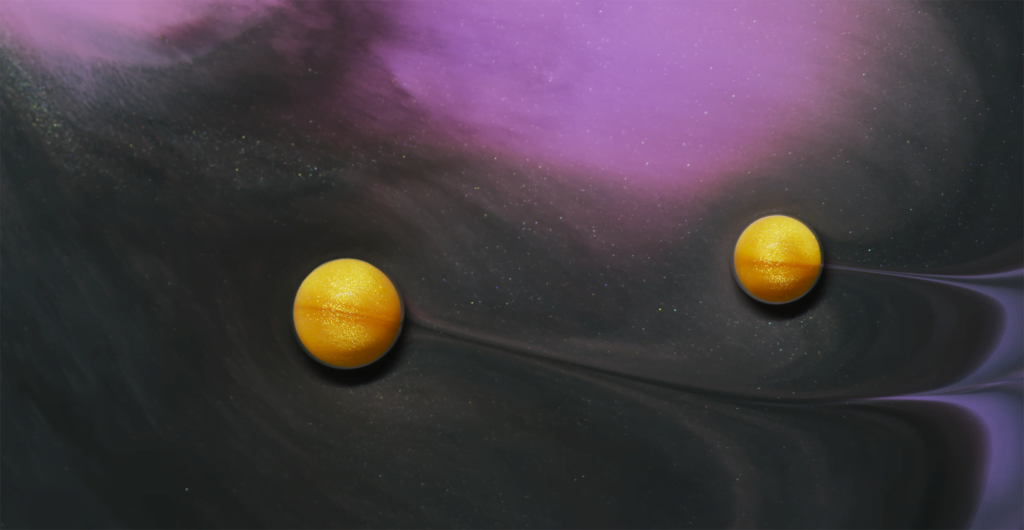

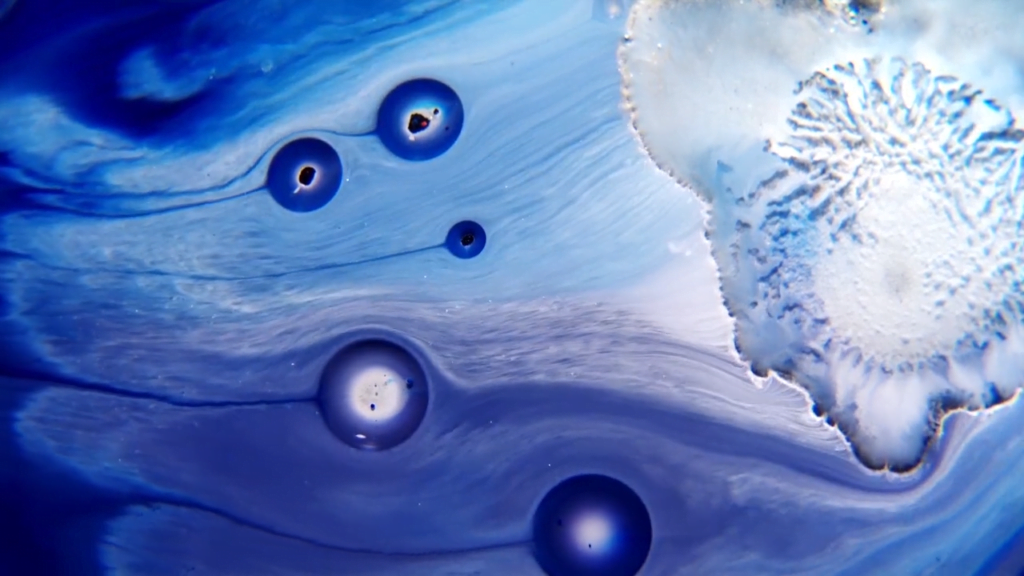

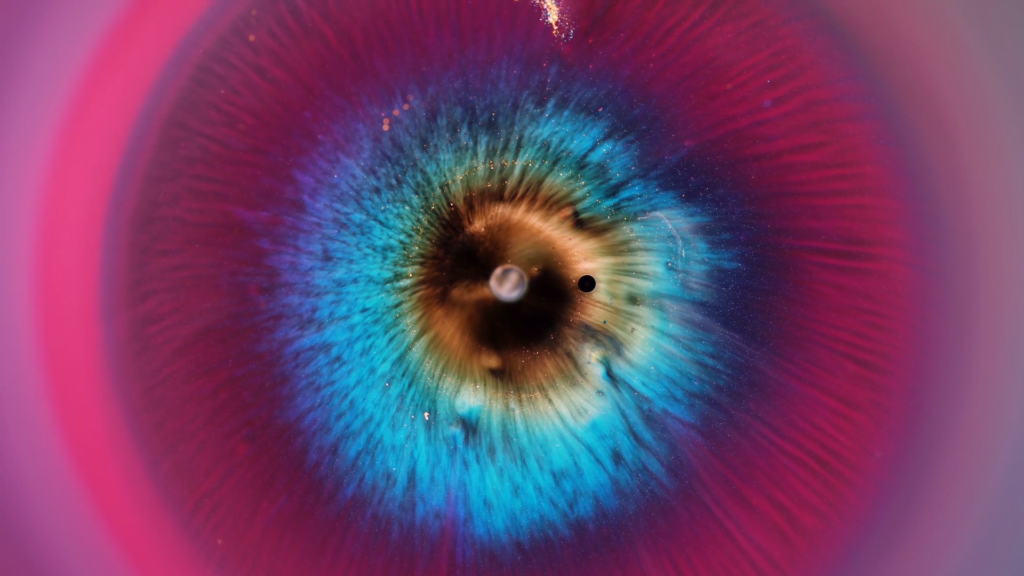

Bursting bubbles enhance our drinks, seed our clouds, and affect our health. Because these bubbles are so small, they’re easily affected by changes at the interface, like surfactants, Marangoni effects, or, as a recent study shows, viscoelasticity.

