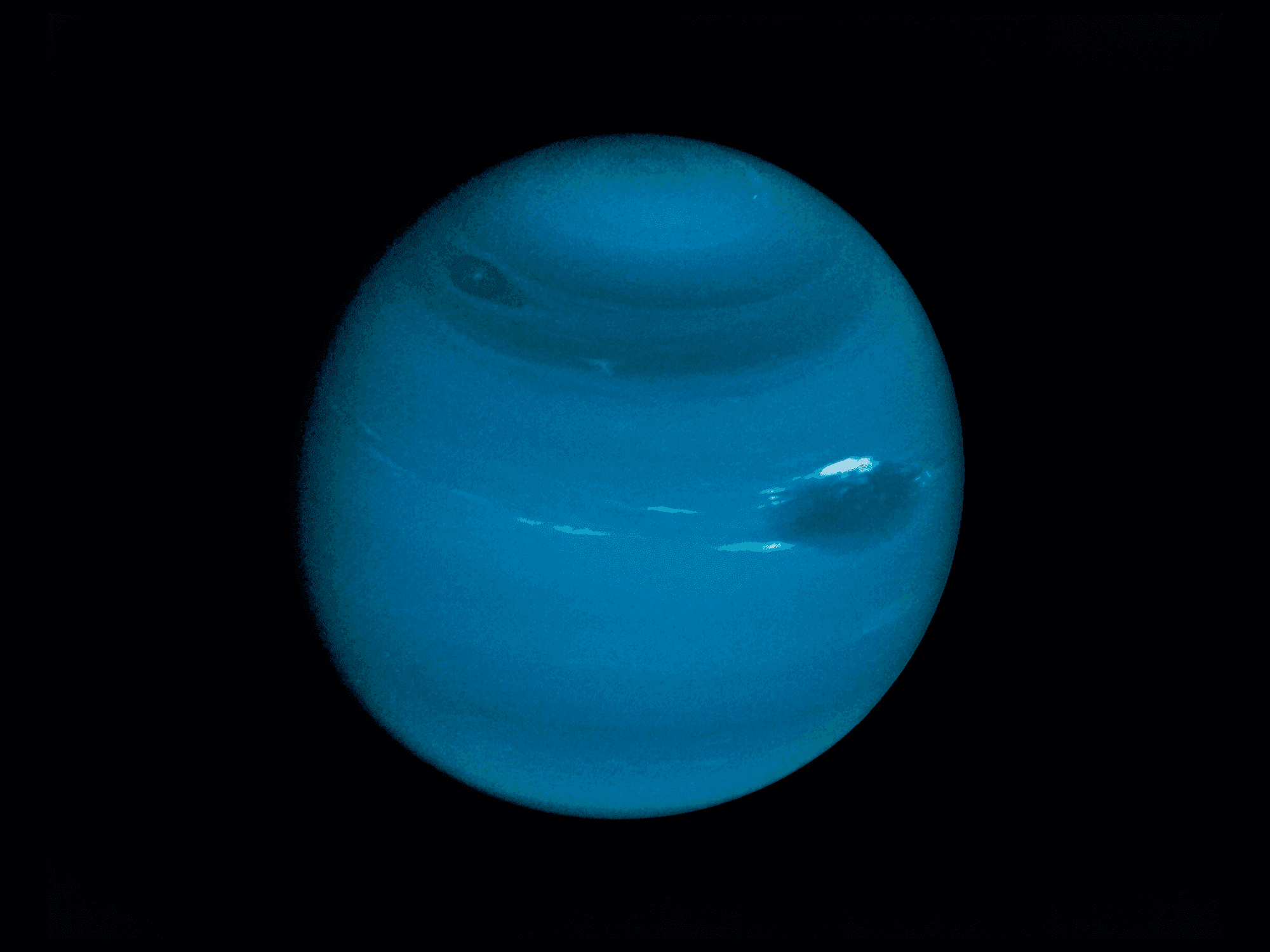

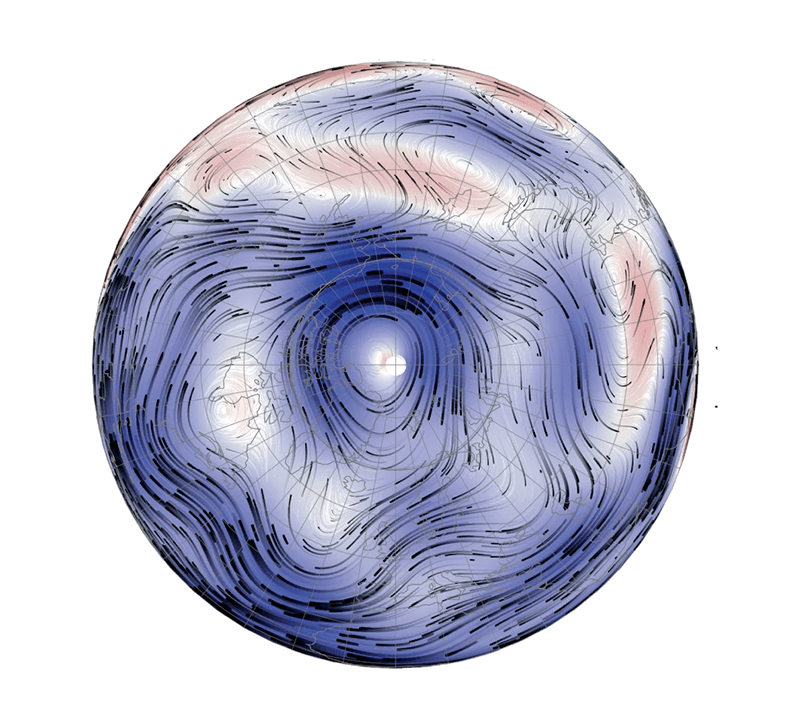

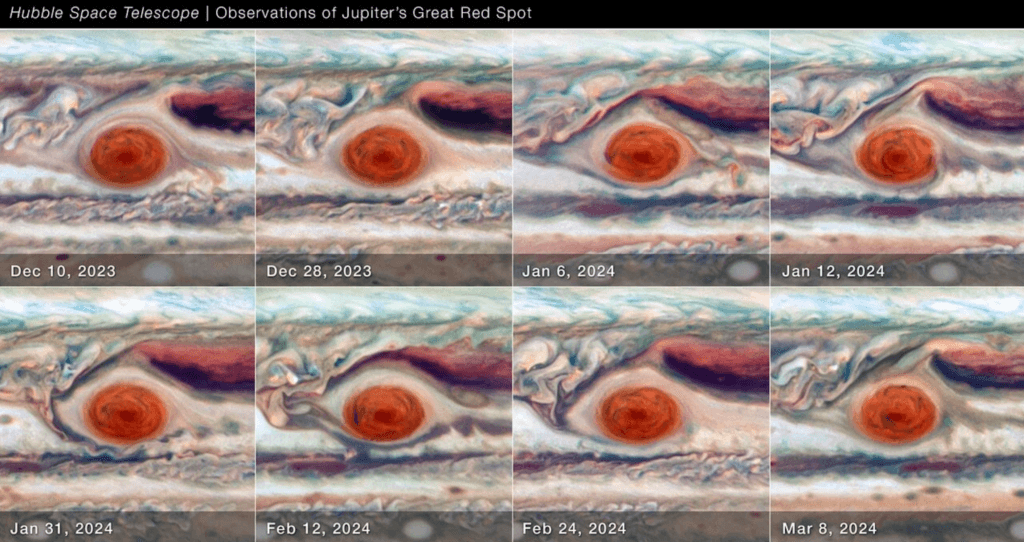

WASP-127b is a hot Jupiter-type exoplanet located about 520 light-years from us. A new study of the planet’s atmosphere reveals a supersonic jet stream whipping around its equatorial region at 9 kilometers per second. For comparison, our Solar System’s fastest winds, on Neptune, are a comparatively paltry 0.5 kilometers per second. The team estimates the speed of sound — which depends on temperature and the atmosphere’s chemical make-up — on WASP-127b as about 3 kilometers per second, far below the measured wind speed. The planet’s poles, in contrast, are much colder and have far lower wind speeds.

Of course, these measurements can only give us a snapshot of what the exoplanet’s atmosphere is like; we don’t have altitude data, for example, to see how the wind speed varies with height. Nevertheless, it shows that exoplanets beyond our planetary system can have some unimaginably wild weather. (Video and image credit: ESO/L. Calçada; research credit: L. Nortmann et al.; via Gizmodo)