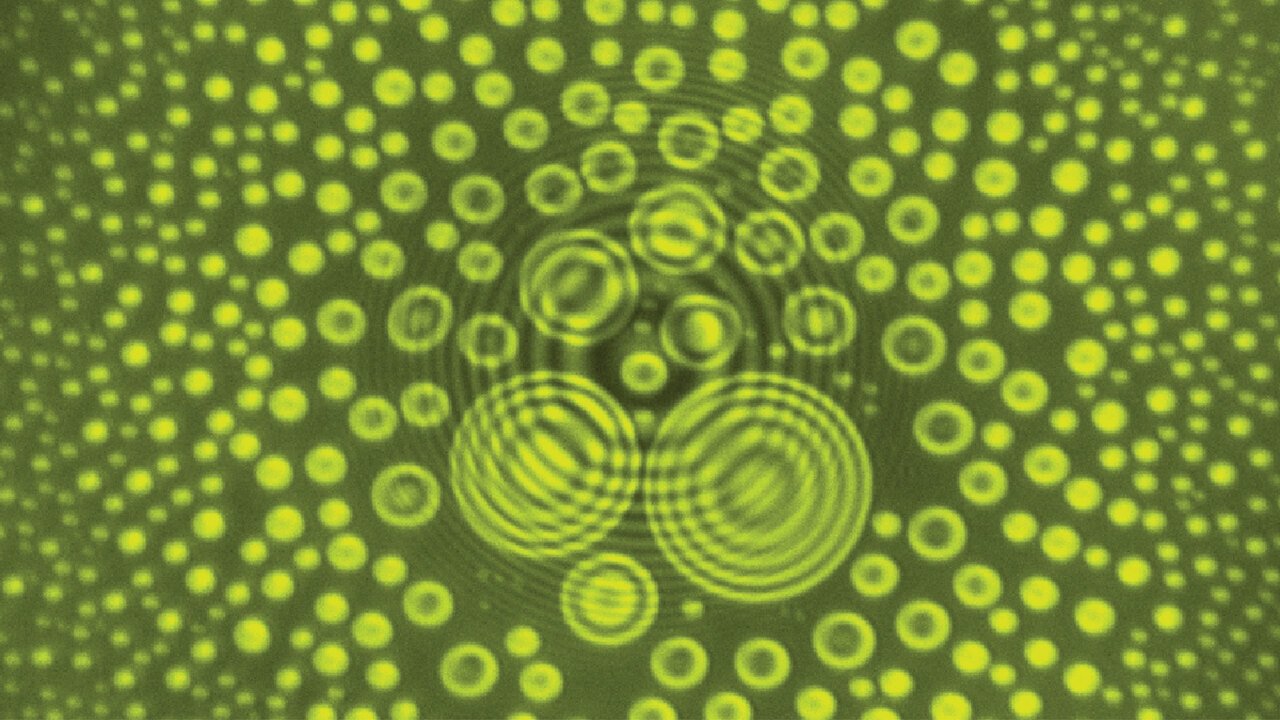

While watching a glycerol droplet settle through silicone oil, researchers discovered a new mechanism for wetting. Initially, the silicone oil drained from beneath the drop, as expected. But then the thinning of the film stalled. Tiny bright spots (above) appeared beneath the light and dark interference fringes of the parent drop. These are spots of glycerol, formed when material from the main drop dissolved into the oil and then nucleated onto the solid surface below. Over time, the island-like spots of glycerol grew. Eventually one grew large enough to coalesce with its parent drop (below), causing the glycerol to quickly spread over the solid surface!

Islands of liquid (darker rings) grow beneath a parent drop (brighter rings) until reaching a size where they coalesce, causing the interference fringes to disappear. The key to this phenomenon seems to be that immiscibility isn’t perfect. Even trace amounts of solubility between the drop and surrounding fluid are enough to allow these islands to form. And once formed, the islands will grow as long as the drop fluid and the solid surface are chemically attractive. (Image, research, and submission credit: S. Borkar and A. Ramachandran; see also Nature Behind the Paper)

Reducing the Force of Water Entry

As anyone who’s jumped off the high board can tell you, hitting the water involves a lot of force. That’s because any solid object entering the water has to accelerate water out of its way. This is why gannets and other diving birds streamline themselves before entering the water. But even for non-streamlined objects, like a sphere, there are ways to reduce the force of impact.