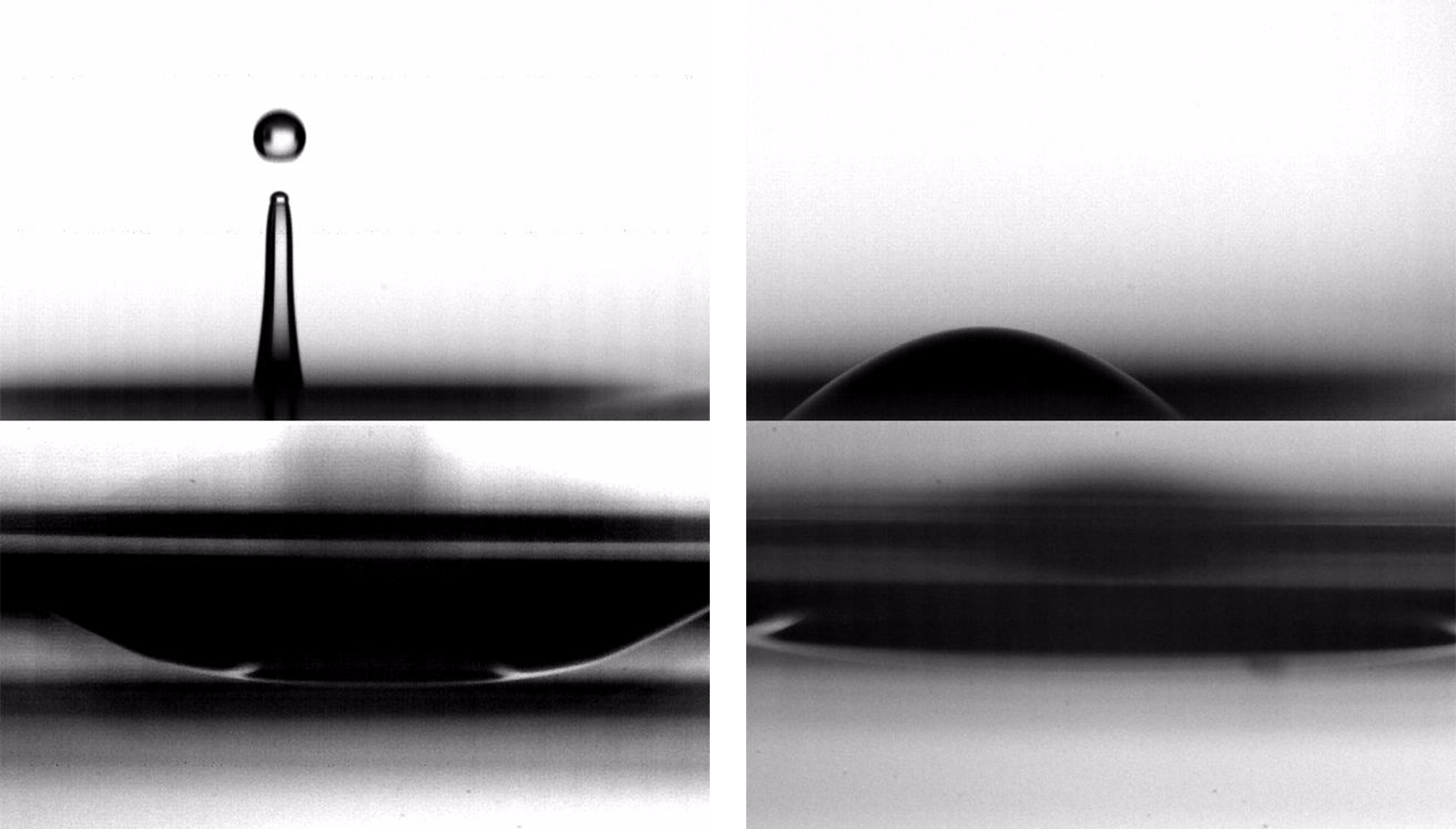

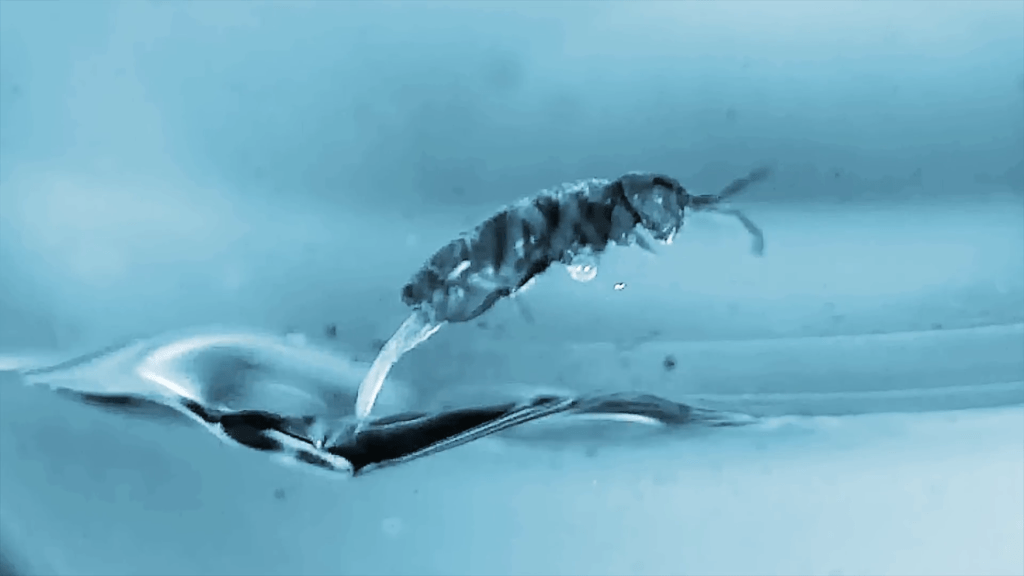

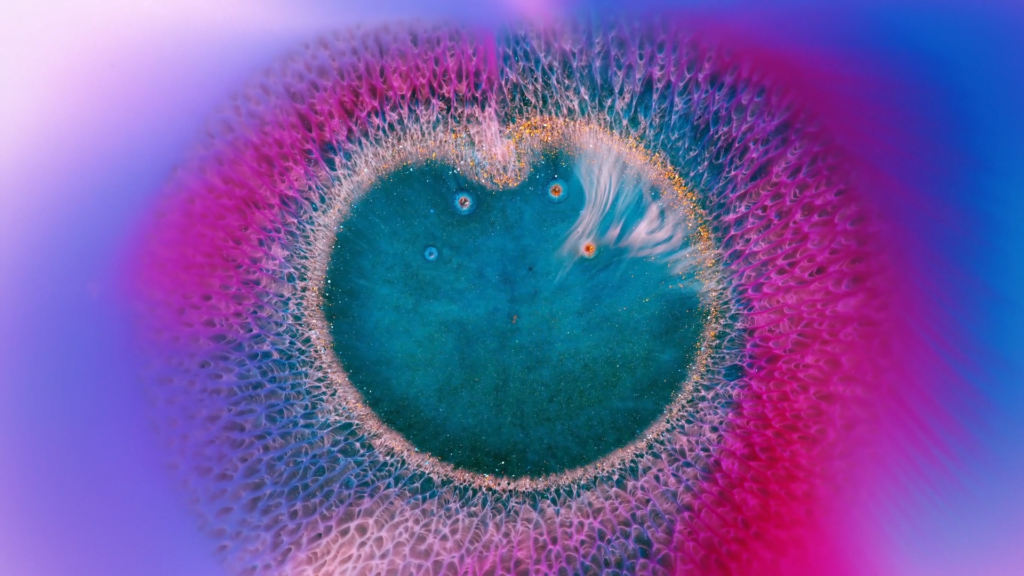

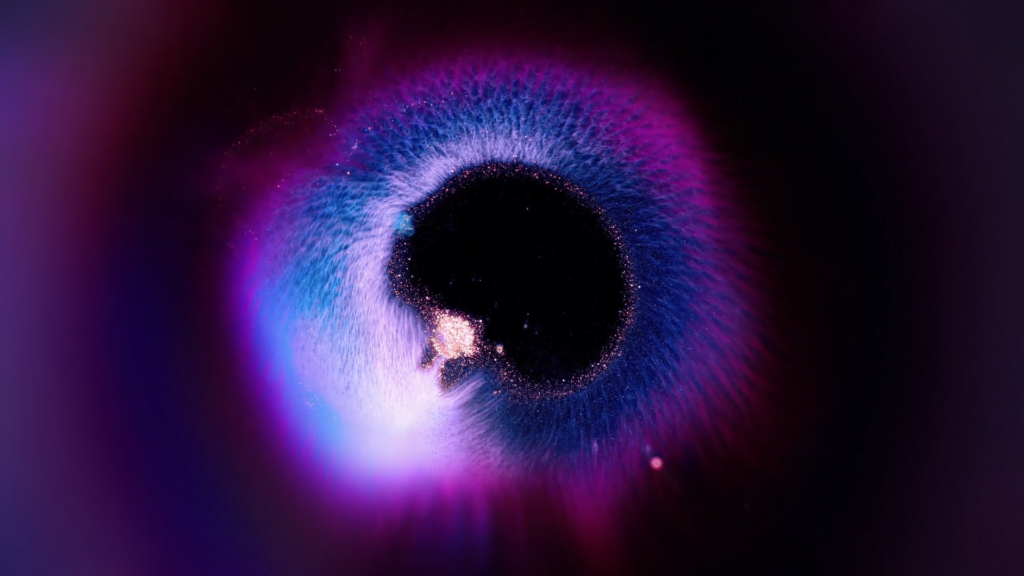

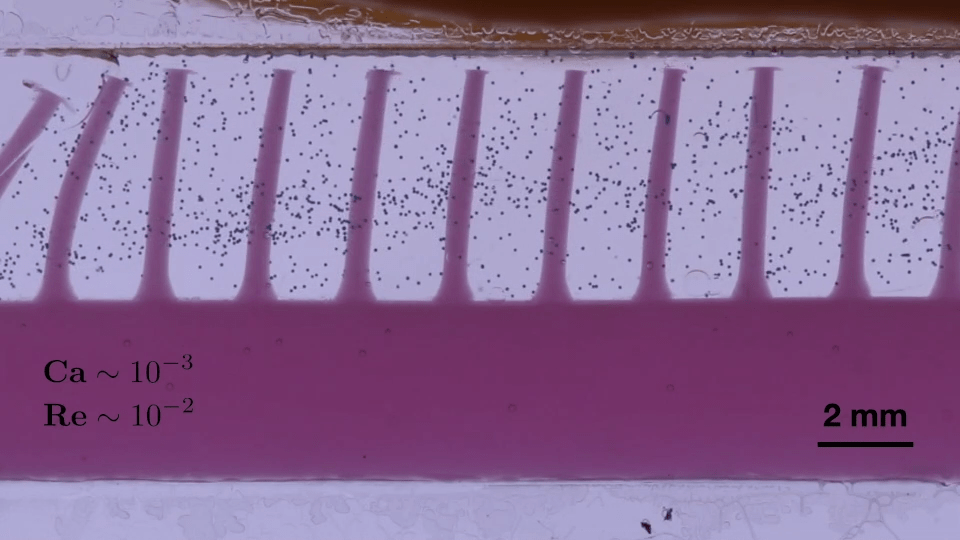

In clean water, a bubble’s burst generates a rebounding jet that shoots off one or more daughter droplets, as seen in the animation above. But when researchers added proteins that modify only the water’s surface, they found something very different. As seen below, the bursting bubble no longer generated a jet, and, instead of forming droplets, it made a single, tiny daughter bubble. The difference, they found, comes from the added viscoelasticity of the surface. The long protein molecules resist getting stretched, which damps out the tiny waves that surface tension usually produces on the collapsing bubble cavity. (Image and research credit: B. Ji et al.; submission by Jie F.)