This video explores three such techniques, all of which involve disturbing the water before the sphere enters. In the first, the sphere is dropped inside a jet of fluid. Since the jet is already forcing water down and aside when the sphere enters, the acceleration provided by the sphere is less and so is the force it experiences.

The second and third techniques both rely on dropping a solid object ahead of the one we care about. In the second case, a smaller sphere breaks the surface ahead of the larger one, allowing the big sphere to hit a cavity rather than an undisturbed surface. Like with the jet, the first sphere’s entry has already accelerated fluid downward, so there’s less mass that the bigger sphere has to accelerate, thereby reducing its impact force.

In the third case, the first sphere is dropped well ahead of the second, creating an upward-moving Worthington jet that the second sphere hits. In this case, there’s water moving upward into the sphere, so how could this possibly reduce the force of entry? The key here is that the water of the jet wets the sphere before it enters the pool. Notice how very little air accompanies the second sphere compared to the first one. That’s because the second sphere is already wet. It’s also been slowed down by the jet so that it enters the water at a lower speed, all of which adds up to a lower force of entry. (Image and research credit: N. Speirs et al.)

Putting a Spin on Splashes

Researchers put a spin on splashing droplets with selective wetting. When a drop impacts on a water-repellent, superhydrophobic surface, it will spread circularly, then pull back together and rebound off the surface. That’s because the surface coating resists actually touching – or being wetted by – the water. But just as there are surface coatings that resist water, there are those that attract it.

Above, researchers have coated a surface so that it’s mostly superhydrophobic, but it also has narrow pinwheel-like arms that are hydrophilic. As the drop impacts, it spreads across the surface and then retracts. But where the hydrophilic arms are, the drop lingers. This creates the four lobes we see on the droplet, and the asymmetric retraction gives the drop angular momentum. As it leaves the surface, the spin continues. In some configurations, the researchers could make the drop spin at more than 7300 rpm. (Image and research credit: H. Li et al; via Science; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Staying Dry Underwater

Many insects are known to quest underwater, but few are as adept at it as the alkali fly. This species has taken common attributes among flies – being covered in tiny hairs and a waxy layer – and really upped the ante. Their extra hairiness and extra waxiness make them extremely difficult to get wet, even in the excessively salty and alkaline waters of California’s Mono Lake, which are enough to defeat all but algae, brine shrimp, bacteria, and alkali flies.

Staying dry is a challenge, but only one of many this insect tackles. The combination of hair and wax over the insect makes it superhydrophobic, coating it in a silvery layer of air as it crawls below the surface. All that air is buoyant, so to walk underwater, the fly has to exert forces up to 18 times its body weight just to keep from popping back up to the surface.

The shimmering bubble also helps the fly breathe. Insect respiratory systems use openings all over the exoskeleton to exchange oxygen with the ambient atmosphere via diffusion. While diffusion of oxygen does still happen underwater, it’s a much slower process there. The air sheath around the fly creates a large surface area for oxygen to diffuse, which helps counter the lower diffusion rate. Inside the sheath, the fly breathes as it normally does. (Image and research credit: F. van Breugel and M. Dickinson; via Gizmodo; submitted by @1307phaezr)

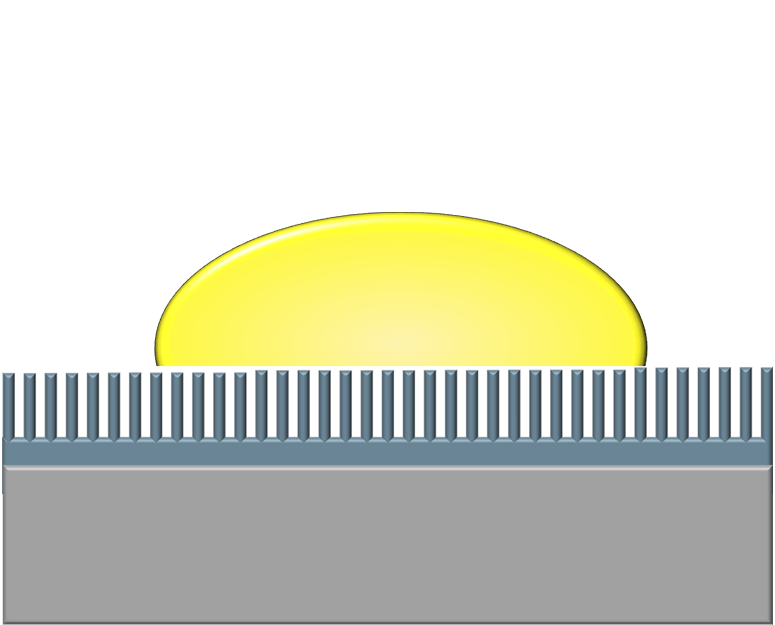

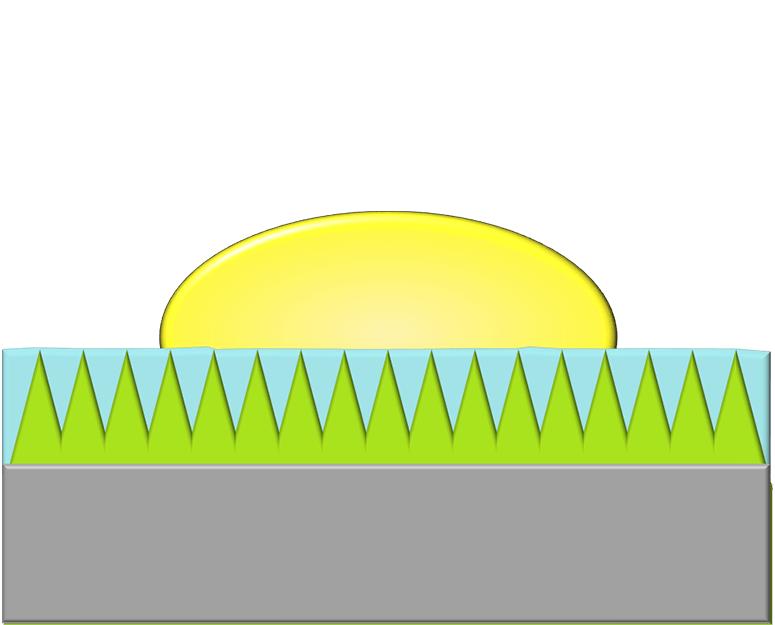

Easy Squeezing

Nearly everyone has struggled with the frustration of trying to get ketchup, toothpaste, or peanut butter out of a container. These fluids and fluid-like substances are notoriously difficult to budge because they prefer to wet and adhere to solid surfaces. One way to limit this adhesion is to use a superhydrophobic surface, like the one shown in the middle image. These surfaces use micro- and nanoscale roughness to trap air pockets underneath a liquid and reduce the amount of contact between the liquid and solid. But such surfaces are delicate and prone to failure. The slippery alternative offered by LiquiGlide is a liquid-impregnated surface, shown in the bottom image. Like a superhydrophobic surface, it consists of a textured solid but one that’s filled with a liquid lubricant that preferentially wets the solid. As a result, the liquid to be shed has little to no contact with the actual solid surface and therefore slides easily off! (Image credit: LiquiGlide, source; research credit: K. Varanasi et al.; suggested by cnsidero)

Rebounding Off Dry Ice

Droplet rebound is frequently associated with superhydrophobic surfaces but can also be generated by very large temperature differences. For very hot substrates, a thin layer of the drop vaporizes on contact via the Leidenfrost effect and helps a drop rebound by preventing it from wetting the surface. This video shows almost the opposite: a water droplet hitting solid carbon dioxide (-79 degrees C). Upon contact, the solid carbon dioxide sublimates, creating a thin layer of gas that separates the droplet from the surface. You can also see the vortex ring that accompanies the drop’s impact. Water vapor near the carbon dioxide surface has condensed into tiny airborne droplets that act as tracer particles that reveal the vortex’s formation and the rebounding droplet’s wake. (Video credit: C. Antonini et al.; Research paper)

Superhydrophobic Carbon Nanotubes

Carbon nanotubes form a superhydrophobic (super water repellent) surface that interacts with water droplets in interesting ways. The droplet is unable to wet the surface and thus the bounces along. When the impact velocities are too great for surface tension to hold the decelerating mass together, it breaks into many, smaller droplets that also bounce along the surface. # (via @JetForMe and @Vinnchan)